Lost Samba – Chapter 03/01- Moving to Bossa Nova Land

The London to Rio de Janeiro flight took two long days, stopping in Lisbon, Dakar and Recife in northeastern Brazil. The modern airports, the glamorous hostesses, the high technology, the generous meals and the feeling of being part of the international jet set, did not compensate for the engines’ hum that left a ringing in one’s ears for days.

On a 1956 dawn, the airplane carrying Raphael and Renée touched-down at Rio de Janeiro’s Galeão Airport. As the cabin crew opened the door, the early-morning tropical air hit the couple and that blissful feeling caressed their skin. Exhausted, but relieved for having arrived and comforted by the pleasant weather outside, they walked down the airplane’s unstable staircase and contemplated the beauty of their surroundings, fantasising about the new life that was about to begin. After months of making plans and arrangements, they had finally arrived in the country they had dreamed of for so long. Inspired by Hollywood big-screen imagery, magazine features and documentaries, Rio seemed to offer everything a European could possibly wish for following two world wars: natural beauty, economic prosperity, good weather, racial harmony and above all the rare attribute of happiness.

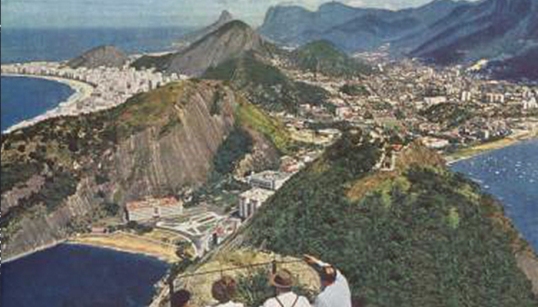

After passing through passport control Raphael and Renée identified their luggage. Although very few people spoke English, the airport was chic and well organized and soon uniformed porters appeared to carry their suitcases to the taxi queue outside the terminal. Inside the car, in very poor Portuguese, they read the paper with the address of the hotel they were going to and waited for the driver to load their cases and go. Looking through the window the penny dropped: it was real! Excitement flooded in, and as the taxi set off they put on their sunglasses and enjoyed the scenery. First they passed alongside the bustling dock area, then they weaved through the city centre with its contrasting mix of colonial-era churches and Belle Époque and modernist-style public buildings. At the end of the green avenue, they reached Guanabara Bay where they would soon see the Sugar Loaf, and from there the cab sped by the gleaming neighbourhoods of Flamengo and Botafogo before finally going through two tunnels to reach Copacabana.

*

From their sunny Copacabana hotel room, the newly arrived couple planned their first mission: to choose a place to live. With a bank account filled with plenty of valued British pounds, this was a pleasurable yet daunting task. There were many wonderful neighbourhoods to pick from: green Gávea by the mountains; trendy Ipanema and its neighbour, Leblon; traditional Cosme Velho, set in a valley amidst the Tijuca forest and the green Jardim Botânico, alongside the park established in the nineteenth century by Joao VI, the exiled king of Portugal and first emperor of Brazil. There were also more secluded areas to consider, such as relaxed and low-key Urca, in the shadow of Sugar Loaf mountain and Santa Teresa, in the hills immediately behind the city centre, where wealthy merchants and aristocrats had once lived, their elegant villas and palatial houses a reminder of Brazil’s imperial past. All these choices were dreamlike for a couple coming from grey London.

Despite all those choices they opted to remain in Copacabana. What this stretch of Rio de Janeiro possessed that the others lacked was the Hollywood glamour that the likes of Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers and Carmen Miranda had introduced to the world. Copacabana had charisma; in some ways it resembled the stylish resorts along France’s Cote d’Azur, with its clean and calm streets and its frenetic beach life. In other ways, the neighbourhood resembled Manhattan, an urban forest of modern concrete towers with shops selling fancy imported novelties, chic nightclubs and streets jammed with the latest car models.

The “Princess of the Sea” had a cosmopolitan buzz like no other neighbourhood in Brazil. The beach itself was amazing: it was four kilometres long and a range of lush hills separated the district from the rest of the city. Facing the neighbourhood, out in the open ocean, a group of small islands covered with wild greenery broke the dullness of the horizon, An elegant promenade, the Avenida Atlantica, bordered the sand; this was the stage where the wealthier cariocas – Rio’s natives – exhibited their toned and tanned bodies during the day and where in the evening they showed off their best clothes when they went for a stroll.

Copacabana was part of Rio de Janeiro’s upmarket Zona Sul, or southern zone. It was there the likes of Vinicius de Moraes, João Gilberto and Tom Jobim gave birth to the bossa nova, that samba-jazz fusion. Although these artists preferred to live by the next beach down the coast – in bohemian, but chic, Ipanema – the swankiest music venues in town were along Copacabana’s Avenida Atlantica, while the coolest places to go were in the alleys behind it, such as the Beco das Garrafas, where the trio and other future bossa nova legends regularly performed. This was the cradle of most of the genre’s classics. None was more famous than “The Girl from Ipanema”, a song that Frank Sinatra would record at the height of his career, and which rivalled in sales anything the Beatles or the Rolling Stones recorded at the same time.

This new laidback style of playing samba was a reflection of a wealthy, self-confident and modernizing Brazil. The president, Juscelino Kubitschek’s, slogan was to build “fifty years in five”. With this mentality, he set out to construct a new and futuristic capital, Brasília, in the sparsely inhabited centre of Brazil, at the same time he invested heavily in infrastructure and opened the economy to foreign capital. The country’s industrialisation accelerated fast and with a widening consumer market, opportunities seemed unlimited. Bossa nova was the musical expression of this optimism – it was clever, urban, mainstream and sophisticated, yet in love with its Brazilian roots.

Although my parents only listened to classical music, they fitted in well with the new middle class who were eager to live according to the international standards as portrayed in foreign movies that fired their imaginations and in the magazines that they devoured. Coming from London, despite the hardships of the post-war, Mum was quick to notice that she could embody the glamour of the developed world, and she welcomed the role of ambassador of that image with conviction and joy. As for the couple’s search for a new home, it did not take long to find a spacious, ocean side penthouse apartment with a veranda and stunning views. The building was on the corner with Avenida Atlantica and, like all others in the area, it resembled a luxury hotel. Marble panels and gigantic gilt-edged mirrors lined its entrance, giving it an air of something similar to a Hollywood set or a European palace.

Their household goods, purchased at London auction houses at post-war bargain prices, included antique furniture, such as an authentic Chippendale side-table, a grand piano, fine English silver, high quality china and classic paintings. Everything had been shipped ahead, and was sitting in customs at the docks.

While Raphael set out to make contact with the people whose names friends had given him, Renée stayed in charge of clearing her treasures. Armed with some basic Portuguese that she had acquired in London in preparation for the move, she set off to deal with the Brazilian bureaucracy. For the custom’s officer, she could not have seemed more of a typical rich gringa. Despite the warnings of her new neighbours and her friends, Mum could hardly imagine that such a charming man in such a responsible position could be fishing for bribes, although everyone had assured her that anyone in such a job would expect an “incentive” to expedite things. On one crucial afternoon, however, her fear of giving offence was so strong that she could not bring herself to hand him an envelope containing a nice sum of cash. This hesitation cost them another four months of waiting.