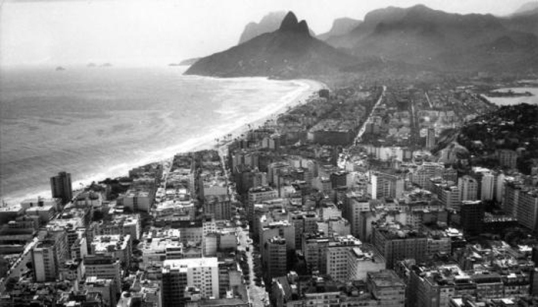

Lost Samba, Chapter 09/02 – Ipanema in the seventies – Brazil’s California.

In 1973 there was a major stock market crash due to the sudden increase in the price of Petrol internationally, and, as anywhere else in the world, people who had made easy fortunes suddenly lost everything from one day to another, leading to a major drop in real estate prices. Dad was either clever or lucky enough to have sold his shares just days before the collapse and for us this stroke was like winning the lottery. Having plenty of cash available, my parents were able to buy an apartment in Ipanema, and to move into Rua Nascimento Silva, only a few doors away from the home of Vinicius de Moraes, the acclaimed Bossa Nova poet.

The new address meant an upgrade not only in our social status but also in our lifestyle. Although the flat did not have a verandah as the rented one in Copacabana, the new home was much larger and, more importantly, it was ours. The previous owners had joined two small three bedroom flats into a single unit. At its centre was the kitchen, which separated my parents’ side of the flat from the one where Sarah and I moved into. Now, each of us had our own room with a privacy that was a dream for most kids.

Regardless of the hurricane of social change going on behind closed doors, with the exception of the beach front Avenida Vieira Souto, in terms of architecture and of environment, Ipanema felt like a luxury version of a typical Brazilian coastal city. The streets were calm, airy and lined with lush trees that almost hid the sky. Its buildings were newer than those in Copacabana but were lower and less ostentatious, giving the district a more residential, down to earth feel.

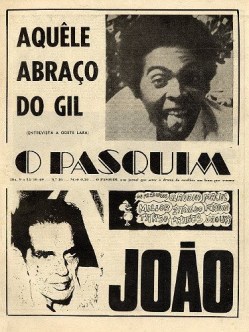

Our new home seemed to bring sudden changes to our lives. To begin with, in what was surely one of the coolest places to live in the entire planet, Sarah and I went from being children to being adolescents, both of us discovering the delights and set backs of that period of life. In second place, my parents finally gave way and bought a television set, perhaps accepting that elegant society considered it strange for their aspirants not to have one. Our new TV immersed us even deeper into the wider Brazilian world. Like anybody else, now we could watch TV Globo’s four different novelas, or soap operas, Brazil’s main cultural product, five days a week. Although I soon got tired of them, in the beginning I was hooked: at six in the evening, there was a novela aimed at youngsters; at seven there was a pre-dinner comedy; at eight there was the big production for the entire family; and at ten, there was a more adult show. All were excellent: censorship had forced the best professionals in the field to work in them, as there was otherwise very little space for independent voices in the entertainment industry. This concentration of talent gave the genre an amazing quality that would help them be hits all over the world.

Due to my Mum’s complete disdain for the medium, she did not want our black-and-white television in the living room but instead it stayed in a spare room next to mine. Every evening at seven Dona Isabel, switched on the set to listen to the soap operas from the kitchen as she prepared dinner and this sound track only ceased when we went to bed. Apart from knowing what went on in the novelas, I could watch football games, sitcoms, films and imported TV series while on Saturday afternoons I could enjoy seeing the latest international bands on Sabado Som. Suddenly I was no longer a complete alien at school.

*

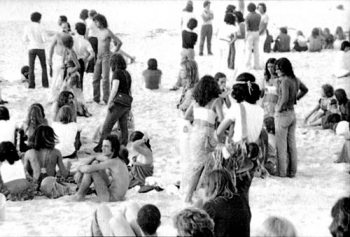

Probably the reason why the previous owners had sold their Ipanema flat to my parents was that the neighbourhood’s main street gang used the building’s entrance as their base. Although they had a middle class background, they were the bad boys at the top of Ipanema’s food chain who ruled not only the streets, but also the waves with their surfing skills in the hippest part of the beach, the Pier. Now long gone, the Pier was set up for the construction of an enormous pipe to funnel Ipanema’s sewage out into the deep ocean. Because its construction had altered the currents and the seabed, the waves there were amazing and the specialised press ranked that particular point as one of the best places to surf in Latin America. These circumstances would make the Pier produce many of Brazil’s first surf champions. Anyway, the gang’s constant presence in our entrance way brought the 1970s rebellion right to our doorstep. Mum and Dad felt besieged by a bunch of barbarians.

One of the gang members, Pepê, was to become a world champion surfer and hang-glider, and years later his popularity would help him be elected into the city council. His younger and less talented brother, Pipi, was shot after he jumped over the counter to attack the owner of the botequim, or bar, on our corner. One day I was coming home from school when I saw a peroxide-blond surfer sitting motionless on the pavement, waiting for an ambulance with his blood-soaked shirt stuck to his belly. The next morning as I was leaving for school, our building’s porter told me that Pipi had died in hospital.

Whenever there were no waves, the gang hung out on the other side of the street to skateboard on a garage ramp while blasting out Deep Purple, Alice Cooper, Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones from a cassette player. While none of them could understand the poignant lyrics, I could, which made me somehow participate in what was going on as I watched them from our living room’s window like a sick boy watching other children play from a hospital ward. In those afternoons, the songs’ words, together with the smell of cannabis wafted into our flat. Seeing the cigar-sized joint passing from hand to hand among the suntanned surfers was like witnessing a bank robbery from a privileged position. This was the subversive crime that the authorities were warning everyone about on television now that the fear of left wing terrorism had died off.

Anytime I passed in front of that gang, I would hear them comment, “There goes that little wimp”. The most embarrassing moments were when we went by car to the club and the porter had to ask those surfers politely to move aside so that our car could exit the garage. As we left the building, inside was my middle-aged mum wearing a white mini-skirt tennis uniform and me with my skinny legs and my oversized football gear. Because of them, my parents ended up banning surfing at home but those guys pushed me to prove, if only to myself, I was not the wimpy kid they saw. I am still trying.

back to chapter 01 next chapter

An extract of the film Garota Dourada shot at the time.