Lost Samba – Chapter 7/1 – A Jewish boy in Rio

I was proud to be one of the chosen for the commando troop to capture the enemy’s flag. Our madrich’s, or instructor’s, plan was to cut through the bush and make a surprise raid to capture the blue team’s flag which stayed under a canopy in the centre of the football field down at the foot of the hill. This would be our tactic to win the simulated war and claim the trophy. To help us, another team would divert our enemy’s attention by staging an attack on the main road. Our group stealthily progressed, weaving our way through enemy lines. Whether through lack of commitment or carelessness, one by one my comrades fell prey to the blue team’s scouts, who “killed” them as they read out the numbers on their arm-tags. This ended up leaving me as the sole survivor. Now alone, I managed to hide and stayed waiting for the right opportunity to advance.

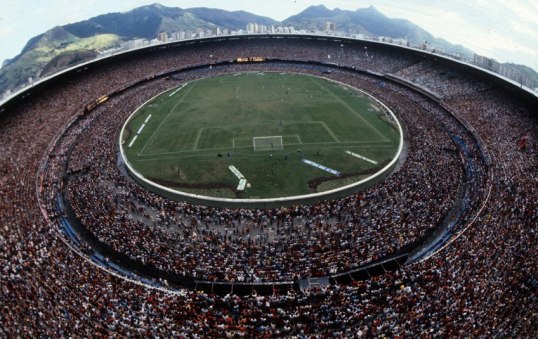

I was proud to be one of the chosen for the commando troop to capture the enemy’s flag. Our madrich’s, or instructor’s, plan was to cut through the bush and make a surprise raid to capture the blue team’s flag which stayed under a canopy in the centre of the football field down at the foot of the hill. This would be our tactic to win the simulated war and claim the trophy. To help us, another team would divert our enemy’s attention by staging an attack on the main road. Our group stealthily progressed, weaving our way through enemy lines. Whether through lack of commitment or carelessness, one by one my comrades fell prey to the blue team’s scouts, who “killed” them as they read out the numbers on their arm-tags. This ended up leaving me as the sole survivor. Now alone, I managed to hide and stayed waiting for the right opportunity to advance.

They were worried. “There is still one hidden in the bush,” shouted an enemy. “He’s there! I can see him!”

But he could not: as a decoy, I was throwing stones, just as I had seen in my favourite war television series, Combat. At one point, their feet passed a few centimetres from my eyes but I managed to creep silently away to the edge of the field, only a short run from the enemy’s flag.

As I waited, one of their number returned from our camp telling everyone that their attack was succeeding. The premature celebration was my opportunity and I went for it. When they noticed what was happening, a mob came running and caught up with me as I was a couple of meters away from the base. As soon as they could touch me, a storm of anonymous arms tried to throw me down and to “kill” me by taking my right hand off the tag around my left arm and reading my number out loud, but I only had two steps to pull them along with my weight and I made it.

I was such an oddball, half a gringo – unknown to most parents, from a different school and from the rich part of town – that no one knew how to react to such an unlikely victor. As for me, I felt as if there was no one to celebrate with.

The exercise was the closing event to a ten-day seminar-cum-holiday camp, or Machaneh, in a countryside resort with the Yiddish name “Kinderland”, organized by the Ichud Habonim, the Zionist organization to which I belonged. To be honest, the ultimate goal of this and the several other available “movements”, as the Jewish community called them, was to convince us that as adults we should move to Israel and serve its army. To do this, they tried to inject us with a strong dose of Jewish nationalism by lecturing on how the Jews – like any other nation – had the right to live in their own land without fearing pogroms, inquisitions, expulsions or holocausts. However, the success rate was low as most parents saw them just as a way of preserving their children’s Jewish identity and dreaded us leaving them, not least because of the possibility of being involved in a war. For us it was just about having fun and making friends, none of us saw the Machanehs as being part of a wider political project. Although no madrich ever brought up basic questions regarding the legitimacy of an exclusive Jewish state in that piece of land or of the fate of the Palestinian people, hate or racism were never on the agenda.

Yes, I am a Jew, and all of my life I have felt in the flesh the contradictions, unexplained myths and pre-conceptions attached to perhaps the strangest people on Earth. It is still not clear if being Jewish means belonging to a nation or belonging to a religion. Regardless of the answer, the induction was a painful one: when I was ten days old, a bearded man in black clothes approached me with a sharp blade, sang something strange and then proceeded to cut off my foreskin without any anaesthetic. The rabbi blessed that snip which was to be my passport into an extended family that, according to the Bible, began some 4,000 years ago with someone called Abraham. The acceptance ceremony also meant that my penis was to look different to the ones of my football mates, that I was obliged to sit through religious services in a language that few in the congregation understood and that I was to observe holidays that none of my school friends observed while pretending to ignore their own holidays.

At home, my parents considered being Jewish good; their family and their friends too – after all, that is what we were. However, in the wider world, not everyone seemed to agree. When I was about five, I accidentally opened a big book about the Holocaust. I could not read but I could understand the pictures of religious Jews crying moments before the Nazis murdered them, of soldiers threatening children with machine guns, of skeletal people with expressionless faces in striped pyjamas behind barbed wire, and of piles of corps in mass graves. Their only crime was to have been as Jewish as I was. In the community, the experience was a recent wound, and it lived on in locked up internal repositories of pain. The grown-ups seldom spoke about their ordeals, we only knew about them by hear say though we could sense something deep and heavy through their unspoken fears and their mistrust of non-Jews.

On the other hand, in a Latin American country ruled by a dictatorship, Roman Catholicism was a strong presence in everyday life. Even in the sport so dear to my identity, the heroes of my team and of the national squad made the sign of the cross every time they scored while my favourite football commentators used a lot of religious exclamations. Apart from this, in every day life, Christian imagery and expressions came out in most conversations. At the British School, due to the Church of England link, things were slightly different. My friends both at school and at the club were mostly Protestant and, as the only Jewish boy who played with them, they considered me as somehow different from the stereotype Jew. This made them feel comfortable to tell me strange things they had learned at home about my people, comments that I could not agree with. Based on my personal experiences, I knew that we were neither stingy nor evil plotters bent on world dominance and I had never come across anyone drinking the blood of Christian children during Passover or, for that matter, at any other time of the year.

As boys do, I wanted to be part of the group, and although I pretended to accept what my friends said, in my heart I knew that there was something fundamentally wrong in my being forced to be a closet Jew. Living amongst the “goyim”, I felt an affinity with Moses growing up in the Pharaoh’s court and sometimes wondered where this was going to end. One issue that intrigued me was that my Christian friends had a human respect and a sense of brotherhood that I never found with my Jewish ones. It never crossed my mind that this goodwill derived from their religious commandment to love one another, neither did I know that this love could be selective and that one or two generations back this duty would never have encompassed “non-believers” such as me.

The one thing that I knew for sure, was that belonging to God’s “Chosen People” was strange. Membership of this select group had nothing to do with personal choice and being Jewish had too much weight in every aspect related to it. The very word “Jewish” would turn people away or produce smiles without any logical reason, depending on who heard it and who spoke it.

Jewish culture had flourished during the Muslim rule of the Iberian Peninsula. The Portuguese had only recently reclaimed their country to Christianity when they landed in the New World, which in many ways made Brazil have close connections with my tribe. The Portuguese kings adopted a brand of Catholicism emphasising the Holy Spirit, preaching paradise on Earth through the universal understanding among men, they saw people beyond their beliefs and therefore turned a blind eye towards infidels. Their system of belief was far less dogmatic than the one of their Spanish rivals, and ended up producing a more accepting and a far less ruthless spirit, at least in relation to Jews. When the Vatican tightened its control over the Christian world and forced the Portuguese monarchy to fall in line and to turn up the pressure, they went to great pains to convince Jews to convert. Many of them did, but maintained Jewish rituals in private while outwardly accepting Catholicism. A large number of these “New Christians” found refuge in the tropics. Many of today’s most common Brazilian surnames referring to trees, metals and animals, such as “Silva”, “Leitão” (piglet), “Figueiredo” (fig orchard), “Pereira” (pear tree), “Nogueira” (walnut tree) and so many others descend from them.

Dad and his friends were part of the most recent wave of immigrants of the Jewish faith to arrive in Brazil. They came because of the war and most considered themselves as temporary residents who were waiting for a United States residency permit. The ones who decided to remain in Brazil were part of just another group of people flocking in. Japanese, Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, Italians, Germans and Lebanese also arrived seeking a share of Brazil’s newfound prosperity. The long haired, reinforced concrete Jew blessing Rio from a vantage point in the Tijuca forest welcomed his patricians and all the other foreigners with open arms.

For most cariocas, our people were a welcome novelty. Behind the wall of prejudice, they discovered thinkers who carried with them sophisticated and cosmopolitan European cultural baggages. In business, most people recognized Jews – or the majority of them – for their strong working ethos and high moral standards. In general, they passed unnoticed in a society defined by its ethnic and racial diversity and many rose to positions of prominence. This was to be the case for my cousin, Bibi Vogel, for the Israeli born actress, Dina Sfat, for the writer, Clarisse Lispector, for the mega-popular television presenter and media mogul, Silvio Santos, for the tropicalista poet, thinker and composer, Jorge Mautner, and for the humorist, Bussunda, to name but a few.