Lost Samba Chapter 08/01 – Brazilian social inequality under the microscope.

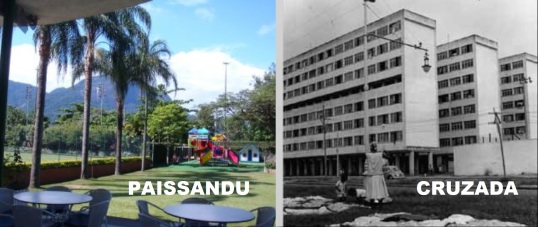

The Clube de Regatas do Flamengo was one of several of upper middle class clubs clustered next to some of Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The Flamengo club, home to the world-famous football team of the same name, was on the shores of the filthy waters of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas (Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon), near our own Clube Paissandu as well as near to the Clube dos Caiçaras, the Clube Monte Líbano, the Associação Atlética Banco do Brasil, the Clube Piraquê, the Clube Militar, the Jockey Club and the Equestrian Club, or, as it was usually called, the Hípica.The Flamengo’s grounds were the largest of all the clubs and it was the easiest to join. Perhaps because of its size, the Flamengo was the only one to have proper sports facilities including an Olympic-sized pool, where some of Brazil’s top swimmers practiced, and where I took lessons three times a week.

After the swimming classes, I would walk to the Paissandu down the block. Despite being so close, everyone considered the walk dangerous as although this was a major route for cars, there were no shops, houses, offices, or street life, only tall concrete walls protecting the clubs. Because of this, the area was a fertile ground for assaltos, or muggings. One afternoon three favelado boys approached me, asked what I had in my bag, threw me to the ground and then ran off with my belongings. There was nothing of value – just a wet towel and my trunks – but the feeling of impotence for not being strong or courageous enough to react was traumatic. I was only twelve and when I arrived at the club house in tears, Mum’s British instinct set in and we immediately went to the local police delegacia to file a complaint. The delegacia was across the street from the Paissandu Club. The bored receptionist took us upstairs to talk to the delegado who did not even bother to move from behind his heavy metal desk. The fat, dark, moustachioed commander barely glanced at us through his sun glasses, tossing towards us some mug shots of dangerous criminals to see if I could recognize any.

The station was a yellow bunker-like construction with thick bars on its windows and had all sorts of police cars parked around it and had the insignia of Rio de Janeiro’s military police plastered over the door to make everyone take notice of the menacing importance of the building. The Fourteenth Delegacia de Polícia faced the Cruzada São Sebastião, a narrow alley that hosted the only social housing in the neighbourhood. This was by far the most dangerous place in the otherwise exclusive Ipanema and Leblon districts, somewhere we had always be warned was a complete no-go area. In fact, the Cruzada was very much like a refugee camp, its residents being the remnants of Praia do Pinto favela that until the 1960s had existed in the midst of all those exclusive clubs. Shortly after the 1964 coup, the military authorities backed its burning down after several “peaceful” attempts to remove the inhabitants. The land was conveniently freed up for friendly building contractors, and the families who then moved in were mostly of the military’s middle ranks.

The people lived on one side of the Cruzada São Sebastião in prison-like rows of eight-storey buildings. On the other side of the alley there was a tall wall, topped by a fence covered in barbed wire, which separated that silently angry enclave from our five-a-side football field. We often played at the same time as the boys on the other side of the wall. If our balls flew over, they would never come back. The same was true for their balls but, as they were better players, few landed on our side. There were occasional exchanges of rude words and stones, and sometimes more daring kids climbed up to threaten us but, in so doing, they then became easy targets for ball kicks.

Boys like those from across the alley and like my muggers worked in our club as tennis ball boys, their parents sometimes being part of the club’s under paid staff. Without exception those moleques were miles tougher and fitter than even the toughest and the fittest of us. Occasionally, we would play against them but we might as well have sat back and learned something from their genuine Brazilian footballing magic.

We feared them but, at the same time, we also secretly respected them. The truth is that every carioca male was a bit jealous of the archetypal black man, admired for being good at football, fighting and samba idealized as being supremely virile and with tons of sexy women running after him. The only desirable feature that they lacked was, of course, our white skin.

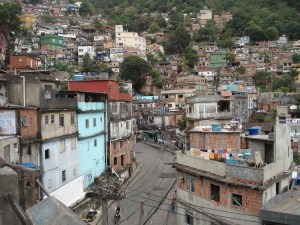

The people who we classified as favelados were the great proportion of Rio’s population, but they only emerged into our field of vision and respect either as football stars, as artists or, for some of us, as drug dealers. Otherwise, as far as we were concerned dark and poor people were servants and maids in our homes, clubs, schools and office buildings. Outside work, they were carnival dancers, beggars and muggers, people waiting to be put in prison and deserving their fate for being lazy, dishonest and libidinous. Ultimately, with the backing of the middle and upper classes, Rio’s undemocratic administration was working hard to keep the masses as far from us as possible. For them, people who had committed the crime of being born with dark skin and poor were to be no more than extras in our closeted existence, similar to how South Africa’s non-white population lived under apartheid.

In our homes, the link between the rich and poor world was embodied in our maids. Those female servants, and the attitudes to them, were remnants of the days of slavery, which in Brazil only ended in 1888 – not even seventy-five years before I was born. Every flat or house built for the lower middle class upwards had a servants’ quarters, and we all had at least one maid at home to clean, do the laundry and cook. They would labour all week doing long hours, and sleep in stuffy, windowless rooms with the sole comforts being a crucifix on the wall and a cheap radio set on top of a small cupboard. Outside their door, ironing boards, brooms and dirty clothes waited for them. The contrast with the rest of the comfortable homes where white Brazilian middle class families enjoyed their tropical paradise was staggering. This almost unnoticed element of the social gap was a constant in daily life no matter the head of the family’s profession, religious belief or political views. Leftists were no exception; their political fantasies did not inconveniently interfere with their domestic comfort. They viewed “the proletariat” as “noble savages” who they liked to imagine lived in a permanent samba party and were inherently good, just as all exploited members of the underclass surely were. But somehow the maids were just too real to be idealised, although – depending on their disposition and looks – plenty of patronizing chatter went on, as well as occasional flirtation and sexual contact.

When I was little, one of the many domesticas who passed through our lives risked her job by secretly bringing her son with her to live in the flat in weekdays. As the rigid code of conduct was concerned, this was beyond the pale. Naturally I knew nothing about such rules and I was the only one at home aware of my hidden friend who followed me everywhere but who hid behind curtains when my mum was at home. One day Mum discovered what had been going on. There was no question of tolerance: Mum fired the maid on the spot. This harsh attitude was in line with the ethics of that time and place, and it went without saying that all our neighbours and friends supported her decision.

In contrast, our last maid, Dona Isabel, stayed with us for over fifteen years. She was a Brazilian version of Mrs Two Shoes, the Tom and Jerry cartoon maid – she was pitch black, short and stocky, and had a gigantic backside above her thick and bent legs. It was common in Brazilian homes for emotional ties with the maid to develop, and certainly this was the case with Dona Isabel: my sister Sarah and I regarded her almost as family. Even so, the general acceptance of the status quo never allowed us to imagine what was passing through Dona Isabel’s mind. We will never know. All we really knew about her background was that she had grown up on a farm in the state of Minas Gerais and had a very typical accent from there, and that she found comfort in Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion. Dona Isabel was barely literate but really smart and she managed to teach herself to understand English .