Lost Samba – Chapter 31/02 – Rock from Rio in the Eighties.

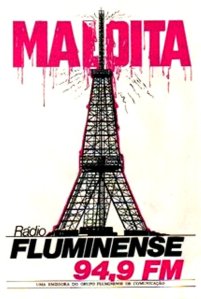

Rock and Roll took Rio over by storm. Everyone seemed to have a band, and those who did not wanted to be involved in one way or another. In the middle of this revolution, someone inherited a Radio station in Niteroi and transformed it into the first pure Rock station in town, Radio Flumnense. Now, no one needed to buy records any more to listen to Led Zeppelin, Yes, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, the Who, etc… This bonanza was short lived as they were approached by the big record companies demanding royalties. Unable to pay, they resorted to playing exclusively 80’s stuff; despite losing their pirate station aura they became avant-garde and introduced Rio’s youth to what was happening in the local and international rock scene.

Michel, a future work colleague, was an international air steward at the time; during his time off in London and in New York he would buy the latest releases of the latest bands and would deliver them freshly to the station. As these bands were from independent labels and had never been heard in Brazil, they were less of a problem to broadcast. No other station aired that kind of music and playing in their station became the passport to success for all the local bands. Arrepio included, did everything they could for them to play our songs. Radio Fluminense was to be the soundtrack of the eighties and was a phenomenon that will never be repeated.

Charles, the studio owner, started getting us gigs, and with the little money we got from them we started investing in demo tapes in order to who knows, finally get some air space in Radio Fluminense. This lead us to better recording studios where we came across impatient sound engineers despising us behind the glass windows. This new phase made us more aware of what we played and taught us a lot. But in a way the pseudo professionalism in those studios got in the way of us getting the best results. The tracks were recorded separately which made those sessions very different to what we were used to; sometimes the musician would get his part wrong or sometimes the engineer messed up and there were endless repetitions where the essence of the band dissipated into technical details.

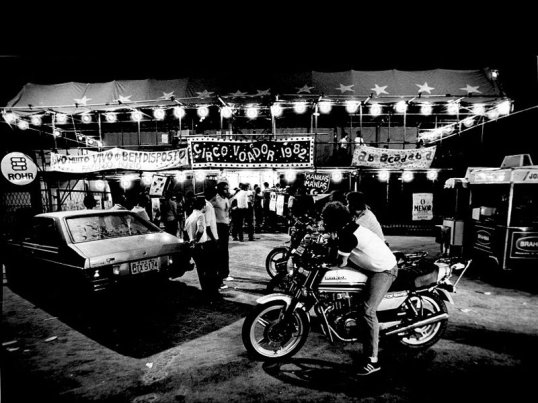

Felipe joined the band through a Posto Nove bump in too. Although he was not attached to the Circo Voador he had become a professional actor with an important role in the play “The Twelve Works of Hercules”, that was to be the cradle of many successful careers in the Brazilian acting world. He was dying to be a lead singer in a band and therefore we had an easy job to convince him to become ours. His voice was good, his presence was superb and with him we gained a new dimension; also, his contacts could break us into circles that could make it happen.

The next step was to do his début gig. Through his connections Felipe arranged one in a bar in Ipanema. It was going to the venue’s first Rock gig after decades of quiet nights of Bossa Nova. We set up our gear in the patio with the staff regarding us as barbarians coming in from the steppes; there was no pre-amplifier or sound engineer; just our instruments, borrowed microphones and the power of Charle’s amplifiers. After we had done the sound check in the afternoon he manager came up to greet us. He was apprehensive about the volume and asked us if we could play lower but we answered that because the drums were naturally loud everyone had to be at a similar level.

At night the guests started appearing; as Felipe was doing a minor role in a soap opera at TV Globo there were one or two famous faces and many desirable future starlets appearing in the room. When the hall filled up, we started. In the middle of the second number, I heard a noise in my ear and when I looked around the manager was shouting that we were too loud. I told him again that we could not play lower because of the drums. He went down and after two numbers, he knocked on my shoulder again and told me that there was someone downstairs wanting to talk to me. I replied that I could not talk then. The next thing we saw were six police officers coming up the staircase, taking the plug out of the wall and killing the gig.

The Felipe days were short lived; he signed a contract for a big role in a TV series and gave up his musical career. I went back to the vocals but arguments started to break out, the rest of the band was more concerned about their technique than my over-confident self; Marcos and Melo were still taking private lessons, which for me was very un-rock and-rollish and they did not want to understand that I couldn’t do the same for financial reasons. On the other hand, I took the venture more seriously; I believed that if we found a sound to set us apart from the other bands we could make it big and I was prepared to invest all of my energies. Meanwhile the other guys took the band with a pinch of salt and regarded the band as a fun weekend activity.

*

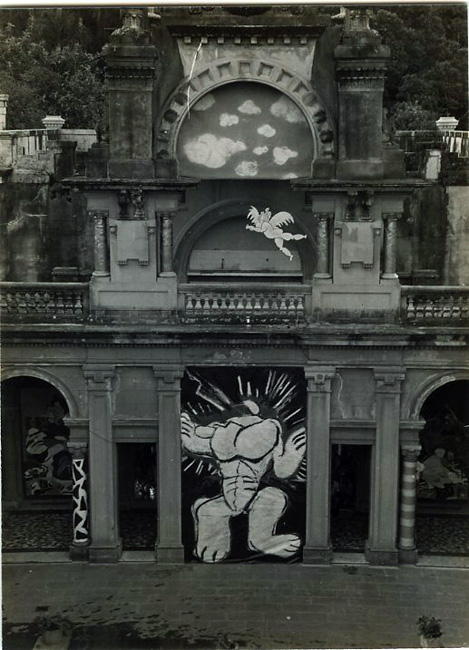

The temple for goths, new romantics, quasi-punks, and other alien creatures was a night club in Copacabana, called Crepúsculo de Cubatão. The name paid homage to Cubatão, an industrial town on the coast of São Paulo state considered the most polluted place in Latin America. It was owned by Ronald Biggs, the famous British train robber, and had everything one would expect from an early eighties venue: the neo-gothic expensive futuristic look with classical overtones, girls and boys dressed up as vampires, a lot of exaggerated make up and no smell of cannabis or hint of heterosexual sex in the air. The ever-crowded door was controlled by a tiny Goth girl protected by two gigantic and un-trendy bouncers. She chose whom she would not let in by pointing at them and pronouncing the death sentence: “she/he looks like a nice guy/girl”.

Strange people started to appear in our lives talking about Post-Modernism and Nietzsche without understanding much of what they were talking about but causing a knowledgeable impression. London had become the new Jerusalem and the British magazines iD and The Face were the new Bibles; in some quarters having a sun tan was seen as a sign of belonging to the Neanderthal age. The irony about the obsession with the London standard was that coming from a semi-British background, I could have prospered big time but I stuck to my coherence and in my mind I was a defeated revolutionary who had stoically not sold out.

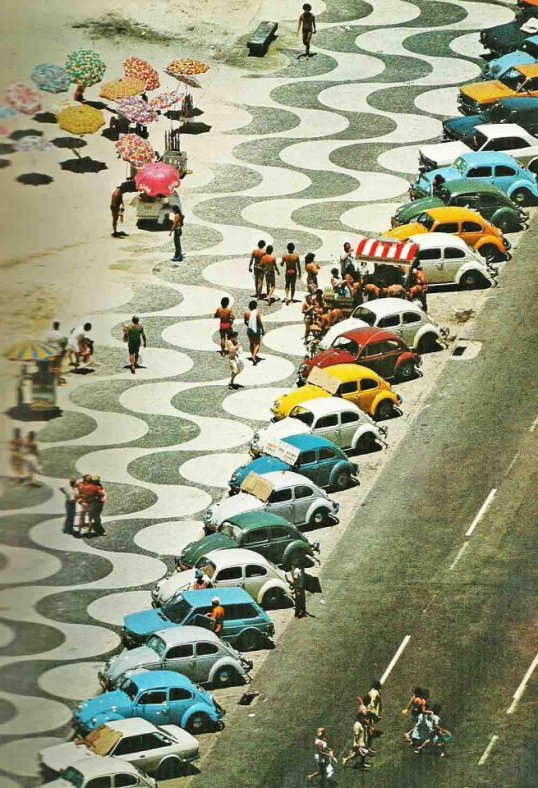

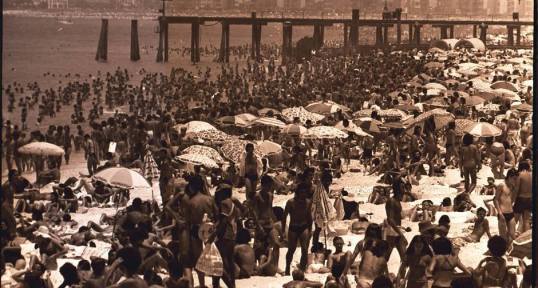

There was a fundamental absurdity in what was going on that I could not come to grips with: Rio de Janeiro’s natural settings did not combine with urban themes. The shallowness of the discussions about visual trends in foreign magazines and which bands and artists were free from the seventies aura had nothing to do neither with Rio’s eternal wildness nor with what I thought or intended to be. On the lighter side, it was amusing to see goths and punks walking around in black leather jackets and boots on 40 degree centigrade sunny weekends while everyone else was in their bikinis or trunks going and coming back from the beach. They looked like vampires in search of morgues to shelter in until night when they could come out and take over the city.

The Carioca middle class punks’ were another case of absurdity; the clothes they wore and the places they had to be seen were expensive and had nothing to do with Johnny Rotten screaming “no future” in London between one spit and another. The punk movement was much closer to the people crammed in buses in Sao Paulo’s outskirts and to people like me being sliced up by the economic lawnmower. We were being kicked in the face by a system that had promised a rosier world as we grew up. There was a lot of right wing talk going on about the survival of the fittest but what we saw was the survival of the ones with richer parents.