Lost Sambista

A Brazil never seen.

Archive for the month “February, 2014”

Lost Samba – Chapter 21/02 – An introduction to Brazilian Psychedelia.

On the day of the exam, I woke up at dawn. Unable to return to sleep, I went for a walk by the beach to calm down. The sunrise was spectacular and the temperature of the water was perfect, the sea was calm and inviting, so I went for a long swim, did some body surfing and managed to relax. As I emerged from the water, I noticed a man on the promenade looking at me. He was dressed in a white suit, tall with a short moustache and an old-fashioned haircut, all of which made him look like my maternal grandfather. This bizarre encounter sent shivers up my spine, but I took the incident as a good omen.

I went home, showered, had breakfast, got on the bus and was soon with hundreds of other students gathered in front of a rundown public primary school at the end of Leblon. After a 10 minute wait, officials dressed in lab coats opened the gates to allow us in and we had to find which classroom we had to go to on a board in the corridor. I took my place at a school chair with an arm that folded down to serve as a table, under which were studded old bits of chewing gum. As we sat down, the invigilators, all in their mid-twenties, handed out pencils and erasers. When everyone was in, the inspectors ran through a roll call and made us aware of the rules: no cheating, no noise, no talking and when they said the time was over, it was over. After this they handed out thick, A4-sized envelopes containing the test booklets and a card on which we had to tick the correct answers.

The exams were spread across four days. I will confess that on the physics and chemistry tests, I had some key formulae scribbled on the lower parts of my trousers, but on the other tests, maths, languages, history, biology and geography, I played clean.

*

Fearing the worst, on the weekend that the results were to be announced in the newspapers, Kristoff and I fled to Mauá. We camped near Maromba and the only link to the outside world was a payphone in a bed and breakfast. Calling Sarah would be the safest way to hear the news: she had gone through the same process before and would not be too judgmental if I had failed.

She had already looked up my name and, to everyone’s absolute surprise, I had been accepted by UFRJ, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, for their prestigious economics programme, considered the best of its kind in Rio as well as one of the best in the country.

Sarah had also looked up Kristoff’s name and gave the news that he would be studying biology at the same university, one of the hardest programmes to get into, with a ratio of 20 applicants for each place. Both of us were over the moon and were ready to celebrate. For the big occasion, we were going to try the latest wise guy, fun hallucinogenic craze: magic mushrooms. Mauá was renowned for them and the weather was just right for their sprouting: sunny, following a few days of steady rain.

We rushed to the closest pastures, but didn’t find any. Our hopes were re-ignited when someone told us that we would surely find them in the pastures of Campo Alegre (the appropriately named “Happy Field”), a village 40 kilometers away. The problem was that we had no means of transport other than our feet, but we were obstinate enough to go on an entire day’s trek to get our golden fungi.

The exhausting walk paid off: we found a field full of them and picked what we could under the menacing watch of the bull who owned the territory. We had to be careful: there were two similar-looking species of wild mushrooms: the desired kind had black stripes on its lower side and a poisonous variety exactly the same but with white stripes. After a moment of elation, we returned to our senses and remembered it would soon be dark and that we faced another long walk back.

Back in the camping site, we took a well-earned plunge in the river, changed our clothes and got the guitars for the night jam. Once we were all set, we ate the mushrooms, wondering what we would experience and when. Their taste was similar to ordinary cultivated mushrooms – they were just bigger and looked more distinct. Night had already fallen when we hit the road and we were lucky to get a lift shortly after. In the back seat, looking out of the window, I started to feel light headed, by the time the car dropped us off and its lights had moved away, we were already on psychedelic ground.

Our lift had let us off in Maromba’s square; a patch of earth defined by the few houses and the church bordering it. In order not to go out on an uncontrollable tangent, we had the good sense to go to the only bar in the village that also faced square. The only other lights came from the grocery store on the opposite side of that unpaved terrain. Locals would gather there because they sold cheap liquor and there was pool table, while the hippies would congregate where we were. Each group respected the other’s space. One group would be stoned out of their minds while the other one was equally spaced out on a deadly mix of the region’s famous honey with cachaça.

As we tried to absorb what was going on, we noticed that there were already two guys sitting at the table and strumming something. We asked if we could tune our guitars to theirs and join in. After some time, a friend who would go on to become a famous guitarist turned up and joined in too. More people started to arrive and the end, there must have been some seven or eight musicians capturing what the spirits had to say about the beauty of the surrounding moonlit mountains and the stars above.

That session was one of the best in my life. An euphoric crowd gathered and participated using whatever means they could to heighten the energy – taking the lead by singing out loud improvised verses, clapping, drumming on tables and on the bar’s fragile walls or simply dancing. Music, place and people merged into a collective trance that endured for hours.

I cannot remember how that explosion of psychedelia ended, nor where I slept, but in the morning, when we went for our daily shot of milk – drawn manually from cows while we waited – everyone was commenting on how good the jam session had been. It turned out that all the musicians had taken magic mushrooms, but had been unaware that the others had done the same. We spent the rest of the day washing off our hangovers at a natural water slide, hurtling into the icy, fresh, water, bringing us crashing back to ordinary life.

Lost Samba – Chapter 21/01 – Sex, Drugs, and Gafieiras in the 70’s

On the serious side, the exams that were going to determine our futures and label our value to society were around the corner and, like everybody else, I was nervous. This rite of passage bothered those of us in Colégio Andrews’ smoky squadron. We questioned what all of that was about and where we were all heading. As Pink Floyd put it, this was our “welcome to the machine”, a money making structure overseeing the way the world functioned, craving for productivity and with an enormous appetite for devouring souls. Above all, we did not want to become elite trained animals, new blood in that circus where everyone and everything was bound to a cycle of working hard to obtain things that they did not really need, but that were presented as fundamental. No one bought the maxim “arbeit macht frei” – work makes freedom – written on Auschwitz’ gates but hammered into our heads with different wordings by our parents, our teachers and other authorities who were already trapped in. They were by no means Nazis, but nevertheless they believed that the only way to escape the inherent injustice of the world was to work hard in order to become a valuable part of the capitalist engine. Like in vampire stories, the moment we became “one of them” there would be no possibility for real happiness, the best we could achieve would be to conform and be content zombies, doing the same as tens of generations before ours did.

No one could deny that we were spoilt kids and that our point of view came from a comfortable upbringing. However, mirroring the perceptions in similar elite enclaves throughout the world, as we detached ourselves from our sheltered but privileged standpoints in society, like paparazzi spotting a celebrity in a surprisingly unfavourable angle, circumstances allowed us to have a clear glimpse of the machine that moved the world, and what we saw was not pretty. There was not much to be done to stop it and there was nowhere and no one to run to, not even to our parents, as they were part of that mechanism. Their rosy view was that the world was experiencing the aftermath of a victory of good against evil where the democratic and socialist forces had crushed Nazism, a hard earned victory that had given hope to the world. For them, despite the unjustified opposition of communist totalitarianism, an explosion of wealth and awareness was bathing the planet and taking it to a better place.

In the minds of the older generations we would be responsible for maintaining what they had achieved through blood, sweat and tears. This post war optimism made most people believe that humanity had achieved something good; a feeling that empowered people to try to fight to improve the world even further. This way of thinking opened a portal of ideals about universal goodwill and freedom that appeared in songs, films, books and all other forms of art and culture. Like Hamelyn’s flute player, these expressions seduced baby boomers and post baby boomers out of a graceless world inhabited by the sour generations that had come before and who had created wars, dictatorships, persecution and so many other horrible things.

However, in many quarters of Latin America the perception of the west’s triumph was not quite like this. After the Cubans had gone too far in their pursuit of freedom, the hand break was pulled and right wing dictatorships had popped up throughout the continent to ensure that those very ideals the US and their allies said they stood for, never happened and that the population remained in the pattern of working hard to buy things that they did not really need. It was depressing when to notice that for some people to be rich many others had to be poor, that all our school years had been spent programming us to serve this faceless tyrant and that this is what our futures would look like no matter what we did or tried. In our semi-innocence, we saw the vestibular as the ultimate trap set by the powerful to make us join their vampire world. As the exam approached, it was as if we were heading towards the exit door from a dream-place where, as John Lennon put it in his song “Imagine”, everyone would live for today.

However, regardless of our clarity about this warped reality, we were still privileged kids from the Zona Sul who were interested in having a good time and the year of 1980 was to be one of exacerbated contradictions. For me, the strangest of these inconsistencies was that being part of the weed/musician club into which my identity had so firmly fused, had a strangely positive effect on my studies. I had no problem sleeping, didn’t have stress-linked skin disorders and was always even-tempered. Also, with some of us playing guitar well and being more street wise than the average student, we were no longer viewed as the school’s weirdos but instead had the status of cool dudes. We had the best parties and even the most attractive girls began to notice us.

*

In the middle of our most hectic school year, a new Mecca appeared: the region of Visconde de Mauá, a collection of little country villages nestled in Serra da Mantiqueira mountain range right in between the cities Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. When I was a child, before the family set off in the Teresópolis venture, we would rent bungalows and take farm-style vacations there. Many of the Inns and indeed the farms had been set up by immigrants from the Old Continent. This and the more temperate mountain air made the place very similar to the central European countryside where Dad had grown up. He loved to go there as he could enjoy quality time with his children in much the same ways he had enjoyed his childhood. He would take Sarah and I to see cows being milked in the early hours, and delighted himself in explaining how farm life worked, telling us how chickens, pigs, turkeys, sheep and other animals were raised.

In the early 1980s, Visconde de Mauá had become a refuge for pretty-well the only authentic hippies that still existed in Brazil. With their long and unkempt hair, and their unconventional clothes covered with Indian patterns and clumsy drawings of magic mushrooms and cannabis leaves, they were the real thing, complete social dropouts, and were too wild even for us. Their huts had an atmosphere of Celtic tents, with psychedelic drawings, portraits of Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and John Lennon drawn on the walls next to hallucinogenic references and the ever-present hippy symbol. Because of the energy around them we experienced something close to the last echoes of Woodstock, after we became closer it was like smoking the roach of a joint that giants of the past had lit up.

Mauá was about four hours from Rio and on long and rainy weekends when there was no beach life, there was no doubt that this was the place to go. The mountains, the woods and the rivers made us feel close to our British rock heroes, or at least to what we saw on the cover of their albums.

On one of our escapades from the pressure of the vestibular preparations, we managed to bring some girls from school. This was a huge novelty: we barely knew how to deal with the notion of female counterparts with the same intellectual outlook as us and, what’s more, who were actually interested in us. When they went topless at a waterfall we all took their initiative maturely, managing to keep our jaws closed.

At night, we lit a fire, opened bottles of wine and passed around the canned food. After eating, we went into our tents, took the guitars out of their covers and started to jam. The atmosphere was special. The only sound around was that of our instruments resonating into the silence of the woods. For us, the chords, the riffs and the solos were a sophisticated and emotional conversation but for the girls this was in a language that they could not understand and which made them feel left out. The original idea was to impress them, but the result could not have been more different: they kept on looking at each other, wondering what we the hell was going on.

I was the kind of guy who never picked up the signs when a girl fancied him, but even I could sense that there was some sort of tension going on between Aninha and me. Although my shyness did not allow a direct approach, I had the cunning idea of placing my sleeping bag next to hers in the tent, my thought being that she would enter the tent, I would immediately follow her and one thing would lead to another. Only the first part went according to plan. Aninha went into the tent and went straight to sleep before the jam session ended. The second part never happened. When I laid down next to her, I tried to wake her up but I was too frightened of how she might react if I insisted.

After a couple of nights, the cold became unbearable. We forgot the Anglo-Saxon rocker rubbish and one of the guys went to Maromba, the nearby hippy village, to see if there was a place for us to stay, even if that meant renting something. After three or four hours, he came back with good news: he had found a room, one room, for all eight of us and everyone was happy.

My social life was contradictory if not downright schizoid. On some weekends, I tidied my hair, put on shirts with collars, shiny leather shoes, a belt and non-jeans trousers in order to go to the gafieiras, or samba clubs, looking good. These were remnants of Samba’s glory days in the thirties and in the forties and had survived in the traditional, downtown area of Rio. They were very much in fashion, though completely separate from the druggy world that was another part of my existence. Left-wingers loved the idea that they could mix with ‘the people’ on their turf. My well-behaved friends liked going to gafieiras, but whoever claimed that they went for the dancing or for the social experience was lying. The reality was that the lure of those clubs was the scores of attractive women some new to the city, and others perhaps from the ‘wrong’ side of the Tijuca forest, but interested in young men from the ‘right’ side of the urban mountain range.

It was not only the architecture that had managed to remain intact, the big bands that played there had managed too. They were authentic, with competent old school sambistas delighted to be playing for a new genration of dancers coming from the Zona Sul. After the cheek-to-cheek dancing under improvised disco lights, there were beers, kisses, exchanges of phone numbers and invitations. Coming from different worlds, anonymity protected both sides and allowed us to have quick flings without the pressure from closer social circles. From our perspective, we were doing what everyone expected Latin American machos to do. As cold as this may sound, it was this that attracted those women to us.

Despite the successes, at the end of the day my approach to the female world was confusing. Being shy with girls who interested me and bold with girls who ultimately didn’t was no path to a healthy inner life. I had romantic expectations built up by what the songs I listened to had told me, and the films that I had seen had shown me my entire life. I had made an effort in constructing a cool persona to be desirable to an equally cool girl. Perhaps because I was not sincere enough, or perhaps because I was too impatient, or too weird, the fact of the matter was that my hopes did not materialize. To make things worse, despite the anguish, there was a part of me saying that I should not worry about these bourgeois expectations; happiness in a relationship was for squares who believed in such bullshit.

On top of the inconsistencies in the romantic department, the success of my guitar playing also added to the internal confusion. The jam sessions and the acceptance at parties projected me to a more prominent status than I had ever expected. This achievement was both a blessing and a curse. Sure, the charisma felt amazing. I sublimated frustrations and passions into my act and this added credibility to what I did. In terms of feedback, music resembled sport: the recognition or rejection was immediate and undeniable, and the buzz of people’s enjoyment was addictive. The curse was that music was to become an unfulfilled promise hovering over my life and keeping me from focusing on other goals. I never managed to translate this gift into material success: the ease of getting things right and of making them sound good is given to you and the best one can do is to be thankful regardless of what one achieves.

Anyhow, as the end of the year neared, the pressure grew exponentially. In order to pass the vestibular, music and partying had to fall into the background. There was only one month left and if I didn’t get down to some hard work there would be no good college and no one would ever forgive me at home. This required a radical step so I went to Teresópolis to isolate myself and prepare for the exams.

Where Marx went right and where Marx went wrong

Whoever dares to break all the neo-liberal, and middle class taboos and ventures to read Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto will ask himself if this is not a post that some blogger wrote one month ago. He will also start to understand why for one hundred and fifty years the words on those pages have been the greatest fear of our “beloved” bankers, industry leaders and heads of state in the Western World.

The one reason for the fear over that text is that it has made perfect sense for a century and a half; Marx’s critique is precise and undeniable and reality keeps on confirming his views. Needless to say, as Christians in the Roman times, the powers of the day have thrown many people to the lions for embracing this forbidden belief.

Before we continue, in order to rebuke the usual attacks, we will have to point out that what existed in the Soviet Union and behind the “Iron Curtain” was not communism. They saw themselves as societies working towards communism; and most ended up as flawed attempts to reach a utopic state of social equality. It is also worthwhile pointing out that they were as flawed as the western attempts to create their utopia; general contentment and optimization of resources through the “invisible hand” of the Market.

Going back to our quest for where Marx went right and where Marx went wrong, we’ll start with what went right. A recent article in nowhere less than the Rolling Stone Magazine states it succinctly in five examples:

The tendency of Capitalism to create crisis: In their need to reduce costs, companies, investors etc… drive down salaries, cut down their workforce to a point where there this affects the consumer market because there is no one left to consume. Even in the best days they come up with schemes to induce more consumption such as credit, but when this money turns into debt it only worsens the crisis in the cycle.

The creation of absurd consumerist desires: to keep the machine alive capitalism induces people to consume industrialized and technological “monstrosities” with absurd values. They become carrots on sticks for the workforce to dedicate their lives to. The examples are out there in abundance; Ferrari’s, the latest iPhones, the latest kindles, overpriced coffee Houses, overpriced holiday locations, the list is long.

Globalization: Capitalism has an insatiable appetite for new markets, not only for more people to consume its products but also to supply them with cheap labour. Could this explain why the west went as far as to finance radical Islam in order to bring those markets into the world order? This may explain why there is no place in the world to escape Capitalism. Une could argue that this just shows that this is the “logic of the world”, the “reality” as it is. But then, why do we need police and armies to back things up and to repress people who go against the system? As the neo-Marxist thinker, Slavoj Zizek, states; people find it easier to imagine a planet without natural resources than to imagine the world without Capitalism,

Tendency towards Monopoly: the logic of maximizing profits and leaving the regulation of the economy to competition leads to the big sharks eating all the other fish in the pond. One doesn’t need to go far to see small stores, small software companies, small everything almost disappearing while, as the economy recovers, it is the big guys who have managed to survive and now are having greater profits than ever.

Low wages and high profits: The essence of Capitalism is to create an “army” of workers who only have their workforce to put on the table when it comes to making a living. The people who do have the means employ them try to pay as little as they can to obtain as much profit as they can. They do this not because they are evil; it is just the logic of the system, if they do not, some ruthless competitor will end up forcing them out of business.

There are many other points that the article could have added, the main one being the founding stone of Marx’s thought: placing profit as the central motor of a society will never work. Contrary to what Wall Street, the City and their lackeys say, greed is a very bad policy maker, simply because it is self-serving. One does not need to be a rocket scientist to figure out that if you allow big profit oriented conglomerates to drive politics they will act in no one else’s interest but their own. One just needs to look at the trillionaire Bank bailouts in 2008 and their current “social responsibility” to understand why.

Until now, we have only seen where Marx went right, where did he go wrong?

The problem lies in his solutions. Actually, not in his solutions but in his lack of proposals. This is where both Marxist radicals and hysterical anti-Marxists fall into a realm of mystification and lack of understanding. Throughout his work except for some rare opinions and hints, he never really stopped to write about how a communist state would be nor how humanity would ever get there.

As we all know, his opinion was that communism is an inevitable state that we will all end up in, regardless of the route we choose. For him, communism is a utopian state of affairs where the means of production will be aimed at the community (hence the name) and not at private profit. Again, we have to mention that the mainstream theories also have their own utopia where, if left to their own devices, the selfish agents of the economy will optimize the resources available to humankind and will create generalized wealth in the most optimized way possible.

Both utopias stem out of the Judeo-Christian-Muslim messianic belief that history has a goal. For both, intelligence or the God-like qualities blown by the Almighty into mud to create Adam will eventually flower into a world of mutual understanding that will be fair for all. This is a very powerful concept that has kept not only religions, but the entire political debate alive.

For Marxists, the good days will come through a revolution, for the Monetarists they will come through the general acceptance of the Market, for the Christians they will come through the universal acceptance of Christ, for the Muslims through the universal acceptance of the prophet and for the Jews through the coming of the Messiah. There are different versions and for each of these myths but they are all saying the same thing.

It is our opinion that Marxism is the latest step of the utopian tradition, it is a natural follow up to the revolutionary Christian concept of the holy Ghost: forget all dogma, forget the laws, get along with each other and create something sacred. The problem here, as with all other Messianic views is that it privileges the future rather than the present.

As a revolutionary in Tahrir square sais at the end of the fabulous documentary The Square, after seeing his struggle being kidnapped by the Egypt’s military and by the Muslim Brotherhood, “We fought for a new way for people to relate to each other, the people have taken over the streets and now we know our strength.”

Our opinion is that he nailed the issue; the key is the here and the now, not the future not the past. The possibility for change comes to us every day and in every situation and it comes from within, it lies in the way we relate to each other, it lies is in doing the right thing, it stems from the courage of standing up against what is wrong. If people see themselves personally responsible for improving the world and their lives things can change. We all know deep inside what is wrong and it is within our reach to change them. This is not about a takeover revolution with parties, armies and new leaders but about an enormous pressure on the institutions where we work, on the organizations who make products that are vital for us, on what the state gives back to us as tax payers and on the way we relate to each other. This is about ending the “us and them” stalemate, a macro revolution based on an infinitude of micro revolutions.

Lost Samba – Chapter 20 – A Brazilian in Chile

If my parents had ever found out about my adventure in the Maracanãzinho, they would have interned me in a rehab centre, or worse. In their innocence, they never saw the signs: red eyes, munchies, hours of practicing the same solo over and over again, and inexplicable mood changes. They considered all this as being just a mere teenager phase that they thought – or hoped – I would soon grow out of.

Kristof was my main partner in crime and, in their ignorance, my parents were thrilled with my friendship with the long-haired son and grandson of prominent psychoanalysts of German descent who, by a happy coincidence, were their next-door neighbours in the Teresópolis retreat. In fact, my parents were so delighted that they agreed that I could travel with him to Chile for the half-term vacation.

The length of the bus trip was crazy: seventy-two hours, the route taking us through the entire southern region of Brazil, then into Argentina and finally crossing the Andes to Chile. Nevertheless, I was excited: not only would I be visiting another country, but would also experience real snow and there was the prospect of skiing.

After a few hours in the bus, the light drizzle that had begun in São Paulo turned into a raging storm. At around nine in the evening, something fell onto the driver’s windscreen and crashed through the glass. Luckily, he was unhurt and never lost control of the bus. However, he had to continue driving for an hour in the cold rain, precariously protected from the elements by no more than passengers’ raincoats and blankets. We stopped in a small town to wait for a replacement bus and a dry driver. This seemed to take forever and, while the other passengers were caring for the cold and shocked driver, we noticed that a party was going on in a house nearby. We couldn’t resist and crashed it. When the new bus finally turned up, we were lucky that some people noticed that we were missing and managed to find us.

As dawn broke, we found the landscape now to be entirely different from what we had experienced just a few hours earlier. As we advanced south, the subtropical forests faded, and the bus continued across the vast expanses of the pampas grasslands. In that rainy, cold and miserable weather, the long, low walls to the sides of the highway, and the sparse vegetation separating the large green pastures, resembled the little I had seen of the British countryside. The population we came across in the bus stops was also different. In the late nineteenth century, after the Brazilians abolished slavery, the authorities encouraged Germans, Italians, Japanese and Poles to settle in southern Brazil, giving this part of the country something of a European look and feel. The food was more familiar and the portions were enormous.

As we sped through Argentina heading towards the Chilean border, the pampas gradually gave way to a more hilly landscape dotted with fruit farms. Brazil is so vast and diverse that it was strange to realize that we had reached another country by road. At the rest stops, they spoke Spanish, we had never seen most of the goods on the shelves and the cashiers recoiled at our requests that they accept Brazilian Cruzeiros as payment. The crops we saw from the highway were very European: peaches, grapes, cherries and other soft fruit that can only grow in temperate climates. From here, the dry Andean cordillera started to emerge on the horizon. We soon entered a desert-like region with snow-covered mountain peaks, which had amongst the lowest population densities in the world. The air was so pure that the mountains gave us the impression of being nearby hills, although we knew they were both colossal and still distant.

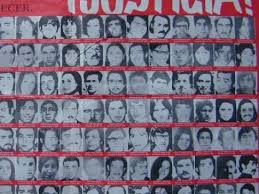

From 1973, a ruthless military dictatorship was ruling over Chile and, as we approached the border, the Brazilian passengers started voicing their opinions towards the regime. One girl, who happened to be in our year at school, took her repudiation too far: she went to the toilet and returned wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt. Madalena had the appearance of an Andean native, which, according to the Chileans on the bus, would make their military police, the carabineros, at the frontier even more furious with her statement.

She ignored our appeals for her to change her T-shirt and as we approached the isolated frontier post, we grew nervous. It was covered in snow, surrounded by tall barbed wire and kept by armed military. When the bus stopped, a heavy-set carabinero with a characteristic thick black moustache climbed on board. Expressionless, he walked up and down the aisle, and then told us all to get off. It was very cold outside and as we were going in we noticed posters with pictures of dozens of wanted “terrorists” at the entrance of the bunker-like station. Inside we were met by soldiers armed with machine guns and holding fierce-looking dogs. To everyone’s relief, minutes before leaving the bus, Madalena had the good sense of putting on a jumper and removing the T-shirt adorned with the face of the bearded revolutionary. The officers did not ask many questions but examined our travel documents carefully and we were relieved to continue on our way.

As the journey neared its end, the cordillera opened up to the narrow plains leading to the Pacific. The landscape resembled the Scottish rugged countryside: rocky, with vast fields and sparse vegetation. Kristof’s mum was waiting for us at the Santiago bus station. She was happy as we got in the car and she drove us home chatting away with her son while being polite and welcoming to me. Her comfortable house was in Las Condes, a neighbourhood that resembled an all-American middle-class suburb, with quiet streets and spacious homes bordered by well-kept gardens.

Santiago was a calm and beautiful city, set in a valley surrounded by snow-covered mountains. It was fun too as Kristof knew all the wrong people there. The first friends he introduced me to recounted their recent experiences going to an anti-dictatorship rally in the city centre. These were serious demonstrations that often descended into violent confrontations between the protesters and the military police – exactly the wrong time and place to be in a car full of illegal smoke. They had a big Cheech and Chong – a duo who did comedy films in the 1970s about smoking weed – moment while looking for a place to park, and ended up finding themselves stuck in the middle of a battle with stones and tear gas canisters flying over the roof of their car

*

The only kind of revolutionary action that still existed in Brazil was like the one I witnessed following a victory of the Brazilian team in the 1978 World Cup. Then, the police did not want celebrations near Barril 1800, a bar in Ipanema where the bohemian left congregated. Even so, we gathered in front of the bar shouting our lungs out. In the midst of the samba, we suddenly saw a wall of policemen on the other side of the street marching slowly towards us. In an instant, we went from cheering for Brazil to booing the police and chanting anti-dictatorship slogans.

In response, the police charged. We ran, but because they did not take up the pursuit, we returned and hurled stones at them. There was a lot of running back and forth, with the skirmishing carrying on until the police let their dogs loose. We ran for our asses and scattered.

In Chile, the situation far more serious. The dictatorship was at its peak and did not flinch from displaying its brutality. Chile had been a sophisticated country with high levels of education and a democratic tradition. The country’s sin had been electing a socialist government and providing asylum to leftist exiles from other South American countries. To dismantle that democracy, the USA needed a hard-right force without any scruples. This it found in the person of “Generalissimo” Augusto Pinochet.

Some of the families I met had sons, fathers, and brothers who had recently “disappeared” – seized and in all likelihood killed by the military. There was a curfew, and being out after ten at night could lead to your arrest and the risk of a beating at one of the police holding stations. Beer consumption in the streets, especially by youngsters, was a serious offense. Of course, more than once, we were in the empty streets late at night, buzzing with adrenaline and clutching beer cans. The fun was to run behind parked cars and to lie on the pavement to hide from the police patrols that passed by every twenty or so minutes.

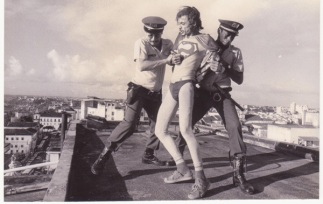

One morning, Kristof had to go to a police station to get some documents and I accompanied him. It was obvious that we were not the typical well behaved youths that the Pinochet regime expected young men to be. As soon as we entered the room we drew attention and the atmosphere became tense with menacing looks from the carabineros lined up at the door. When Kristof’s turn came, the officer took an immediate dislike to his long hair and started yelling that he had an effeminate hairstyle and that he was a pot smoking communist. That was a dangerous accusation being made by a senior Pinochet serviceman, but in the end, my Brazilian passport and Kristof’s German document did the trick of getting us out of the building intact. I will never forget another afternoon in Santiago when a man in his early thirties passed by us in a park, discretely handcuffed between two plain-clothed policemen with genuine terror in his eyes as he looked at us as if asking for help.

Because all the Latin Americans loved the Brazilians – well, with the exception of our Argentine, Paraguayan, and Bolivian neighbours – the Chileans received me well, even one of Kristof’s friends who had swastikas and other Nazi motifs covering the walls of his bedroom.

The highlight of the vacation was skiing in Farellones, one of Chile’s oldest winter-sports resorts. To get there, we took a rickety, old bus that barely managed to haul itself along the steep, winding curves of the cordillera. Although the view was magnificent, the road bordered unprotected precipices that didn’t seem to concern anyone else but me. Up at the ski slopes, I regretted only having brought knitted gloves: I kept on falling onto the powdered snow and by the end of the day, the ice that had solidified around my hands had almost frozen them. I was in pain, so while we were waiting for the bus to take us back to the warmth of Kristof’s house in Santiago, I went to a public toilet to try to bring my hands back to life with hot water. When I tried opening the door, I found that my hands had lost their grip. It must have been comical to see me trying to turn the handle in every possible way but with no success. The solution was to use the only hot liquid available: I went behind the cabin, managed to pull down my trousers and pee on my hands, hoping no one would see.

The next time we went to the slopes, I borrowed a pair of skiing gloves and from then on, the holiday was great. The weather was windless and sunny, and the slopes were empty and covered with a layer of fresh, powdery snow. The sun was so strong that we could take off our jackets and our shirts when we stopped to have lunch on the terrace of a restaurant in the middle of the slopes.

Kristof and I were enjoying ourselves so much in Farellones, that we decided to remain for a whole week. We managed to stay at a close to free student hostel. The other lodgers were a little older than us and seemed to be very reserved – indeed secretive. After they found out that we didn’t live in Chile and therefore that we were unlikely to be police spies, they opened up. In the evenings, behind the closed doors of their isolated rooms, sipping mulled wine, we had long conversations about politics and about escapes through the Andes from that very hostel. There, much more than in Brazil, leading an alternative lifestyle was a courageous statement.

*

The farewell party in Santiago was as wild as one could be under the Pinochet regime. Although it was winter, one of Kristof’s mates held it in his parents’ garden and rock and roll blasted out of the loudspeakers accompanied by a lot of booze. The only element that was missing were girls. We ended the night at the red light district of Santiago completely drunk and acting as complete idiots. However, the women were too rough for any one of us.

We awoke the following morning with bad hangovers, completely unfit to endure another seventy-two hour bus journey, this time to take us back to the prospect of the final preparations for the vestibular. However, life is full of surprises. As we made our way to our seats and stowed away our hand luggage, we noticed that the only other empty seats were the ones opposite ours. A few minutes later, as in a fantasy film, two attractive young Brazilian women entered the bus and took those free seats. As soon as we left the station, I started chatting with one of them and, soon after, Kristof swapped places with her.

An hour or so later, the bus stopped at a wine shop in the mountains. I did not have any more cash and found it strange when a fellow passenger told me to pretend I was going to buy something. Without thinking much about that odd request, I went to the cashier and asked how much the bottle in my hand was, pretending to be interested in its vintage, its provenance and tasting notes. When the bus pulled away, I found out what had been going on meanwhile: some guys were bragging that they had stolen lots of wine.

I cannot really say what I would have done had I known how they had used me. Anyhow, they had managed to lift a sizeable quantity of excellent wine – booze that we would have to drink before the following day when Brazilian customs officers would search the bus for smuggled goods. It was too late to convince almost the entire bus to return the bottles, not that such an idea had seriously crossed my mind. Instead, there was no option but to join in. Someone asked whom the guitar belonged to, and the party began.

It turned out that the guys who had “liberated” the wine were professional thieves who were going to São Paulo to steal clothes from shops and then sell them in Santiago. There was also a football player who had been away from Brazil for so long that he had forgotten how to speak Portuguese, and also some dudes from Florianópolis who had been skiing in Chile. We soon discovered that everyone in the bus had an amusing story to tell and was keen to make the most out of the three days that they were about to spend there. Together we all managed to make that bus become a big party room, or narrow corridor. The guitar playing went on through the night, with all the passengers singing and making up songs about the vehicle, the other passengers, the booze, the driver and the weed. The girl who I had started flirting with soon succumbed to my charms and we ended up having fun in the toilet at the back of the bus. This was to be my best bus journey ever.

Lost Samba – Chapter 19/02 – Problems with the police.

The interest in instrumental music became so great that promoters started to see opportunities. When the Rio Jazz Festival first started in 1978, it presented big, well-established, international names such as Joe Pass, Dizzy Gillespie and Dexter Gordon as well as most the Brazilian musicians who we were listening to. The festival’s problem was the venue: the Maracanãzinho (the Maracanã’s smaller satellite indoor stadium), the same place that had hosted the music festivals in the late sixties and the early 1970s. The Maracanãzinho’s acoustics were appalling: big rock acts, like Alice Cooper, Rick Wakeman and Genesis, had played there, but the echo had transformed their music into a painful rumble.

Regardless of the quality of the acoustics, we had to go. As the tickets were expensive, my friends and I could only afford one concert. We chose the closing one, the night featuring Jaco Pastorius’ Weather Report, followed by another star bass player, Stanley Clarke. The concert’s grand finale was to be with Jorge Ben and the bateria – or rhythm section – of the Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel samba school, the best one in Rio de Janeiro, accompanied by special guests.

The seats were divided into cheaper ones on the uncomfortable upper part where for which my friends and I had bought tickets, and the more expensive ones nearer the stage where the wealthier audience could hear the concert more clearly. Jumping down to the lower part was easy, which all my friends did. When my turn came, a policeman tapped me on the back and told me to return to my seat. Despite staying seated alone, I was holding the precious joint that we had reserved especially for the concert through our financial hardship. My friends begged me to throw it down, but as far as I was concerned, it was now mine.

There were two unwritten rules regarding spliffs at concerts. The first rule was that the lights had to have dimmed before you started burning them because, if you precipitated things, the security guards – or in the case of that concert, the policemen – would look incompetent and they’d take action against you. The second rule was that you had to be generous to strangers: this would bring good karma and would save you from watching a great concert in black and white on that day when you had none of your own.

After a long and anxious wait, a deep, formal voice broke out over the sound system to announce the bands and the event’s sponsor. After that, the stadium went dark and the whistling erupted making the place sound like a giant bat cave. A few seconds later, the stage lit up and Weather Report began playing “Birdland”, one of our favourites, with the living legend Jaco Pastorius soloing its beginning on the bass. At that point, it felt safe to light the precious. Some attractive girls sitting next to me asked for some and, of course, I did not refuse. The gig began to look promising. When the first song was halfway finished, I noticed a policeman by the entrance moving calmly over to talk to a colleague at the other entrance.

The police officer stopped in front of where I was sitting and pushed through the crowd towards me. The only thing I could do was to give the joint an awkward flick, and it split in half with a small piece falling near my foot. He picked up the evidence, handcuffed me and we paraded through the crowd, out of the arena. When leaving the concert ring, nervous, angry and stoned as I was, I heard the wrong words come out of my mouth, as if some other person was saying them: I told him that he was screwed because I had no money to give him.

Apparently ignoring my words, the officer continued to push me forward and took me down a long corridor filled with other guards until we reached a big and bright room where the military police was already holding at least another forty people. As soon as we got in, he gave me a strong punch in the stomach. This had always been my weak spot in fights, but because of the adrenaline, I felt nothing. He searched my pockets and didn’t find anything but did get hold of my ID card. After this, he handed me over to his superior, explaining to him what had happened. The captain, who was sitting behind a desk, examined my document, looked me in the eyes, then filled out a form and told me to join my new companions.

There were three categories of people in there: guys who had been caught jumping down stairs, pot smokers and two professional thieves. The latter were handcuffed and sitting on the floor next to a group of policemen who, every now and then, turned around to kick them hard with their leather boots before returning to their conversation as if nothing had happened. The rest of us pretended not to be disturbed by that violence and were busy trying to find a way out of the situation. This was a different jurisdiction from the Zona Sul and, even if I did have some cash, the cops didn’t appear to be open to bribes and it would have been a serious mistake to even suggest such a thing.

A thin Argentinian with a straggly goatee started chatting to the captain about the irrationality of keeping marijuana illegal. We were all surprised at the officer’s intelligence and civility. He accepted the arguments about the contradiction of weed being illegal while alcohol and cigarettes were as toxic – probably a lot more – but were freely available because they made millions for their manufacturers. We all joined in and he finished the conversation by telling us that, although what we were saying might well be true, the law was the law, that we knew the rules perfectly well and should abide by them.

As the drama unfolded, we could hear the mumbled sound of the concert on the other side of the wall. After a couple of hours, the cheering and the rumble ended, and the mood in the room became apprehensive. A more senior officer arrived, told the seemingly cool captain to leave and sat behind the desk without looking at us. After a few tense minutes, he turned to his assistant to say that the guys caught jumping down could go home but that the rest of us were going to spend the night in jail.

My heart missed a beat. The nightmare was becoming more and more real, and I could already see the outcome happening: the police calling my parents to release me from jail, their disappointment and the draconian measures they would take to correct my behaviour. After a long and silent half hour, the officer called his assistant to say that the maconheiros could leave. The thieves stayed on: they had a long night ahead.

When I got to the bus stop, I remembered my ID card and searched my pockets: it wasn’t there. I had left it with the police! That was too stupid to be true, but I had to walk back through the lines of hundreds of policemen, dogs, cars and vans, forced to explain to one and all my embarrassing situation until I reached the officer who had released me. He took me back to the holding room and looked inside the drawers. The document wasn’t there. He called a soldier to ask where the documents had gone and, after a while, the junior officer came back and confirmed that they had never left that room. He then asked me if I had searched my pockets correctly. I looked again and to my absolute shame, the plasticized document was deep inside my back pocket. Telling the embarrassing truth was inevitable; he looked at me, grabbed my hand to smell my fingers, muttered something unflattering and released me again.