Lost Sambista

A Brazil never seen.

Archive for the category “Book”

Photos of Rio

I have just come back from Rio de Janeiro and took these pictures. I hope you like them!

Lost Samba – Chapter 32 – Final Chapter

Some friends went camping in Lumiar, a place similar to Maua. The morning before coming back they went for a swim in the village’s dam. One of the guys saw a small whirlpool challenging him to dive in and to experience how being tossed around felt like. He under-estimated the power behind that mass of still water and was sucked into the piping and drowned.

He was 20 years old and born into a family of diplomats; an exponent of “New Brazil” seduced by a merciless whirlpool that killed him, a striking image. The invisible but immense pressure of water being held back by an artificial mechanism poetically resembled bubble of the sweet life in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro being secured by the military regime. This was like a tragic sign that the end of that era had been sealed. His body was only retrieved after his influential parents “convinced” the authorities to blast the concrete with dynamite.

As for me, one Saturday night the phone rang as I was about to leave home for a party. It was Mum calling from Teresopolis, Dad had felt ill and had been taken to hospital. The situation was serious and she needed me there, we would have to take turns sleeping with him.

When I arrived, Dad was in bed in a state of confusion; full of tubes everywhere. He seemed ashamed for being unwell and for making us get out of our way. It was mum’s turn that night and after a chat and saying good night I drove back to the house alone. I hadn’t been there for ages and returning there in such uncertain circumstances felt strange.

The next night it was my turn. His mind was starting to go and he had a delirium that he was in the boat where he had almost died of hunger and thirst all those years ago. He did not realize that I was in the room, but after some time he recovered his senses, calmed down and we said good night. At dawn I was woken up by doctors telling me to leave the room. They tried to apply CPR, but their efforts didn’t work; when they allowed me back his eyes were wide open but there was no life in them. The only reaction I could have was to go back outside, sit on the corridor’s floor and cry. It was all over without ever having started, I loved my father and had tons of respect for him, the opposite must have been true but we were never able to communicate our feelings properly to each other.

He had come from a rural Jewish village in the interior of Poland to reverse his destiny and to conquer the tropical jungle but it ended up devouring his dreams and his pain. I felt as helpless and as far away from him as he was from his own father when he was killed in Auschwitz. I was the continuity of his search for a place of sanity in an adverse world.

Lost Samba – Chapter 31/02 – Rock from Rio in the Eighties.

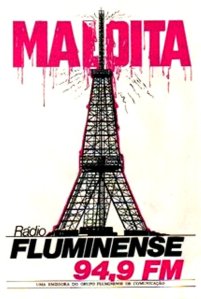

Rock and Roll took Rio over by storm. Everyone seemed to have a band, and those who did not wanted to be involved in one way or another. In the middle of this revolution, someone inherited a Radio station in Niteroi and transformed it into the first pure Rock station in town, Radio Flumnense. Now, no one needed to buy records any more to listen to Led Zeppelin, Yes, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, the Who, etc… This bonanza was short lived as they were approached by the big record companies demanding royalties. Unable to pay, they resorted to playing exclusively 80’s stuff; despite losing their pirate station aura they became avant-garde and introduced Rio’s youth to what was happening in the local and international rock scene.

Michel, a future work colleague, was an international air steward at the time; during his time off in London and in New York he would buy the latest releases of the latest bands and would deliver them freshly to the station. As these bands were from independent labels and had never been heard in Brazil, they were less of a problem to broadcast. No other station aired that kind of music and playing in their station became the passport to success for all the local bands. Arrepio included, did everything they could for them to play our songs. Radio Fluminense was to be the soundtrack of the eighties and was a phenomenon that will never be repeated.

Charles, the studio owner, started getting us gigs, and with the little money we got from them we started investing in demo tapes in order to who knows, finally get some air space in Radio Fluminense. This lead us to better recording studios where we came across impatient sound engineers despising us behind the glass windows. This new phase made us more aware of what we played and taught us a lot. But in a way the pseudo professionalism in those studios got in the way of us getting the best results. The tracks were recorded separately which made those sessions very different to what we were used to; sometimes the musician would get his part wrong or sometimes the engineer messed up and there were endless repetitions where the essence of the band dissipated into technical details.

Felipe joined the band through a Posto Nove bump in too. Although he was not attached to the Circo Voador he had become a professional actor with an important role in the play “The Twelve Works of Hercules”, that was to be the cradle of many successful careers in the Brazilian acting world. He was dying to be a lead singer in a band and therefore we had an easy job to convince him to become ours. His voice was good, his presence was superb and with him we gained a new dimension; also, his contacts could break us into circles that could make it happen.

The next step was to do his début gig. Through his connections Felipe arranged one in a bar in Ipanema. It was going to the venue’s first Rock gig after decades of quiet nights of Bossa Nova. We set up our gear in the patio with the staff regarding us as barbarians coming in from the steppes; there was no pre-amplifier or sound engineer; just our instruments, borrowed microphones and the power of Charle’s amplifiers. After we had done the sound check in the afternoon he manager came up to greet us. He was apprehensive about the volume and asked us if we could play lower but we answered that because the drums were naturally loud everyone had to be at a similar level.

At night the guests started appearing; as Felipe was doing a minor role in a soap opera at TV Globo there were one or two famous faces and many desirable future starlets appearing in the room. When the hall filled up, we started. In the middle of the second number, I heard a noise in my ear and when I looked around the manager was shouting that we were too loud. I told him again that we could not play lower because of the drums. He went down and after two numbers, he knocked on my shoulder again and told me that there was someone downstairs wanting to talk to me. I replied that I could not talk then. The next thing we saw were six police officers coming up the staircase, taking the plug out of the wall and killing the gig.

The Felipe days were short lived; he signed a contract for a big role in a TV series and gave up his musical career. I went back to the vocals but arguments started to break out, the rest of the band was more concerned about their technique than my over-confident self; Marcos and Melo were still taking private lessons, which for me was very un-rock and-rollish and they did not want to understand that I couldn’t do the same for financial reasons. On the other hand, I took the venture more seriously; I believed that if we found a sound to set us apart from the other bands we could make it big and I was prepared to invest all of my energies. Meanwhile the other guys took the band with a pinch of salt and regarded the band as a fun weekend activity.

*

The temple for goths, new romantics, quasi-punks, and other alien creatures was a night club in Copacabana, called Crepúsculo de Cubatão. The name paid homage to Cubatão, an industrial town on the coast of São Paulo state considered the most polluted place in Latin America. It was owned by Ronald Biggs, the famous British train robber, and had everything one would expect from an early eighties venue: the neo-gothic expensive futuristic look with classical overtones, girls and boys dressed up as vampires, a lot of exaggerated make up and no smell of cannabis or hint of heterosexual sex in the air. The ever-crowded door was controlled by a tiny Goth girl protected by two gigantic and un-trendy bouncers. She chose whom she would not let in by pointing at them and pronouncing the death sentence: “she/he looks like a nice guy/girl”.

Strange people started to appear in our lives talking about Post-Modernism and Nietzsche without understanding much of what they were talking about but causing a knowledgeable impression. London had become the new Jerusalem and the British magazines iD and The Face were the new Bibles; in some quarters having a sun tan was seen as a sign of belonging to the Neanderthal age. The irony about the obsession with the London standard was that coming from a semi-British background, I could have prospered big time but I stuck to my coherence and in my mind I was a defeated revolutionary who had stoically not sold out.

There was a fundamental absurdity in what was going on that I could not come to grips with: Rio de Janeiro’s natural settings did not combine with urban themes. The shallowness of the discussions about visual trends in foreign magazines and which bands and artists were free from the seventies aura had nothing to do neither with Rio’s eternal wildness nor with what I thought or intended to be. On the lighter side, it was amusing to see goths and punks walking around in black leather jackets and boots on 40 degree centigrade sunny weekends while everyone else was in their bikinis or trunks going and coming back from the beach. They looked like vampires in search of morgues to shelter in until night when they could come out and take over the city.

The Carioca middle class punks’ were another case of absurdity; the clothes they wore and the places they had to be seen were expensive and had nothing to do with Johnny Rotten screaming “no future” in London between one spit and another. The punk movement was much closer to the people crammed in buses in Sao Paulo’s outskirts and to people like me being sliced up by the economic lawnmower. We were being kicked in the face by a system that had promised a rosier world as we grew up. There was a lot of right wing talk going on about the survival of the fittest but what we saw was the survival of the ones with richer parents.

Lost Samba – Chapter 31/01 – Rock and Roll and Brazil’s silent revolution

The welcome at home was lukewarm. No one likes defeats, but still my parents were glad to have their son back and not on a risky venture that they never understood. It was also clear that Dad’s days were numbered and I wanted to try to narrow the gulf between us. Lacking better options, when the summer ended I returned to university to continue the economics course. What happened next was predictable. I didn’t belong there anymore; my contemporaries looked down on me, while my new class mates either viewed me as an incomprehensible rebel or dismissed me as an idiot who had fallen behind in his studies. My grades were bad and I hated the unforgiving truth that I’d spent an entire year out, only to return to the exact same point as where I’d left off.

However, life carried on. The healer for my pressures and disappointments was, as always, Ipanema beach and its beautiful community. One Sunday morning at Posto Nove, I bumped into Melo, an ex-class buddy from the Colégio Andrews. Melo had changed from being an introverted, skinny guy into a cool, outgoing young man with long hair. It was obvious that he had also spent plenty of time working out as his muscles were all pumped up. He was proud to tell me that he had learned how to play the guitar. Although he had never belonged to the doidão gang, we agreed to meet up for an electric session at his place after sunset. Melo asked if he could bring along his friend Leonardo, a bass player. I agreed and suggested that we also invite Marcos, a mate from university who played the drums. This was how our band was born. Initially we called ourselves “Papa Clitoris e os Oligofrenicos” (Clitoris eater and the Oligophrenics), but we soon settled on a more acceptable name, “Arrepio”, meaning “goose bumps”, a term used by surfers to describe a state of awe.

Having a band was a definite step up in the rock ‘n roll ranks, as well as being a lot of inexpensive fun and therapeutic. When the music got going, the sense of empowerment was tremendous. All life’s frustrations came storming out with crude aggressiveness from the guitar and through shouts into the microphone.

*

We began rehearsing at Melo’s place, as it was impossible to meet at mine as the neighbours had signed a petition against the noise. With Melo, however, we could be as loud as we wanted because his parents always travelled on weekends and it seemed that his neighbours weren’t troubled by the roar. We used the apartment’s study as our studio. The room overlooked the Morro do Leme favela, at the end of Copacabana. Down in the shacks, we could hear a punk band rehearsing on the same days as us. When we took a break, they would start, and vice-versa. Their lyrics were those of uneducated people, probably in the equivalent of the language used in British punk. Their anger sounded so naïve that it made us fall about with laughter. I prefer not to think what they made of us.

It didn’t take long for Melo’s neighbours to start to complain too. As in my building, they ended up circulating a petition demanding that we stop playing. This forced us to turn to a regular studio, placing us even deeper into the rock ‘n roll scene. With everyone forming bands, rock was now central for Rio’s youth and rehearsal studios became an extension of the Posto Nove scene. We bumped into the same people we saw every weekend at the beach and between sessions we got to know about the wildest parties, the best drug deals, and joined in the gossip about other bands, both well-established and up-and-coming.

After trying several studios, we ended up adopting one at the Morro de São Carlos favela. This slum was notorious for “belonging” to one of Rio’s most dangerous underworld organizations, the Terceiro Comando. The police only ventured to go up that hill in armoured vehicles and protected by helicopters. Naturally, we were apprehensive as we drove through the unpaved alleys with our expensive gear. When we finally found the studio, it was uneasy to stop the car and get out of it.

The high walls, the barbed wire and the five fierce Rottweilers that protected the sizeable studio and its grounds made it resemble the fortress of a drug lord. The owner was Marcos’ drumming teacher, Charles – pronounced Shaahrlees – a tall guy with blond curly hair extending down into a curly beard that made him resemble an ancient Greek figure. Charles had been the drummer for the legendary godfather of Brazilian funk, Tim Maia and for one of tropicália’s stars, Gal Costa. He welcomed us into the spacious studio that was still smelling of cement. We were the first to ever use the premises, but soon that space was to become one of the most popular rehearsal studios in Rio used by some of the top artists and bands in town, such as Cazuza, Hanoi Hanoi and Azul Limao. Charles never forgot us and continued offering a special price. He was also generous in allowing us to play using the gear that the big boys left behind.

Although we loved the studio and the fun of playing at full blast on professional equipment, getting to Charles’ studio never ceased to be a tense experience. Every time we drove up through the narrow streets the locals suspiciously eyed our car, unsure if we were the police, a rival gang or customers. Charles must have had agreements with both the drug lords and with the police because none of them ever touched us although sometimes he’d phone Marcos telling us not to come because something heavy was going on.

*

Parallel to the paradox of the elation of having a good band playing my creations at the same time as the situation at home was borderline desperate, Brazil was passing through an important period of its modern history.

The economic disaster and restrictive measures that the IMF imposed on the country in 1983 caused widespread discontent. But what made Brazilians especially angry was that they could not choose their president. The military’s position was that the people were not capable to make this decision and congressional representatives should be left to choose the country’s leader for them. Despite the assurances that at an unspecified point in the future they would concede presidential elections, no one bought that proposal and all democratic forces within the country united to enforce immediate change. The movement took the streets, marching under the slogan “Diretas já!” – Direct elections now!

These gigantic demonstrations took place in cities across Brazil. Following a rally in São Paulo attracting 1.7 million protesters, a rally in Rio drew more than one million people to the streets, the largest political gathering the city had ever seen. A revolution in real time was something to be part of. I squeezed my way through the crowd and climbed up a news kiosk to get a clearer view. As the first speech began, I felt some splashes on my shoulder, I looked back and there was someone peeing from the column next to me. I yelled at the idiot who excused himself and directed the flow to another angle. From then on things only got better, famous actors and artists, leading congressmen and other key political figures came on to the podium and took turns in giving memorable speeches, cheered on by the assembled masses. The rally ended with the entire crowd singing the national anthem, with barely a dry eye, forever imprinting that moment onto the Brazilian collective memory.

Brasília, the capital, was far from the main centres of population so the rulers only saw what was happening on television screens, which gave them a sense of detachment and of immunity from what was taking place on the streets. Their concession was to allow the Congress to nominate a civilian as president, Tancredo Neves, a widely respected figure who had served as a token opposition politician ever since the coup in 1964. The official candidate who they allowed to lose was the unpopular military appointed governor of São Paulo, Paulo Maluf. With Tancredo’s victory, for the first time in over 20 years Brazil was set to inaugurate a civilian as president. However, the president-elect fell seriously sick only weeks before signing in. This drama kept Brazil in suspense: no one knew how serious Tancredo’s medical condition really was, whether he could take office or if some form of conspiracy was taking place. With Tancredo hospitalised and probably in a coma, José Sarney, the vice-presidential candidate, appointed to please segments of the military, took office on 15 March 1985. A little over a month later, Tancredo died.

We were scheduled to perform our first gig on the night that Tancredo was confirmed dead. As a stunned Brazil united in mourning, we sat on the club’s doorsteps in Copacabana hoping for someone to show up. Melo anxiously paced forwards and backwards, only stopping to ask why there was no one there. We patiently explained that Brazil had just lost its rightful president, to which he replied “Really? Of what?”. He was not joking and no one could believe how anyone could be so utterly detached from reality.

Lost Samba – Chapter 30 – Running Away to São Paulo

The pressure at home had become unbearable. I decided to leave for São Paulo earlier than I’d planned with the excuse of having to prepare for the vestibular, the university entrance examination. There was no drama, probably because my parents agreed that this was a good idea. As I packed my clothes and other essentials, I felt that I was entering a new and harder phase in life, that from then on nothing would be as it was.

São Paulo was only a six-hour bus journey from Rio and there was a departure every fifteen minutes. If I travelled at night, I would arrive in the morning and would then have the whole day to find the university’s student hostel. Friends had told me that getting a place would be easy, but no one could confirm this information that as it was impossible to get through by phone.

I got to the bus terminal at about 11pm. Although it was quiet, there was still a queue at the stand for São Paulo. I stood in line and out of the blue a well-dressed guy came over to ask me if I wanted a lift to São Paulo. I said no but he insisted, explaining that he had been driving for twelve hours from up north. He was exhausted but needed to reach São Paulo the following day to work in a hospital and he was looking for company to keep him awake. To reassure me, he showed me his credentials: he was a doctor. I still wasn’t convinced but he took me to the car and opened all the doors, the boot, lifted the carpets and the benches to prove that there was nothing strange. There wasn’t, he looked like a doctor, the story was plausible and, as the ride would save me the bus fare, I said, “What the hell…OK”.

In the middle of the journey, the doctor started to say that he was tired and that he had to stop. I responded by offering to drive and showed my driver’s license. He responded by giving me a strange look, grinned and with a gentle voice he explained that he wanted to pull off the highway and spend the rest of the night with me in a hotel. “No sir!” I said firmly, “Gay action was not in the contract!”. From then we engaged in a battle of nagging versus refusal. As this went on, I started to get worried when he refused to stop to let me out of the car. When dawn broke and we had reached the outskirts of São Paulo, he realized that he wasn’t getting anywhere with me. He dropped me off at a bus stop on the edge of the highway next to a place that looked like a favela.

The next twenty minutes were to be a crash course on Brazilian urban reality. I had always known that people struggled, but it was still a shock to actually see, first-hand, what life was like.

It was still dark and it was freezing cold but there was already a crowd gathered around the unsheltered bus stop. The ramshackle canteens by here were packed with people having breakfast, the aroma of coffee being the only comforting thing around. It was obvious that most, if not all, of the people here had migrated from the Northeast in search of a better life. Their faces were similar to the ones that I had seen in my trip but their complexions were greyer, the lack of sun, the cold and the effects of life in this huge metropolis grinding them down. Although I was tired, feeling dejected, cold and a bit hungry, as I looked at the people here I couldn’t help but believe that a Higher Force wanted to show me the flipside of my adventures in the Northeast.

When my bus arrived, my fellow passengers and I crammed in like sardines. Without being able to move a finger, we passed by the massive factories of Ford, Volkswagen, Gessy Lever and other multinational companies. As the bus passed these isolated complexes in the periferia of São Paulo, some passengers got off the bus, but most were bound for the city centre. The entire journey that took at least an hour and a half. I could only begin to imagine what life was like for those souls who had to do that same journey every single working day of their lives. At night, they returned home from work in the same bus, enduring the same conditions. All this effort was to gain a miserable wage, to be treated as second-class citizens at work without any prospect of improvement.

I got off at the last stop and after getting lost several times in the city centre’s web of streets and I managed to find a bus to take me to the campus. All I wanted to arrange was a place to spend the night and get some sleep. However, when things are somehow destined to go bad, they only get worse. A strike was on and there were clashes between the students and the police over the dormitory where I was planning to spend my next few months. It had been shut down. Not knowing what to do, I went to the university’s administrative offices to explain my situation and ask for help. Despite my predicament, perhaps put off by my playboy aura and my Carioca accent, I couldn’t convince anyone that I was indeed in trouble.

Lacking any other option, I went to the student’s union. Suddenly luck smiled at me. I bumped into Carlinhos, a friend from Canoa Quebrada, the remote dream-like fishing village that I’d visited in Ceará. I explained my situation and after a few phone calls, he invited me to stay at his parents’ place, a comfortable and spacious apartment looking out across São Paulo’s skyline. His family’s hospitality was overwhelming. They treated me as if I was one of their own: They gave me a room for myself, invited me to eat and to watch television with them. In addition, there was Carlinhos’ attractive older sister, Alice, who I’d met up north. She was glad to see me again, but the last thing I needed was to mess things up by risking making a move on her.

São Paulo was much more sophisticated than Rio. Paulistas were more polite and better dressed. Everything appeared clean and well organized with elevators, buses, traffic lights, the metro system and the shops all working as they should. People were more formal than I was used to and intellectual standards seemed to higher than in Rio. I felt as if I was in a first world country. The people of my age were urban, not like the beach bums of Rio who behaved as though they were the royalty of the Zona Sul. Their trendy British-like punk-rocker styles suited them. In São Paulo, the 1980s made sense.

After a week with Carlinhos, I phoned home and explained where I was and what was going on. As expected Mum panicked and minutes later a wealthy American friend who was living in São Paulo rang up to ask why I hadn’t already looked him up. I knew Johnny from Bar Mitzvah classes and we had studied together at the Escola Americana the main reason for not having called him was that our friendship only existed because when we were kids my mum kept on pushing me as his dad was the CEO of the Brazilian branch of an important American bank.

Johnny had recently returned from Miami. Although his two older brothers had successfully established themselves there, he hadn’t liked the place and now wanted to go to college in Brazil. He was desperate for me to stay with him because in his mind I represented Rio and, believe it or not, his parents saw my presence as positive because they considered me a good student. The invitation had to be accepted because I didn’t want to risk overstaying my welcome with Carlinhos’s family. Both Johnny and I needed to prepare for the vestibular and with my parents’ help we ended up going to the same crammer, the Objetivo on Avenida Paulista, where most of the headquarters of banks and of the big corporations were located and where Johnny’s family lived in their huge apartment. My new situation was excellent. I didn’t have to lift a finger – there were two maids and a chauffeur, I had a room and free food and sometimes Johnny and I enjoyed hanging out together to chase Paulista girls impressing them with our carioca mannerisms.

In São Paulo, even the vestibular was of a higher level than that of Rio. First, there was a general multiple-choice test and a week later, there was a paper specifically focusing on the candidate’s chosen course involving writing an essay. Included on the test were subjects that weren’t in Rio’s curriculum and when I was confronted with four or five questions on Portuguese literature, which I’d never studied before, I knew that was the end of the road for me.

This was my first defeat after a long run of achieving everything that I had set out to do. I considered staying on in São Paulo for another year to try again but, amidst the height of the economic depression, even I could recognise that this was not a viable option. Also, things had taken a turn for the worse at home. Dad had suffered another heart attack and I knew that it was time to go back to Rio to be a good son for once.

Lost Sampa

Lost Samba – Chapter 29 – The Circo Voador and Parque Laje: The birth of Rio’s cool.

I arrived back in Rio absolutely exhausted. But rather than being simply pleased to be home, I now found wrong so many of the comforts – a maid to tidy up for me, a room of my own and food available whenever I was hungry – that I’d always taken for granted. I felt like a wild animal caged in a zoo, my old cosseted lifestyle now feeling too limited. My parents might have thought that I’d gone through a rough time but preferred not to try to discuss it

I felt like Icarus who had fallen from the skies because he had flown too high or like Gulliver pinned down by Liliputions for being too big. I was swimming against a current of narrow-minded conformity and fear of the new decade. I felt out of touch, like a second-class citizen who no one wanted to approach both in and out of home. It seemed as if recess time at school had ended and that everyone else had returned to class apart from me. Anyway, it was obvious that they thought that my outlook needed to change and I that had to get my act together. The atmosphere was bad. Dad’s punishment was weeks without directing a word to me, a passive-aggressive manner that I had become used to.

Going back to university was tough. We were delving into micro- and macro-economic theories, calculus and other hard-core subjects. Completely out of synch with that environment, I didn’t have the concentration and the will to carry on. The experiences of my travels, my need to make sense of what was happening, my original dreams of being a film director, the lack of people similar to me around, the lack of understanding from family and friends, the lack of a girlfriend were altogether too difficult. I asked my parents to let me spend a year working on a Kibbutz in Israel to sort my head out, but the answer was a categorical no. For them, the time for fun (as they saw my choices) was over. Now was the time to pull myself together, to work hard to build a sensible future. Certainly times were economically harsh and their argument made sense but I wasn’t strong enough and was too self-absorbed to take on board such a rational position.

To complicate things further, one day Dad felt ill at work and was rushed to hospital. Although in hindsight this was predictable given the stress he was experiencing, the news came as a shock to all of us, including me. Dad was now in his eighties and his “tropical paradise” was becoming unrecognisable. Nothing seemed to be going as planned. With a monthly inflation rate of twenty percent, the country’s economy was in a state of crisis, while Dad’s business – like so many others – was only just staying afloat. Meanwhile, Dad’s family was crumbling. As far as he was concerned, I had gone mad, and although Sarah – still his great hope – was doing well in her dental career, she had got into a bad relationship and was no longer on speaking-terms with the family. The country house in Teresópolis that was to be my parents’ retirement place had become a never ending maintenance problem, yet another millstone round Dad’s neck .

Despite all the aggravation,s Dad could not allow himself to rest. He needed to continue working to sustain the family’s lifestyle. And despite the health scare, we all took him for granted. I was too self-centred to offer any practical help and, anyway, those suggestions that I made (such as selling the business and the house so that he could enjoy retirement) were dismissed out of hand. Following the 25-years of achievement for my father in Rio, Brazil now seemed to be devouring everything it had given him. At home, there was a general sense that somehow the end was approaching, and in this our condition was not very different to that which many other families were experiencing.

Although I thought a lot about it, leaving home and telling everyone to go to hell was not an option. Back then young people in Brazil lived at home with their families until they found a proper job or got married and the concept of sharing an apartment with friends was unheard of. In anycase, there were few jobs around and the ones available paid less than my pocket money. As the tensions at home became unbearable, we somehow reached a compromise. I abandoned the economics course in Rio in order to try to get a place at a film college in Sao Paulo. I reckoned that compared to making my way into the prestigious economics course in Rio, getting accepted to study film ought to be easy. In my mind this move would put me back on track with who I was.

* * *

Beyond the realms of my family’s drama, there was the intensity of life in Rio. I was still able to appreciate some of the exciting things happening out there. The star of the moment and catching the public’s imagination was the alternative theatre group Asdrubal Trouxe o Trombone (Asdrubal Brought the Trombone). In several ways it was what my generation was waiting for: a voice of their own. By breaking away from the left-wing etiquette, this was a central player in bringing change to Rio’s – and consequently the Brazilian – cultural scene. Influenced by Monty Python, and by counter-culture in general, Asdrubal was a cultural version of the surfers and the rockers. This group of largely amateur actors and directors threw all their energy into a play called “Trate-me Leao” (Treat Me Lion). Because of their fresh approach to theatre and their humerous and easy to relate themes, the play was a tremendous success with the country’s youth and toured all over Brazil. The sketches concentrated on the everyday experiences of urban kids in search of friendship, love and adventure and who had no intention of following in Che Guevara’s steps.

All this was happening while my generation was dealing with the often painful process of reaching adulthood. A constant positive of living in Rio is that it is blessed by an array of the most beautiful beaches. No matter how stressful life might be, a calm day at the beach with friends and seeing beautiful people allows one to fleetingly forget one’s troubles. One typical glorious sunny Saturday, I was chatting with Dona Isabel in the kitchen, having my usual lunch of beef, fried onions, rice and black beans before going to the Nove. The television was on and I caught a glimpse of the Asdrubal actors announcing that they were offering acting classes. I was tempted but my beach-bum instinct won out, making me think that this was for effeminate thong-wearing fake revolutionaries of the kind that I’d do anything to avoid. This decision came to be one of my biggest ever mistakes. Many of the greatest Carioca actors and rock stars of my generation, such as the band Blitz, the singer Cazuza, comedians such as Luis Fernando Guimarães and the actress/presenter Regina Case and so many others either gave classes there or emerged from that course.

Bruno, a friend of mine, joined the classes and despite not being born to act he had a video camera and talent for filming and editing. For Asdrubal, Bruno was a heaven-sent asset and they started to ask him to film their work. As Asdrubal grew, so did Bruno. A decade later, Bruno went on to win several MTV-Brasil awards for best music video director and is he now one of Brazil’s leading video makers.

.

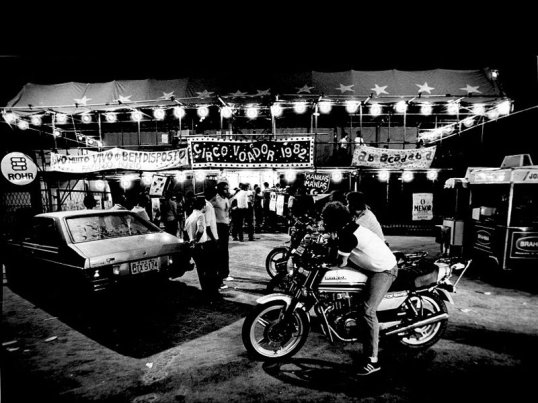

Asdrubal inherited the attention once given to the Novos Baianos, the hippy queen-bees, and to Fernando Gabeira, the revolutionary-chic former exile. Their latest initiative was a veue of their own an actual circus in Arpoador, the neighbourhood linking Copacabana with Ipanema. They named their new venue the “Circo Voador” (Flying Circus), imitating one that the Rolling Stones had used for a performance in London in the 1960s. It was here that the presentations of Asdrubal and their students took place. Jokingly the word went out that the only two musical genres that bands played under their canopy were “rock as well as roll”. They opened-up the space to local bands instead of featuring weird-looking longhaired artists from the Northeast or the soon to become outdated Brazilian music stars singing about social reform.

The musicians and lead singers were no longer the frightening, hard-core junkies of the type that led the rock scene of the 1970s. Instead, now they could easily have been (and sometimes were) fellow students, friends and neighbours merely enjoying themselves. What motivated these artists was the movement (if one could call it that) of a desire to break free from the weight of the country’s realities and to simply be part of the rock ’n roll ethos, that in their minds was a universal family. This initiative rippled throughout the country and set rock as the main 1980s cultural expression, at least for middle class youth. The Circo Voador would mark the last time that Rio would be Brazil’s musical trend setter. The centre would soon gravitate to the much larger São Paulo market, where the cultural scene was more sophisticated, in tune to innovation and more in touch with what was goung on abroad.

After going to a few Circo Voador gigs, I was convinced that I had the potential for playing to that kind of crowd. With the little money that I had left from selling Blues Boy, I bought a cheap amplifier and an electric guitar. The shift from acoustic guitar to an electric one was like changing from a bicycle to a motorbike. Now I could shake the windows of my room with just a slight pluck of a string. Because no one was happy with me at home I had to turn the volume down, but on weekends, when my parents went up to Teresópolis, my sister was at her boyfriend’s place and Dona Isable went home, I had the apartment to myself. Feeling like a insane king in a wretched castle, the beast came out and the volume got turned right up, driving our poor neighbours crazy.

I started writing songs using ideas that had come up during my travels and in jam sessions. At the same time, new ideas surfaced and I felt certain that music was my destiny. My work tried to fuse aggresive rock with Brazilian rhythms. This kind of mixture had been a controversial novelty in the days of the Tropicália and continued being used by artists from the Northeast such as the Novos Baianos and Alceu Valenca. With the 1980s rock and Brazilian music diverged, becoming more “purist”. Until then artists often combined these genres, selling their “exotic” music as developments of a more “authentic” style far removed from Rio or São Paulo. Now here was me, a guy from Ipanema with a rather odd Jewish and British background, working with traditional Brazilian music and trying to make it sound heavy with contemporary rock gear. This exoticism found no sympathy amongst the narrow-mindeded new audiences who could only appreciate either ”pure” rock or Brazilian popular music. Bands with a similar outlook to what I attempted would only establish themselves a generation later, with the likes of artists such as Chico Science and the Nação Zumbi .

* * *

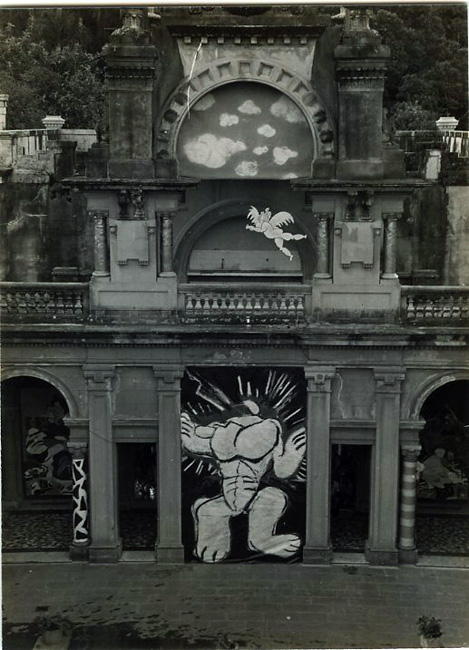

Pedro had also abandoned economics to do an art course in Rio’s Parque Lage, in an Italianate mansion set in the surreal surroundings of a tropical estate. The creation of a nineteenth century Brazilain millionaire, the grounds were so well preserved that behind the house they still had the slaves’ quarters, the senzala, a grotto with stone beds covered by limestone that gave you the creeps as one walked in.

The classes were in the mansion’s famous internal patio which had been featured in one of the most important 1960s Cinema Novo films, Glauber Rocha’s masterpiece “Terra em Transe”, and had been a busy musical venue in the 1970s where many memorable gigs took place. After a few years of silence, the beautiful location was re-opened as a concert hall and the place now competed with the Circo Voador to attract the coolest young hearts and minds in Rio.

The Parque Laje was consolidated onto Rio’s cultural map when the art course that Pedro was doing decided to get their students, along with budding artists from the Federal University’s faculty of fine arts, to paint the park’s concrete external walls. They came up with a lot of amazing and original creations and the result was going to define who was who in the “geração ‘80” (‘80s generation), the most important movement of that decade. Many of these artists went on to achieve public recognition, while other already established artists from elsewhere in the country placed themselves under their umbrella and adopted the new pop-like and youthful aesthetics, presenting themselves as the new expression of Brazilian art.

Being part of the “geração ‘80”, opened doors for Pedro, enabling him to circulate amongst the kind of “interesting people” he had always yearned to be like. Now that Pedro had been accepted, it was he who was introducing me into circles that I wanted to mingle in. In this way, I became a peripheral participant of the avant-garde of the 1980’s aesthetics that had spoiled the hippy feel of the places that had drawn me to the Northeast.