The Economist’s B.S.

The change in mood reflected from an article written two or three years ago and in the Economist’s recent cover shown above as well as in the article that follows inside is a clear portrait of this magazine’s right-wing monetarist bias, bu in this case it borders dishonesty.

The criticism is launched from a perspective that is becoming more and more obsolete and that has proven to be disastrous both in Europe and in the United States; the ne0-liberal one. The focus of the article is Brazil’s “outdated” state intervention based economy which, in the opinion of the editors, is what is scaring foreign investments away.

This is comical. For one, throughout the world banks aren’t willing to invest, not in Brazil nor anywhere else, so it is a fallacy to state that it is Brazil’s economic model that is putting investors off. The fact is that the big banks are currently sitting on their trillions, mostly obtained from the western governments salvage packages that detonated serious recessions. They are waiting for the “outside” world to be on its knees, and in this situation the money owners will be able to force the theories that the Economist represent down their populations throats.

But looking more specifically at the mood change in the Economist’s covers, the practices that they criticized in their latest publication were as true when the first picture of “promising” Brazil was issued, as they are now. So we have to ask what has changed? It surely hasn’t been the Brazilian ruling party, not has it been their economic policies. Indeed what has changed is the balance of world power where so-called peripheral countries, namely China and Russia, have been showing themselves stronger than the west in terms of economic power and in throwing their weight on geopolitical decisions, namely Iran and Syria.

It is crucial to note that these two countries have been achieving better economic results without using the recipes that the Economist suggests for Brazil. Actually it is fair to say that the Brazilian economic model is closer to the Chinese and to the Russian ones than to the western neo-liberalized ones. So why doesn’t the Economist launch a similar attack on them? It would be pathetic wouldn’t it? But yes, the Brazilian State has an enormous stake in the economy and this has been so since the 1930’s when it was put in place by Brazil’s dictator/caudillo Getulio Vargas who ruled Brazil for a great chunk of the twentieth century and who, by the way, was by no means a communist.

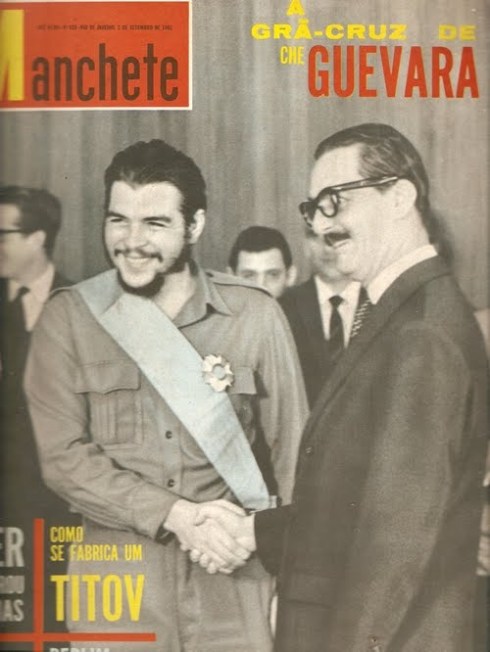

Putting things straight, the US and its European followers have consistently backed Brazil while using such an economic model as an anti-communist bastion in the “dangerous” continent of Latin America during this entire period. They strengthened Brazil when Fidel Castro became too popular, and more recently they did it again when Hugo Chavez gained too much appeal for their taste.

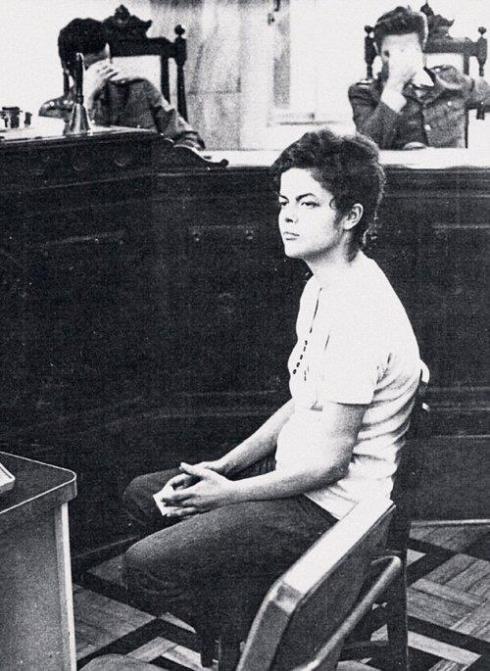

What the Economist’s sponsors would not like to see is an independent Brazil, and for that matter an independent Latin America. This may explain the phone tappings on its president and may very well also explain the “spontaneous” protests that erupted throughout the country during F.I.F.A.’s Confederations Cup with a level of organization and a spread that only professionals can achieve. It seems to us that it is no coincidence that such an article would appear right after the Brazilian government denounced the illegal actions of the American one in the United Nations, also announcing that it will be moving towards an independent route on the internet. It also seems no coincidence that this kind of bad press should appear when the ramp up for the next elections is coming up and the pro-American candidate lags in third place, far behind two left-wing candidates.

For one thing, all of this shows that Brazilians do not buy the neo-liberal vision that God has blessed America with the right answers and the moral upper hand. It also leaves the question that if the West has failed miserably in the Middle East could it be turning its eyes on Latin America?