Lost Sambista

A Brazil never seen.

Archive for the tag “Corcovado”

Lost Samba – Chapter 16/01- Jamming and Favelas in Rio de Janeiro

Back at school, my guitar-playing reputation had spread and because of this I made new friends. They were part of the group of wannabe musicians who met regularly to play together and I was thrilled when they invited me to join in. We were all curious about each other’s abilities and wanted to learn from each other. There were those who were better at solos, others who, like myself, knew more chords and were good at coming up with interesting riffs, others had drum kits, keyboards, bass guitars, and percussion instruments such as bongos, conga drums and sometimes the more typical Brazilian berimbaus and pandeiros .

The meeting point was at Fernando’s, or Fefo’s, flat on the top floor of a building in Leme with a fantastic view of Copacabana beach. For some reason he and his older brother lived alone, which made their place a free zone for our gang. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, with the excuse of studying, we sat around playing our instruments in a room that had comfortable cushions scattered around on the wood floor, a guitar amplifier, no furniture and simple art-deco style metal windows framing a view of Leme Hill. We would kickoff by playing the latest song one of us had learned and the others would gradually join in, adding more depth to the tunes. Our approach was similar to the one we took with football – this was just fun and we had no pretensions of forming a band.

On weekends, Júlio – Fefo’s older brother – and his friends joined us. They always had a lot of weed and they rolled joints so huge that we had to compact them with our fingers. After we had finished, we’d remain in a trance-like state for what seemed forever watching my friends’ puppy wagging its tail and prodding us with its paws as though to try to bring us back to life. Deploying what seemed like superhuman effort, someone would eventually manage to drag himself to the room next door where the instruments were. One or two of us would follow and start playing something, and gradually everyone else would join in. Out of this renewed energy, we arrived at a zone of inspiration out of which some really good music emerged – though the smoke had the effect that nobody would be able to remember and reproduce the ideas the following day.

Back at school, my guitar-playing reputation had spread and because of this I made new friends. They were part of the group of wannabe musicians who met regularly to play together and I was thrilled when they invited me to join in. We were all curious about each other’s abilities and wanted to learn from each other. There were those who were better at solos, others who, like myself, knew more chords and were good at coming up with interesting riffs, others had drum kits, keyboards, bass guitars, and percussion instruments such as bongos, conga drums and sometimes the more typical Brazilian berimbaus and pandeiros .

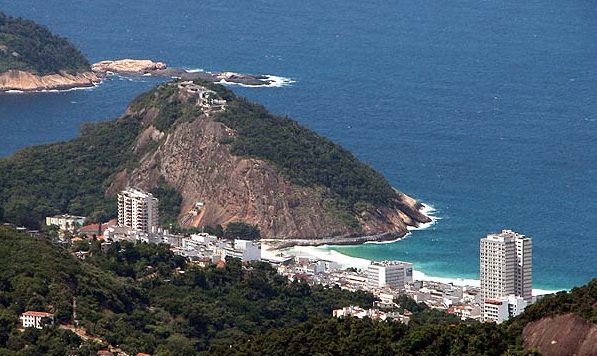

The meeting point was at Fernando’s, or Fefo’s, flat on the top floor of a building in Leme with a fantastic view of Copacabana beach. For some reason he and his older brother lived alone, which made their place a free zone for our gang. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, with the excuse of studying, we sat around playing our instruments in a room that had comfortable cushions scattered around on the wood floor, a guitar amplifier, no furniture and simple art-deco style metal windows framing a view of Leme Hill. We would kickoff by playing the latest song one of us had learned and the others would gradually join in, adding more depth to the tunes. Our approach was similar to the one we took with football – this was just fun and we had no pretensions of forming a band.

On weekends, Júlio – Fefo’s older brother – and his friends joined us. They always had a lot of weed and they rolled joints so huge that we had to compact them with our fingers. After we had finished, we’d remain in a trance-like state for what seemed forever watching my friends’ puppy wagging its tail and prodding us with its paws as though to try to bring us back to life. Deploying what seemed like superhuman effort, someone would eventually manage to drag himself to the room next door where the instruments were. One or two of us would follow and start playing something, and gradually everyone else would join in. Out of this renewed energy, we arrived at a zone of inspiration out of which some really good music emerged – though the smoke had the effect that nobody would be able to remember and reproduce the ideas the following day.

*

Almost without noticing, my friends and I had slid into the category of being the school’s doidões, the adventurous potheads. For the less sympathetic peers, we were a bunch of porra loucas, or crazy sperms, a less flattering term for people into wild things and with no sense of reality or responsibility. Although we did not see ourselves as either, we considered most of the other students to be caretas. On our side of the fence, we believed that, unlike them, we knew what life was about and how to enjoy it with no paranoias. No matter how you saw it, the divide was clear and we were not sitting on top of the fence regarding this issue.

As the gap grew bigger, we created our own subculture. The ultimate status among us became the achievement of purchasing maconha – grass – in a favela. The first boca de fumo, or drug den, I went to was in Cosme Velho, at the start of the tram line that went up to the Corcovado, Rio’s famed Christ the Redeemer statue. Everyone had contributed some cash, but only I, Juca and Haroldo, an older guy with experience in doing deals in favelas, went.

We got off the bus close to the entrance to the Rebouças Tunnel and turned into a pathway on the edge of the Tijuca forest. Haroldo told us to wait there. We were apprehensive, and after ten minutes, he returned saying that the dealer would be coming down soon and that we should have our money ready. Soon a skinny guy in Havainas and wearing no shirt arrived at the corner, looked us over and made a sign. Haroldo went to him and discretely handed over our cash. The dealer looked around to see if anyone else was watching, and in return he took five tightly packed paper sachets from under his shorts, each of which weighing around 10 grams, and handed them over. After that, Haroldo crossed the street in a hurry and we climbed on the first bus out of there feeling like commandos following a successful operation.

This risky experience gave me a proper adrenaline-rush and I often returned to make purchases. One day, the guy at our meeting point said he had no sachets on him that day but that I could get a supply if I went up into the nearby Morro dos Prazeres favela. There were two other customers in the same situation and they knew a shortcut through the forest that ended at the football field on top of the hill. We took a track that first followed alongside the heavy traffic entering the tunnel and then branched out into dense bush. At the top of the hill, we found ourselves on a football field where a group of boys were kicking a ball about. Barely acknowledging us, they knew exactly what had brought us there and continued their game.

We continued past the shacks until we got to the boca at the end of an alley. From the surrounding rooftops, boys no older than us kept watch, while a tall, scrawny mulatto with a gun stuck in the waist band of his shorts and puffing away on a huge joint approached us to demand what we wanted. Trying to hide our unease, as calmly as we could we said, “fifty grams”. He told us to wait. He soon returned, carrying a one-kilo block of marijuana – looking the size of several construction bricks – the biggest single quantity of the stuff I had ever seen.

While separating out our pieces and wrapping them in sachets, the dealer became friendlier and offered us his joint. The quality was good and the effect immediately hit us, but we were afraid of relaxing our guard. After the packets were ready, we handed over the money and an older guy came out of a nearby barraco to count it. He verified that everything was OK and went back in. After that final approval we tucked our packets in our underwear, said goobye and left. We made our way unnoticed through the muddy alleyways and past the decrepit walls of the makeshift homes. Perhaps because we were stoned, the people and the environment somehow felt familiar. Soon, I realized that we were in Santa Teresa, the neighbourhood on the edge of the Tijuca forest. From there, we hopped on a tram that was going down to the city centre. I was in a state of grace, feeling as though I was on holiday. The sun was setting and the smell of the trees wafted through the rickety, old yellow carriage as it passed by the once grand, colourfully-painted houses that characterised the neighbourhood. After the bondinho reached its final stop in town, my accomplices and I each went our separate ways through the concrete jungle of the inner city.

Incredible photo

Of all the pictures I have seen since I have started promoting Lost Samba with pictures this is by far the most fantastic.

What is it?

Well it is where the Christ stays nowadays before it was constructed. Look at the place! How did people get there? by horse? in weak cars? chariots? Can you imagine how great it must have been inside that well kept art-deco shelter with that fantastic view all around?

It doesn’t seem dilapidated at all and looks modern in a way, revealing the sophistication of Rio when it was Brazil’s affluent Capital.

How I wish I could spend an afternoon drinking beer there, or would it be tea?