Lost Samba – Chapter 26/02 – Hitchhiking into crazy times in Northeastern Brazil.

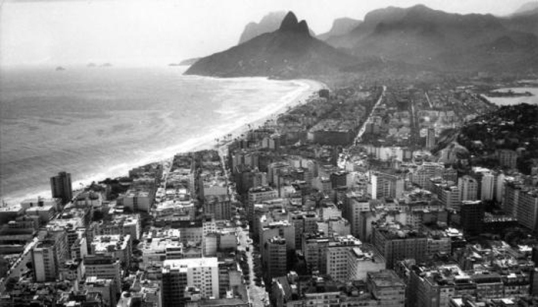

Our next stop was Aracajú, the capital of the state of Sergipe. Despite its cool-sounding name, the so-called “city” was unimaginably dull. The only good thing about that place was that we could camp on the always-empty beach in the best neighhborhood.

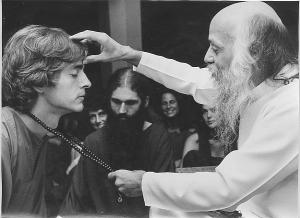

After setting up the tent, we managed to find a bar and got chatting to a pair of upper middle class women from São Paulo who belonged to Pedro’s target audience: those in their mid-thirties. One of them was into Rajneesh and had spent a lot of money on therapies to find her “inner self”. Pedro didn’t take long to show her his “avenue to truth” in our tent. By then, I had already got used to sitting back and waiting for him to score, and took my disgrace in good humor.

There wasn’t any chemistry between me and the other woman, but that didn’t prevent us from wandering down to the sea to share a joint. After an uncomfortable chat, she decided to keep her “inner self” to herself and returned to her hotel. Alone in the less than exciting Aracajú night and waiting for the tent to be free, I went back to the bar where now there had assembled a group of unattractive and drunk lesbians – surely the only openly ones anywhere in state.

Out of the blue, a dodgy looking local sat down at the table next to mine and started telling me about how high he was and that he wanted to smoke some more dope. His Mexican-style mustache, shiny shoes and tidy, tucked-in shirt gave away that we belonged to different tribes, made me not respect the unspoken law of being generous to a fellow smoker and instead I pretended not to understand. After he left, the waiter told me that he was a well-known corrupt policeman.

What felt like hours later, Pedro arrived to tell me he was going to sleep in the hotel. The next day the misery continued: the beach was awful, the people were ugly and the food was inedible. It was time to get the hell out of Aracajú.

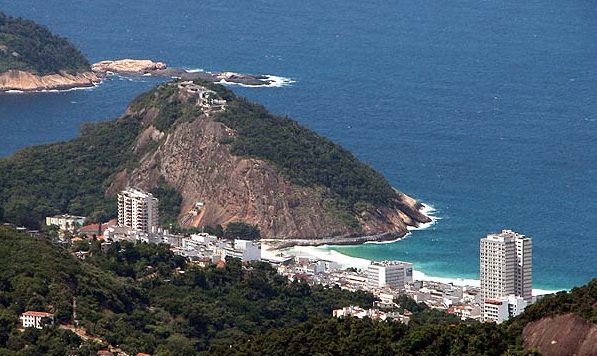

Our next destination was Maceió in Alagoas, a state best known for its picture-postcard beaches. The crystalline waters and generous vegetation with coconut trees stretching along the entire coastline were a welcome change from Aracajú’s urban tedium.

Following a recommendation that we’d received earlier in our travels, we headed to Praia do Francês (Frenchman’s Beach). To our delight, there we found suntanned girls and boys with long hair, very different from the people who dominated the scene in Arraial da Ajuda whose sense of fashion had seemed to me as being completely out of kilter with the natural style of the Northeast. Experience had taught us that the first thing to sort out was a place to stay. We asked around and someone told us about a building site with a wicker roof, the last one by the beach. When we got there, there were other guys already using the premises but this wasn’t a problem: they welcomed us and, in no time, we were accepted as part of the community.

The guys spoke highly about some very potent marijuana that a local grew and that they were about to buy. Despite facing financial wipeout, Pedro and I naturally didn’t think twice about joining the deal. Suddenly we were without any cash, but to get some more would have involved a two-hour bus ride to reach an ATM, which were still only found in large towns. Neither of us wanted to waste time to refill our pockets but at least this meant that our meagre savings would remain untouched for a bit longer.

Our salvation was the coconut plantation right just beyond our camp. We spent an entire week feeding on its produce. For breakfast and as a desert we’d eat the tender flesh of younger coconuts. Older coconuts had thicker, very nutritious meat and were our main meal, while throughout the day their water sustained us, quenching our thirst. They were hard to open and while striking them with a machete we had to be careful not to strike our fingers or hit other people. Occasionally some other campers and fishermen invited us to join in their meals to vary our diet, and we managed to survive.

Praia do Francês was great for scuba diving and I borrowed some gear and spent hours exploring the coral and sea life of the clear water. At sunset, I went for walks alongside the coconut plantation where the ocean breeze created soothing music and made the trees magically sway. Both these activities combined perfectly with the manga rosa weed that had swept away our cash.

I soon met other musicians and, at night, we became the attraction for the campers sitting around fires. However, it didn’t take long for me to begin to feel a bit uncomfortable in what had at first seemed like paradise. Praia do Francês was, in fact, a more up-market tourist destination than the south of Bahia and we, the other musicians, and our buddies from the shack were the minority, and there was a strong sense that many people looked down at us as freaks. We did not think much about it but, perhaps unconsciously, it made us decide to leave earlier than we otherwise might have.

As soon as we arrived back in Maceió, we ran straight to the city’s only cash machine, housed in a startingly futuristic-looking glass kiosk that contrasted jarringly with the surrounding colonial buildings. What a relief to indulge in a proper meal: just the typical menu of the coast – rice and beans, ground cassava, fish and an ice-cold beer to top off the meal – it wasn’t special, but it tasted heavenly after a week on an almost exclusive diet of coconut.