Translations “by the foot of the letter”

Translations “by the foot of the letter”

Amusing traslations of Brazilian coloquialisms

Translations “by the foot of the letter”

Amusing traslations of Brazilian coloquialisms

Bossa nova, guitar playing and Bahia were part of the same formative package and, as school drifted further from the radar, I discovered the Novos Baianos in IBEU’s Pandora’s Box. More than a band, they were a community of long-haired musicians from Bahia who, like the Greek poet-warriors, not only sang but also lived out the hippy dream.

Their philosophy could be synthesized in the question “Why not live this world if there is no other world?” which they asked in their good-humored samba, Besta é Tu (It’s you who’s the fool). The song reflects the eagerness of their generation to enjoy life despite what was taking place in the political arena and to distance itself from the caretas, or the squares, and their caretice. They started out as a group of artists assembled in Salvador by Tom Zé, tropicália’s musical genius. When they came down to Rio in search of opportunities, their talent and their carefree ways ended up making them the queen bees of the carioca hippies, around whom everyone and everything cool gravitated. Luck opened several doors for them: career wise, they filled in a talent vacuum left behind by most of the country’s big names, such as Chico Buarque, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso that the military had either exiled or completely censored. Music-wise, João Gilberto, the godfather of bossa nova, another bahiano, became very close to them and coached their raw talents into the highest musical standards. Meanwhile, their carioca bass player, Dadi, recruited through a newspaper advertisement, had no one less than Jorge Ben as a teacher.

In terms of their work, they did similar to what the Rolling Stones had done with the blues; they mixed rock and roll energy and authentic Brazilian themes. The result was very strong and, overall, their work reflected what all Brazilian hippies were during the military dictatorship: a force of nature. As expressing political thoughts was too dangerous, the confrontation with the system was existential, almost spiritual, therefore perhaps healthier than conventional politics as it did not involve picking up guns or resorting to violence. Instead this avenue sought resistance through being un-urban, in close contact with one’s true self, with nature, with music and with surfing in the case of Ipanema’s youth.

In fear of repression but, nevertheless, in complete disagreement with the route the country was taking, many thinking heads of that generation took shelter in a journey of self-discovery. By doing so, the Brazilian hippies dived into a strange, unique and lawless existence. Nonetheless, life went on, and around them was the intensity of Brazil; the mixture of cultures and the sensuousness of its streets still soaked in the euphoria of the 1970 World Cup triumph. Their psychedelic and counter-cultural outlook was akin to Jimi Hendrix meeting Pelé.

With so many cosmic forces behind their music, the Novos Baianos, the most visible and most colourful of the Brazilian hippies, found a record label that ended up providing them with a ranch in Jacarepaguá, in the outskirts of Rio. There they divided their time playing football, rehearsing, creating, eating vegetarian food, smoking weed and having children. The ranch would become an icon of that era.

*

If a big portion of the youth appeared to be messed up, the mainstream was even more. Under the military, Brazil had become a lost ship sailing into an economic disaster zone with a drunk and autocratic captain in command. Following a pattern that still remains around the world, while the economy was doing well, huge predatory international deals were sealed behind the scenes; Western power brokers came up with generous investments and told the military not to worry about paying back. The rampant corruption and the suppression of any form of opposition or transparency allowed a huge portion of that money to “evaporate”. However, when the banks would come back for repayment, the bill fell on the lap of people who had nothing to do with those transactions, and who had never benefited from them.

One of the main victims of this orgy of easy money was the environment. Considered as a commercial resource, thousands of forest hectares and of animal species were set to disappear in order to allow huge farms with state-of-the-art technology to appear. “Coincidentally”, most of the people who the big international banks funded to carry out these projects belonged to the backbone of the regime: the one percent of the population who owned eighty percent of the land. Brazil’s rulers needed this investment in order to silence the suggestion of appropriating unused land and handing it over to the destitute. The so called Reforma Agrária, the Agrarian Reform, still haunted the military despite their heavy hand. Long before the coup, this project had been a hot topic and blocking it had been one of the main reasons why the so-called revolution of 1964 had happened in the first place.

Regardless of this issue, most of the soil under the jungle was inappropriate for agriculture. Disregarding this simple but crucial limitation, the big farmers used the simplistic technique of burning down the woodland to clear their properties. After the flames had ceased, the earth on the new mega-farms became useless, and could only be used for pastures. This silent crime against the planet’s health continued way after the dictatorship ended and terminated a forest area larger than several European countries. This caused another problem: the forests’ eradication forced their populations into the big cities without any skills or preparation. The saddest thing was that most of these investments never brought any benefit to the economy; a lot of the burnt land had to be abandoned as, much of the time, raising cattle made no economic sense in those remote regions.

Next to such a government, the demonized, longhaired, Cannabis smoking lefties were angels. The world could only blame those young hearts for not risking their lives to fight against that machinery.

For those Brazilians afraid of what the “gringos” will say about them.

A little while ago I wrote about how we are trying to get our son to say ‘please’ when he asks for things. It seems to be more important than ever now as he often throws a tantrum at the first opportunity whenever he wants anything, but if we ask him to say please he will usually calm down.

It doesn’t mean that I am being polite when I say ‘please,’ it just means that I had it drilled into me at every opportunity when I was a child. Most Brazilians, though, don’t have this habit drilled into them and so don’t say ‘por favor’ and if they do then they are usually being very formal. So when they omit ‘please’ at the end of a request it doesn’t mean they are rude, it just means they seem rude to an English speaker.

When I wrote that post it got me…

View original post 888 more words

My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

There was no other place to go in Rio de Janeiro other than the same British School that had practically expelled me years ago. This was an expensive and risky choice as my class would be the first one in the school’s history to prepare for that exam and we would be the oldest pupils the school had ever taught. In addition, mirroring the downturn in the British economy, things had changed there; the disciplinarian headmaster had long gone and the current one, a greasy guy with thick glasses and the face of a drunk bulldog was very different. Apart from having a lot of severe nervous ticks and a posh accent that we made fun of, he did not have a clue about how to deal with pubescent teenagers.

Educationally it was a bad time to study at that school, but in terms of fun…With the exception of our Maths teacher, Mr. Bindley, a heavy ex-rugby player from Northern England, the rest of the staff was also unable to have any authority over our class. This allowed us to rule the school and to do all the wrong things available for boys between the ages of 14 and 16. We did scary stuff, like sticking our unsolicited hands into girls’ skirts, exploding the good students’ notebooks in the ventilator, flushing goldfish down the toilet and getting drunk during school hours.

Although the school taught the same curriculum as similar schools in Britain, neither I nor the American guys who I teamed up with, would ever take anything of value out of those classes. At the end of the year, I had to tell Dad he was wasting his hard-earned money. With all that craziness in the classroom, it would require a super-human effort to step above that nonsense and to succeed in an exam I was not even sure I wanted to take. The burden of that responsibility was too heavy; after all, I was only 15 and my parents had not raised me to face that kind of challenge and even if they had, changing my good life in Rio de Janeiro for one in a school in the UK that would put me “in line” was a grim prospect.

Parallel to the anguish of what to do about my education and me, Mum came up with the suggestion that I should learn the guitar. As a toddler I had been promising on the flute, and if I became good with the strings, my ability could help me open the doors of popularity. There was already an excellent hand-made guitar at home; Sarah’s Del Vecchio which she never touched. For once, motherly advice turned out to be spot on and, unable to take school seriously, popular or not, I dived deeply into the instrument and turned that carved wooden box into a lifelong friend.

The private teacher was slim and his pale greasy face was covered in pimples that blended badly with his African features. He looked and dressed like a nerd, but was impressive on the guitar. He had been a rocker, but had converted to Bossa Nova fundamentalism and this was what he taught. In the beginning, I wasn’t too happy: I wanted to play like Jimi Hendrix while he only taught me the pure João Gilberto style. His homework was painful, it took a lot of effort to get my fingers to hold down the strings in spider-like positions and do those jazz chords. It was a tough learning curve, but when fluency arrived and the left hand did its thing while the right hand tapped the samba, the sweetest music came streaming out. From that moment on, I had found not only a state of mind that brought me harmony but I also found something to love. However, as the guitar took a central role in my existence, the O-levels became ever more distant.

As we only had classical music records at home, my source to the songs and to the styles I wanted to learn was the library at IBEU (Instituto Brasil-Estados Unidos, the Brazil United States Institute), located near our former flat in Copacabana. Set up to demonstrate the US was Brazil’s friend and to ensure an American cultural presence in Rio de Janeiro, the Institute’s shelves had tons of vinyl long play records, LPs, of famous and obscure Brazilian artists whom I began to like and to learn. It also had a respectable collection of international and national rock and pop titles. As those LP’s piled onto the old record player in my room, the sudden access to such a variety of music made the world begin to seem a broader place.

The IBEU was not only about accessing new musical worlds; they also had books and, therefore, the library also helped to expand my literary horizons. I had started earlier with the entire collections of Asterix and Tintin and by now I had grown out of those and had discovered Jorge Amado. My first book was “Capitães de Areia” (“Sand Captains”) about street boys in Salvador, Bahia, which had blown me away. Its pages described the intense life and the difficulties street kids in Salvador encountered due to poverty, ignorance and racial prejudice, before “New Brazil” had stepped in.

Although the entire collection of his work was available in the shelves of the library of one of Uncle Sam’s hubs, Amado was a self-proclaimed communist as most other important intellectuals of his generation were. Similarly to the Cinema Novo’s film makers, his work showed how the so-called masses were sophisticated and had rich lives when compared to the neurotic, urban, white nouveaux riches. After that first book I went on to read all his other ones, their pages were intense and filled with Brazilian sensuality. That literature had the effect of making my attention gravitate towards what happened outside the surrealism of home, religion and of school. His writing drew my attention towards the huge celebration of life in the melting pot of races and cultures that is Brazil.

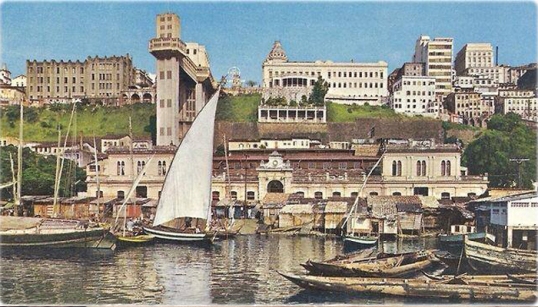

Through Jorge Amado I discovered Bahia at the heart of the fascinating country my parents had moved to. It was the Mississippi Delta of the Portuguese speaking world and, with the exception of Haiti, the most African place in the world outside the actual continent. Unlike most black people in the world, the Bahianos were proud of their origins and lived accordingly, not as a political statement, but just because this is how they had always lived. Along with its best writer, that state had provided the country with its most talented musicians: Dorival Caymmi, João Gilberto, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. The Samba was born there, as was Capoeira, the Brazilian dance-cum-martial art developed through the resistance of slaves to their destiny.

It was not only me who was fascinated with Bahia in the 1970s; the abundance of unexplored beaches and its Afro-Brazilian atmosphere transformed that part of Brazil into the ultimate destination for the nation’s hippies. There was something shining out of there that allowed people to connect with their country in a way that was more powerful and more genuine than the Californian style that the Zona Sul of Rio de Janeiro was adopting. Coincidentally, this was close to the time when the greatest Capoeira master of his days, mestre Camisa, a disciple of the great mestre Bimba, arrived from Salvador and popularized the sport in the Zona Sul. He started training a small group of capoeristas, Gato, Peixinho, Garrincha who would later become mestres themselves and who would form with him the grupo Senzala, now divided into several diferent groups, but that would come to dominate the Brazilian and the international Capoeira scene.

When boys of my generation reached puberty, after undergoing the domestic audio-visual introduction, moved on to the age-old Brazilian tradition of being initiated in sex either by a maid or by a professional. From one moment to another, it seemed that everyone except for me and my immediate circle of friends had already done it. As none of us had hot and available domésticas, the only way out were the pros. Given our budgetary limitations, all fingers pointed in the same direction: the infamous Casa Rosa, or the Pink House.

Many fathers took their sons to the important event or at least they sponsored the excursion. This was certainly not to be my case. With Dad in his mid-1970s, sex was not on the cards and it wasn’t a subject of discussion, not even in passing conversation. As far as he was concerned, licentiousness was the preserve of maids and other promiscuous favelados. I never accepted this, but I couldn’t help but inherit something of the idea that sex was intrinsically dirty and that it should be hidden away from polite society. Nevertheless, I was dying to be initiated and saved up for months, scraping together whatever I could for the big day.

Finally we thought that the day had arrived. One Saturday afternoon, my friends and I arranged to meet after lunch, but at the very last moment our trusted guide chickened out. Not only were we all pissed off, but so too was his dad. A few weeks later, we set off alone to the Casa Rosa. We did not know how to get there but when the taxi driver heard “Rua Alice”, he knew exactly the purpose of our excursion. On our way, we discussed whether we should lie and say we were seventeen instead of telling our true age: fourteen. Some of us thought this would bring more respect and would keep us from being thrown out. I was in favour of telling the truth because the lie would make us look even more retarded.

The Casa Rosa was big and seemed to have a faded grandeur. As we approached the house, we noticed a police car parked immediately outside, causing one of the guys want to give up. As we got out of the taxi and entered the building, several policemen were on their way out and greeted us with a reassuring smile. Inside, we sat around a wooden table by the improvised dance floor and waited, the silence only broken by the afternoon samba show coming out of the black and white television under the staircase. Next to the flickering set, there was a counter with two price lists: one for the drinks and another one for the “programs”.

One-by-one, the girls came down for their matinée session. They looked nowhere close to the unobtainable beauties who watered mouths on the beaches of Ipanema and Copacabana but at least they were younger and better looking than our maids. The madam pointed to us and said:

”It’s time for the children to have milk.”

They selected us, not the other way around, and took us to their rooms. When the action was about to begin, one of the guys knocked his knee against the bed, and from his reaction, we knew it had hurt: we could hear Mauricio jumping around in pain through the thin wooden walls. Meanwhile, the rest of us slipped into a silent and nervous mood without knowing what to do.

My girl was prettier, whiter, thinner and younger than the others. As she took off her clothes and lay next to me, I remembered the porn films. She talked to me and calmed me down, and I began to explore her body. Her naked flesh felt warm, tender and good. The act was as quick as it was disappointing, but I could at least count it as my initiation as a Latin Lover. I was not the first one to appear downstairs, which was a relief. After everyone had paid, we went down the hill making fun of Mauricio’s sore knee and his wounded pride.

Check out what we are about on our welcome page and visit our Facebook page and our Tumblr blog.

Avi’s dad, Daniel, was not as lucky as mine with the stock market crash. Their family had lost a lot and perhaps because of this they lived in a small, stuffy, apartment in Copacabana. Avi’s dad was in his mid-forties and behind his rather harsh-looking features, thick moustache and cold blue eyes hid a very likeable personality. Although I was as skinny as a stick insect, he considered me a healthy influence for his chubby son. Daniel thought my pastimes were the right ones, namely that I enjoyed playing football and body surfing instead of spending the day watching television and eating sweets. Therefore my friendship with Avi was supposed to be a sporty one, and on weekends, either he would come with me to the club or we would do outdoorsy activities with his dad. The choices were walks in the Tijuca forest and picnics on faraway beaches. In the afternoons, as a compensation for the exertions of earlier in the day, we would end up in one of the several funfairs that were constantly opening up or closing down all across the Zona Sul.

After we discovered skateboards, our favourite place became the Aterro do Flamengo, a park designed by Roberto Burle Marx, Brazil’s leading landscape architect. The authorities had constructed the park on land reclaimed from the sea alongside the Guanabara Bay as a gesture to compensate Rio for losing its status of national capital. However, despite the gigantic cost, what Rio ended up with was a monumentally boring place. The “attractions” included a museum of modern art that never seemed to have any significant work on display, an area to fly model airplanes, a pond for model boats, a memorial for the Brazilian servicemen killed in World War II, playgrounds for toddlers, an old airplane for people who had never been in one before and a promenade alongside the bay. Despite this, the Aterro was a good place for beginner skateboarders like ourselves: the pathways were made of smooth cement and there were several easy ramps.

Neither Avi nor I, ever came close in terms of skateboarding skills to those of the gang who hung out on my street, let alone those of the Californians who performed impressive moves in empty swimming pools and whose photos we saw in Skateboarder magazine. In fact, we sucked. Like geeks trying to look the part, both of us had the same board, the Brazilian-made Torlay, a rigid piece of wood with two very un-cool pairs of black rubber wheels stuck under it. They broke all the time and looked embarrassing next to the imported ones with colourful semi-transparent polyurethane wheels and flexible, fiberglass boards that the cool kids used.

One morning, Avi’s dad took out a Super 8 camera to film our awkward performances. I had never seen such a camera before and, noticing my curiosity, Daniel asked if I wanted to try it out. He handed over the small, futuristic, box and explained how it worked. I gave it a go and managed to capture Avi going down the slope. When I played back the footage in the visor, I had something close to a revelation. That device for capturing time, full of control buttons and with intricate futuristic leds blimping on its lens was simply too awesome for words and for weeks I could think of nothing else. For me, this was state of the art technology, almost the same as the cameras used to make 007 films, John Wayne westerns and other movies that I loved so much.

I was so mesmerized that I asked for a Super 8 camera and a projector as my Bar Mitzvah present, a heavenly wish Jewish parents simply could not refuse, as long as it was within reason. After I got the equipment, the obsession continued; I filmed just about anything on every opportunity. After getting the films developed in the shop, I rounded up my friends and family to show the results in the darkness of my room. The débuts were big occasions and before them, I carefully edited the shots with a slicer, stuck the bits together with special glue and reviewed the cuts in a precarious retro-projector. My room smelled of chemical glue and there were filmstrips hanging everywhere but, as they say in Brazil, I was as happy as a chick in a garbage can.

This interest took a new dimension during a family trip to Bariloche, a resort high in the Argentine Andes with a European atmosphere that gave Brazilian visitors – as well as Nazis in hiding – the illusion of being in the Old Continent.

One day, we went on a boat excursion to an island in the middle of the huge Nahuel Huapi Lake, a beautiful place that had inspired Walt Disney’s artists for the backgrounds in the movie “Bambi”. The journey soon became boring. Being unable to stand the forced jokes and talks about my future, I went outside to throw bread to the seagulls that raced alongside the boat. About a half an hour later, Dad came out seemingly to interrupt the fun, but instead of bothering me again, Dad told me that he wanted to introduce me to a man he had just met who happened to be a documentary director. Bill was British and was in Latin America to make a film for the BBC about an explorer who in the nineteenth century had travelled on horseback all the way from Argentina to the United States. For me, this was the coolest thing someone could ever do – travelling to shoot a film, not the horse ride – and I decided there and then this was what I wanted to do when I grew up.

Back at home, I started using my Super-8 camera to make silent movies with my friends and took a course in which I ended up directing a short film. The workshop’s organizers liked the end result and took it to several Latin American youth festivals. The film’s name was “Cheque Matte” and the script blended two stories: one of a man playing chess with someone the viewer never saw, and the other a romance of this same character with a female mannequin that he had stolen from a shop. At the end of the film, it turns out that the protagonist was playing against the plastic dummy and he throws the board into the air saying in a low melancholic voice “My life was a game of chess.” As any other trendy film director of time, I will never know the true meaning of my film. Years later, I was flattered to learn that an Ingmar Bergman film, The Seventh Seal, had a similar plot.

My teachers considered themselves as part of the Cinema Novo movement, Bossa Nova’s cinematographic – and more politicized – sibling. The people involved in it wished to move the Brazilian cinema away from the commercial studio system and discover the country from a different perspective. Following the neo-realist trends in Europe, these filmmakers focused on poor people, who until then had been portrayed in stereotypical and peripheral ways but now they were the central characters. The movement gained importance after their main exponents, Glauber Rocha and Nelson Pereira dos Santos, won international recognition at the Cannes festival in 1964.

As I entered into a more hormonal teen phase of life, my friends and I started to use the projector for a much less demanding style of film. Anyone with any knowledge of the subject will agree that the 1970s were the golden age of porn: the action was authentic and the quasi-amateur debauchery made kids like us go wild. With hundreds of clandestine Swedish Super 8 movies passing from newsstands to the back of our wardrobes, my projector became a rare and coveted piece of gear I happily traded for a few days with borrowed films. This secret activity was to be the beginning of the end of my never-fulfilled dream of becoming a film director. With no one to share my passion, the lack of any decent film courses and the absence of parental encouragement, my interest, although ever present in the back of my mind, slowly dissipated into the tropical psychosis.

We find it strange that in a time when the western economies are going down the drain, some commentators still retain their colonialist ways of thinking that they know what is best for ex-emerging countries. The fact is that while the neo-liberals are try desperately to cling on to their failed theories, China and Russia are showing themselves more powerful than the west not only in economics but also in geo-politics. Strangely enough we don’t read articles in renowned magazines telling them what to do, after all they do not follow the neo-liberal hornbook, they are not democratic and at least Russia is as or more corrupt than Brazil. We also note that the “bastions” of laissez-fair and of incorruptibility applauded their government’s when they deplete their population’s wealth to save banks involved in a sort of corruption that overshadows what happens in Brazil by miles.

Despite all the boo-ha Brazil is still growing more that the west, and if there are no missteps they will continue to keep away from the Economist’s recipes for disaster and will follow, who knows?, the Chinese example. Actually it is good to note that China has now long surpassed the US as Brazil’s main commercial partner and that, by the way, Germany, who is leading the European recovery is by no means a neo-liberal place. There the government plays a big role harmonizing its country’s issues rather than attending to the issues of companies that “cannot fail”.

Anyway bellow goes an excellent article exposing who the Economist represents, and, in our view, who is sinking the West:

http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/09/23/the-financial-core-of-the-transnational-capitalist-class/

The institutional arrangements within the money management systems of global capital relentlessly seek ways to achieve maximum return on investment, and the structural conditions for manipulations—legal or not—are always open (Libor scandal). These institutions have become “too big to fail,” their scope and interconnections pressure government regulators to shy away from criminal investigations, much less prosecutions. The result is a semi-protected class of people with increasingly vast amounts of money, seeking unlimited growth and returns, with little concern for consequences of their economic pursuits on other people, societies, cultures, and environments.

One hundred thirty-six of the 161 core members (84 percent) are male. Eighty-eight percent are whites of European descent (just nineteen are people of color). Fifty-two percent hold graduate degrees—including thirty-seven MBAs, fourteen JDs, twenty-one PhDs, and twelve MA/MS degrees. Almost all have attended private colleges, with close to half attending the same ten universities: Harvard University (25), Oxford University (11), Stanford University (8), Cambridge University (8), University of Chicago (8), University of Cologne (6), Columbia University (5), Cornell University (4), the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania (3), and University of California–Berkeley (3). Forty-nine are or were CEOs, eight are or were CFOs; six had prior experience at Morgan Stanley, six at Goldman Sachs, four at Lehman Brothers, four at Swiss Re, seven at Barclays, four at Salomon Brothers, and four at Merrill Lynch.

People from twenty-two nations make up the central financial core of the Transnational Corporate Class. Seventy-three (45 percent) are from the US; twenty-seven (16 percent) Britain; fourteen France; twelve Germany; eleven Switzerland; four Singapore; three each from Austria, Belgium, and India; two each from Australia and South Africa; and one each from Brazil, Vietnam, Hong Kong/China, Qatar, the Netherlands, Zambia, Taiwan, Kuwait, Mexico, and Colombia. They mostly live in or near a number of the world’s great cities: New York, Chicago, London, Paris, and Munich.

Members of the financial core take active parts in global policy groups and government. Five of the thirteen corporations have directors as advisors or former employees of the International Monetary Fund. Six of the thirteen firms have directors who have worked at or served as advisors to the World Bank. Five of the thirteen firms hold corporate membership in the Council on Foreign Relations in the US. Seven of the firms sent nineteen directors to attend the World Economic Forum in February 2013. Seven of the directors have served or currently serve on a Federal Reserve board, both regionally and nationally in the US. Six of the financial core serve on the Business Roundtable in the US. Several directors have had direct experience with the financial ministries of European Union countries and the G20. Almost all of the 161 individuals serve in some advisory capacity for various regulatory organizations, finance ministries, universities, and national or international policy-planning bodies.

Estimates are that the total world’s wealth is close to $200 trillion, with the US and European elites holding approximately 63 percent of that total; meanwhile, the poorest half of the global population together possesses less than 2 percent of global wealth. The World Bank reports that, 1.29 billion people were living in extreme poverty, on less than $1.25 a day, and 1.2 billion more were living on less than $2.00 a day. Thirty-five thousand people, mostly young children, die every day from malnutrition. While millions suffer, a transnational financial elite seeks returns on trillions of dollars that speculate on the rising costs of food, commodities, land, and other life sustaining items for the primary purpose of financial gain. They do this in cooperation with each other in a global system of transnational corporate power and control and as such constitute the financial core of an international corporate capitalist class.

Western governments and international policy bodies serve the interests of this financial core of the Transnational Corporate Class. Wars are initiated to protect their interests. International treaties, and policy agreements are arranged to promote their success. Power elites serve to promote the free flow of global capital for investment anywhere that returns are possible.

Identifying the people with such power and influence is an important part of democratic movements seeking to protect our commons so that all humans might share and prosper.

The full, detailed list is online and in Censored 2014 from Seven Stories Press

Peter Phillips is professor of sociology at Sonoma State University and president of Media Freedom Foundation/Project Censored.

Brady Osborne is a senior level research associate at Sonoma State University.