Lost Samba – Chapter 26/01 – Easy riding in Bahia

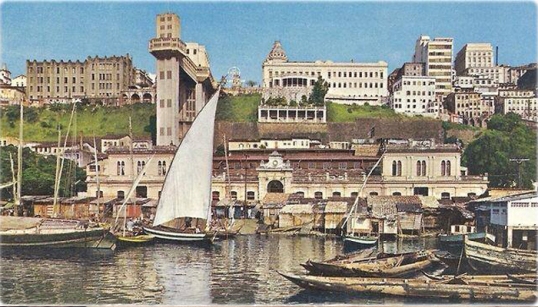

Farol da Barra. Salvador

The next stop was Salvador, where I thought we could stay with a former girlfriend who I’d met in Mauá. Michele came from Bangu, a lower-middle class neighbourhood of Rio, very different socially from my Zona Sul habitat. Michele’s mixed background gave her a complexion that could easily make her pass for Asian. She cultivated that look by wearing Indian-looking dresses and blouses and by letting her long, dark hair grow curly on the edges but straight elsewhere. She was petite and very pretty but her innocent look and her soft voice concealed a wild edge that would lead to her getting pregnant with several friends in my circle possibly being the dad.

The apartment in Salvador where Michele was staying was next to the Barra Lighthouse, one of the city’s most exclusive spots where golden middle class kids went to free carnival concerts on summer weekends. Not only were Pedro and I going to be safe from mosquitoes and have a proper bathroom, but there was a prospect for me of having some real fun at night. However, when we knocked on the door it was not Michele who opened it and we found out that the apartment belonged to her sister’s boyfriend and that there was no room for us. With the dream instantly dashed, the only way for us to hang out in that privileged spot was to sleep on the stage of the Barra Lighthouse. With summer now at its peak, there were concerts almost every night, which meant that to sleep there we would have to wait for everyone to leave. Then, at around three in the morning, we could unfold our sleeping bags on the wooden floor. To our apprehension, we found that we were not alone – there were some weird characters sleeping beneath the stage. Fortunately we never interacted, apart from early in the morning when a drunkard with a hangover emerged to do a gymnastics routine.

This sleeping arrangement ended up not being as bad as we had feared. The stage was less than a block from the apartment, and Michele’s sister managed to convince her boyfriend to allow us to keep our stuff there and to use its bathroom and kitchen. Also, for me, there was the bonus that Michele could sneak me in when the others were out to be alone together.

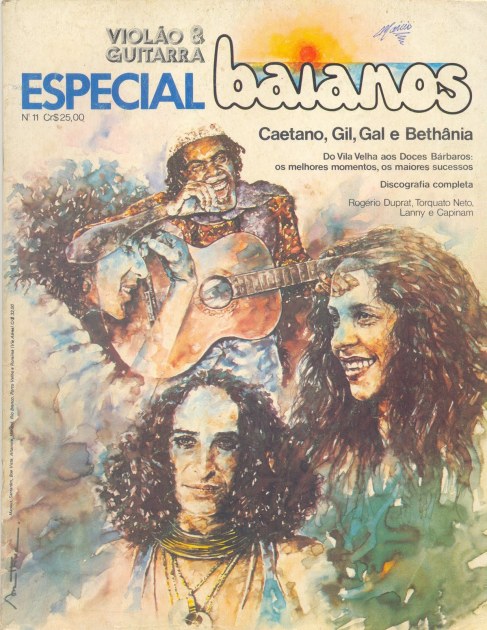

Behind the times though Salvador certainly was, the 1980s was beginning to make an impact. The age of the trio elétrico was fading, being replaced by new genres of carnival music. Reggae had touched the ears, hearts and minds of the city’s culturally dominant Afro community and a new way of playing the Jamaican rhythm emerged – a percussion-led samba-reggae fusion. The main exponent of this genre was Olodum, a band from the Pelourinho, an icon of Salvador’s African-based culture and the oldest neighbourhood in the entire country.

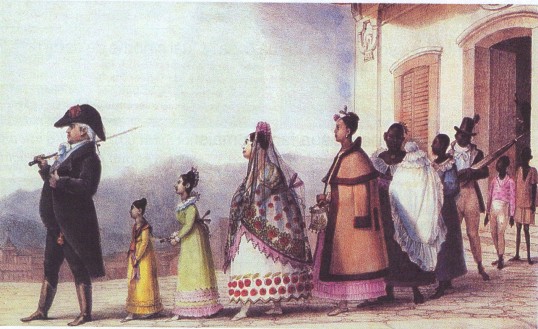

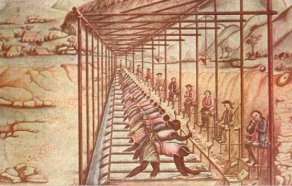

In the past the authorities used the Pelourinho’s central square as the location to punish slaves who had misbehaved, escaped or revolted. There are numerous accounts of men receiving more than a hundred lashes and then having had salt rubbed into their wounds. Now their descendants lived in the houses of their former oppressors and the area was to be listed as an UNESCO world heritage site in 1985. Olodum managed to galvanize African heritage and pride in the form of music, radiating that energy throughout Salvador. Everything that emerged in the ”Pelo” reverberated in radios and cassette players in kiosks, spreading throughout the city, blasting out samba-reggae sounds. Olodum would later make an international splash after recording alongside Paul Simon and Michael Jackson.

The other musical novelty was the more white-orientated bands with electronic keyboards and choreographed dancers on futuristic-looking vans. They were completely cheesy, playing a blend of easy to digest salsa, soca and other Caribbean styles. It was a relief that the Trio Eletrico of Dodo e Osmar – the surviving dinosaurs of Salvador’s golden carnival days – still paraded, and we had the opportunity to see them and Olodum in the pre-Carnival events.

As this was my second visit to Salvador – and now travelling as a backpacker – I felt much less of a tourist and knew what to expect. This included knowing the particularities of the various beaches, hugely important for the experience of any Brazilian coastal town. The beaches of the Northeast exuded a nostalgic aura, offering things that had long vanished in Rio. There were fishermen selling freshly-caught crabs tied to a stick, vendors of cheese that was melted on demand, stands of homemade ice cream and men walking around with sliced pineapples on tin trays. Separating the sand from the promenade were straw-roofed wooden kiosks where they served beer and exotic snacks prepared with the large range of local seafood. Fishermen with their nets and wooden boats remained from a past long before pleasure seekers ever dreamt of exposing their pale skin to the sun and, God forbid, seek a tan.

As in Rio, the beaches were the central arenas of summer. They put everyone in a state of mind that no economic crisis could intrude. The correct time to arrive was after lunch and the right time to leave was well after sunset. As the sun went down and the heat became more bearable with the beach started to attract young people seeking similar things: partying, music, interesting people and – of course – sex….perhaps even love. In a short space of time, Pedro and I soon got to know people.

Invitations to parties were frequent and always welcome. The parties, in people’s homes, were for free and entry was by invitation and hear-say. Despite the sound gear always being too weak, these parties were always great fun with joints in every room and bright people discussing political and philosophical issues. If you were not lucky to be in the bathroom having sex, the best place would be the kitchen, where guests would eat and drink. There would also always be a room where people gathered listening to a talented guitarist, and the quality of the musicians was amazing. I never understood why they never made it when so many crap rock bands in Rio and São Paulo somehow did.

Sometimes I too would play something, but I soon learned that in order to make an impression I had to stick to playing rock tunes that no one else there was comfortable to play in what was the backyard of the likes of Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and the Novos Baianos. I was no competition for the kind of stuff that they excelled at, but a Carioca who played rock was seen as something acceptable and even a welcome novelty. However, people really got excited when I played Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix tunes and sang in English, something that many of the party-goers had never before experienced.

* * *

Partying, going to the beach, meeting new people, playing guitar and trying (and sometimes succeeding) to get laid, was only part of the fun. Our means of transport – hitchhiking – was also a highlight of our travels. The routine always began the same way, by taking a bus to the first gas station on the highway. Many of the drivers told us to clear off, but some welcomed our harmless, and perhaps interesting, company.

By this time, Brazil’s railway system had all-but collapsed, and also goods were rarely transported by ship along the coast. Instead, almost all transport was by road, which was why the highways had an army of truck drivers. As any other category of workers, they were heavily exploited, sleeping very little and travelling for days on end along the country’s poorly-maintained highways, in fear of thieves and corrupt policemen. Nevertheless, they were awesome guys who had their own subculture and a great sense of camaraderie. They knew all the curves, bumps and potholes ahead, as well as the good and bad spots in terms of safety, food, fun and women. All of them had great stories and the cliché girlfriends, or even families, at every stop.

Most rides were with the driver in his cabin where they normally had a good-sized bed where we could take turns in sleeping but sometimes we were in the back, experiencing the unprotected magic of the highway. Together with the feeling of freedom that the constant wind and the open highway provided, at night there were be shooting stars above the moonlit hills, while during the day there was the strong sun bringing out the sweet smell of sugar cane from the plantations on either side of the highway.