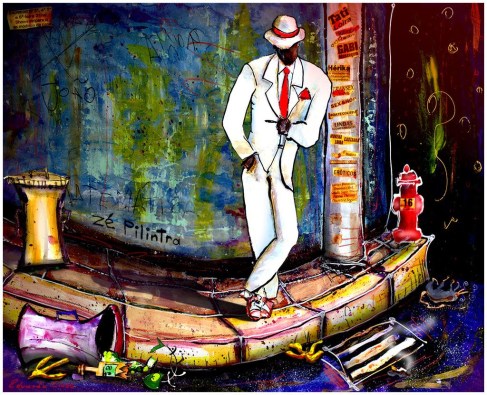

Malandros and Otarios

The painting above is of an idealized “malandro“, a popular/archetypal/folkloric figure from Rio de Janeiro that summarizes what most Cariocas try to be and how the rest of Brazil sees Cariocas. He is the wise guy from the Favela who. despite the abject poverty he was born into, by his charm and by his wits lives the great life as Chico Buarque puts it beautifully “walking on his tip toes, as treading on hearts… ”

This mythical Jack Sparrow of Rio’s streets has his opposite, the despised otario, the guy who works honestly, is dim witted, monogamous, sleeps early and is boring. From childhood every Carioca, no matter which class or color, tries to be a malandro while his parents do everything to keep him an otario.

The struggle between malandros and otarios is an old one, the otarios are the descendants of the privileged immigrants who had money to open businesses and to educate their children while the malandros are the descendants of slaves without opportunities, discriminated by the mainstream (the otarios) and who could only fight back through their malice.

This war is universal and good and evil get lost in it, both sides are right and wrong depending on the angle and the occasion. The questions that they bring up are about life itself, what is just and what is unjust? the police or the exploited? the rich or the poor? the religious or the profane? both are lovable and hateful at the same time, like all of us.

This very brief article will end with a sentence from the Brazilian tropicalist pop star Jorge Ben who presented a cure for malandragem: If the malandro knew how good it is to be honest, he would be honest just by “malandragem“. A very good, but hard, path to follow. This could be a great learning for the malandros involved in Brazilian (and world) politics since its begginings; when otarios decide to become malandros, we have a big problem…