Lost Samba – Chapter 19/02 – Problems with the police.

The interest in instrumental music became so great that promoters started to see opportunities. When the Rio Jazz Festival first started in 1978, it presented big, well-established, international names such as Joe Pass, Dizzy Gillespie and Dexter Gordon as well as most the Brazilian musicians who we were listening to. The festival’s problem was the venue: the Maracanãzinho (the Maracanã’s smaller satellite indoor stadium), the same place that had hosted the music festivals in the late sixties and the early 1970s. The Maracanãzinho’s acoustics were appalling: big rock acts, like Alice Cooper, Rick Wakeman and Genesis, had played there, but the echo had transformed their music into a painful rumble.

Regardless of the quality of the acoustics, we had to go. As the tickets were expensive, my friends and I could only afford one concert. We chose the closing one, the night featuring Jaco Pastorius’ Weather Report, followed by another star bass player, Stanley Clarke. The concert’s grand finale was to be with Jorge Ben and the bateria – or rhythm section – of the Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel samba school, the best one in Rio de Janeiro, accompanied by special guests.

The seats were divided into cheaper ones on the uncomfortable upper part where for which my friends and I had bought tickets, and the more expensive ones nearer the stage where the wealthier audience could hear the concert more clearly. Jumping down to the lower part was easy, which all my friends did. When my turn came, a policeman tapped me on the back and told me to return to my seat. Despite staying seated alone, I was holding the precious joint that we had reserved especially for the concert through our financial hardship. My friends begged me to throw it down, but as far as I was concerned, it was now mine.

There were two unwritten rules regarding spliffs at concerts. The first rule was that the lights had to have dimmed before you started burning them because, if you precipitated things, the security guards – or in the case of that concert, the policemen – would look incompetent and they’d take action against you. The second rule was that you had to be generous to strangers: this would bring good karma and would save you from watching a great concert in black and white on that day when you had none of your own.

After a long and anxious wait, a deep, formal voice broke out over the sound system to announce the bands and the event’s sponsor. After that, the stadium went dark and the whistling erupted making the place sound like a giant bat cave. A few seconds later, the stage lit up and Weather Report began playing “Birdland”, one of our favourites, with the living legend Jaco Pastorius soloing its beginning on the bass. At that point, it felt safe to light the precious. Some attractive girls sitting next to me asked for some and, of course, I did not refuse. The gig began to look promising. When the first song was halfway finished, I noticed a policeman by the entrance moving calmly over to talk to a colleague at the other entrance.

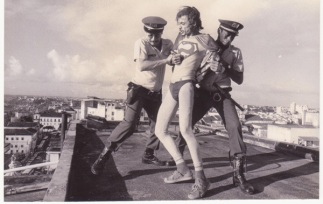

The police officer stopped in front of where I was sitting and pushed through the crowd towards me. The only thing I could do was to give the joint an awkward flick, and it split in half with a small piece falling near my foot. He picked up the evidence, handcuffed me and we paraded through the crowd, out of the arena. When leaving the concert ring, nervous, angry and stoned as I was, I heard the wrong words come out of my mouth, as if some other person was saying them: I told him that he was screwed because I had no money to give him.

Apparently ignoring my words, the officer continued to push me forward and took me down a long corridor filled with other guards until we reached a big and bright room where the military police was already holding at least another forty people. As soon as we got in, he gave me a strong punch in the stomach. This had always been my weak spot in fights, but because of the adrenaline, I felt nothing. He searched my pockets and didn’t find anything but did get hold of my ID card. After this, he handed me over to his superior, explaining to him what had happened. The captain, who was sitting behind a desk, examined my document, looked me in the eyes, then filled out a form and told me to join my new companions.

There were three categories of people in there: guys who had been caught jumping down stairs, pot smokers and two professional thieves. The latter were handcuffed and sitting on the floor next to a group of policemen who, every now and then, turned around to kick them hard with their leather boots before returning to their conversation as if nothing had happened. The rest of us pretended not to be disturbed by that violence and were busy trying to find a way out of the situation. This was a different jurisdiction from the Zona Sul and, even if I did have some cash, the cops didn’t appear to be open to bribes and it would have been a serious mistake to even suggest such a thing.

A thin Argentinian with a straggly goatee started chatting to the captain about the irrationality of keeping marijuana illegal. We were all surprised at the officer’s intelligence and civility. He accepted the arguments about the contradiction of weed being illegal while alcohol and cigarettes were as toxic – probably a lot more – but were freely available because they made millions for their manufacturers. We all joined in and he finished the conversation by telling us that, although what we were saying might well be true, the law was the law, that we knew the rules perfectly well and should abide by them.

As the drama unfolded, we could hear the mumbled sound of the concert on the other side of the wall. After a couple of hours, the cheering and the rumble ended, and the mood in the room became apprehensive. A more senior officer arrived, told the seemingly cool captain to leave and sat behind the desk without looking at us. After a few tense minutes, he turned to his assistant to say that the guys caught jumping down could go home but that the rest of us were going to spend the night in jail.

My heart missed a beat. The nightmare was becoming more and more real, and I could already see the outcome happening: the police calling my parents to release me from jail, their disappointment and the draconian measures they would take to correct my behaviour. After a long and silent half hour, the officer called his assistant to say that the maconheiros could leave. The thieves stayed on: they had a long night ahead.

When I got to the bus stop, I remembered my ID card and searched my pockets: it wasn’t there. I had left it with the police! That was too stupid to be true, but I had to walk back through the lines of hundreds of policemen, dogs, cars and vans, forced to explain to one and all my embarrassing situation until I reached the officer who had released me. He took me back to the holding room and looked inside the drawers. The document wasn’t there. He called a soldier to ask where the documents had gone and, after a while, the junior officer came back and confirmed that they had never left that room. He then asked me if I had searched my pockets correctly. I looked again and to my absolute shame, the plasticized document was deep inside my back pocket. Telling the embarrassing truth was inevitable; he looked at me, grabbed my hand to smell my fingers, muttered something unflattering and released me again.