My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

There was no other place to go in Rio de Janeiro other than the same British School that had practically expelled me years ago. This was an expensive and risky choice as my class would be the first one in the school’s history to prepare for that exam and we would be the oldest pupils the school had ever taught. In addition, mirroring the downturn in the British economy, things had changed there; the disciplinarian headmaster had long gone and the current one, a greasy guy with thick glasses and the face of a drunk bulldog was very different. Apart from having a lot of severe nervous ticks and a posh accent that we made fun of, he did not have a clue about how to deal with pubescent teenagers.

Educationally it was a bad time to study at that school, but in terms of fun…With the exception of our Maths teacher, Mr. Bindley, a heavy ex-rugby player from Northern England, the rest of the staff was also unable to have any authority over our class. This allowed us to rule the school and to do all the wrong things available for boys between the ages of 14 and 16. We did scary stuff, like sticking our unsolicited hands into girls’ skirts, exploding the good students’ notebooks in the ventilator, flushing goldfish down the toilet and getting drunk during school hours.

Although the school taught the same curriculum as similar schools in Britain, neither I nor the American guys who I teamed up with, would ever take anything of value out of those classes. At the end of the year, I had to tell Dad he was wasting his hard-earned money. With all that craziness in the classroom, it would require a super-human effort to step above that nonsense and to succeed in an exam I was not even sure I wanted to take. The burden of that responsibility was too heavy; after all, I was only 15 and my parents had not raised me to face that kind of challenge and even if they had, changing my good life in Rio de Janeiro for one in a school in the UK that would put me “in line” was a grim prospect.

Parallel to the anguish of what to do about my education and me, Mum came up with the suggestion that I should learn the guitar. As a toddler I had been promising on the flute, and if I became good with the strings, my ability could help me open the doors of popularity. There was already an excellent hand-made guitar at home; Sarah’s Del Vecchio which she never touched. For once, motherly advice turned out to be spot on and, unable to take school seriously, popular or not, I dived deeply into the instrument and turned that carved wooden box into a lifelong friend.

The private teacher was slim and his pale greasy face was covered in pimples that blended badly with his African features. He looked and dressed like a nerd, but was impressive on the guitar. He had been a rocker, but had converted to Bossa Nova fundamentalism and this was what he taught. In the beginning, I wasn’t too happy: I wanted to play like Jimi Hendrix while he only taught me the pure João Gilberto style. His homework was painful, it took a lot of effort to get my fingers to hold down the strings in spider-like positions and do those jazz chords. It was a tough learning curve, but when fluency arrived and the left hand did its thing while the right hand tapped the samba, the sweetest music came streaming out. From that moment on, I had found not only a state of mind that brought me harmony but I also found something to love. However, as the guitar took a central role in my existence, the O-levels became ever more distant.

As we only had classical music records at home, my source to the songs and to the styles I wanted to learn was the library at IBEU (Instituto Brasil-Estados Unidos, the Brazil United States Institute), located near our former flat in Copacabana. Set up to demonstrate the US was Brazil’s friend and to ensure an American cultural presence in Rio de Janeiro, the Institute’s shelves had tons of vinyl long play records, LPs, of famous and obscure Brazilian artists whom I began to like and to learn. It also had a respectable collection of international and national rock and pop titles. As those LP’s piled onto the old record player in my room, the sudden access to such a variety of music made the world begin to seem a broader place.

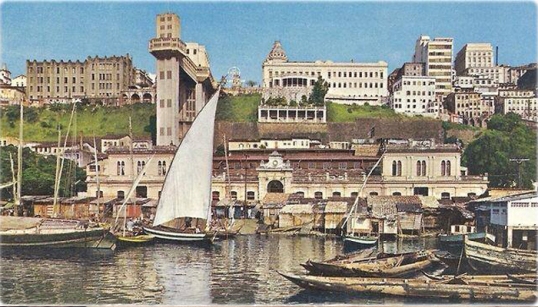

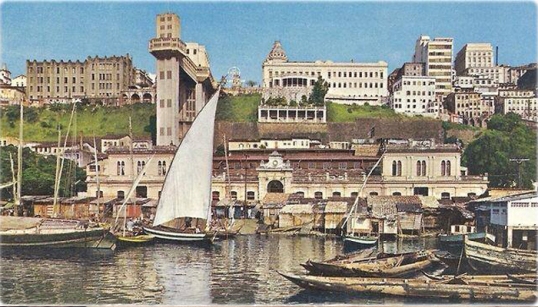

The IBEU was not only about accessing new musical worlds; they also had books and, therefore, the library also helped to expand my literary horizons. I had started earlier with the entire collections of Asterix and Tintin and by now I had grown out of those and had discovered Jorge Amado. My first book was “Capitães de Areia” (“Sand Captains”) about street boys in Salvador, Bahia, which had blown me away. Its pages described the intense life and the difficulties street kids in Salvador encountered due to poverty, ignorance and racial prejudice, before “New Brazil” had stepped in.

Jorge Amado

Although the entire collection of his work was available in the shelves of the library of one of Uncle Sam’s hubs, Amado was a self-proclaimed communist as most other important intellectuals of his generation were. Similarly to the Cinema Novo’s film makers, his work showed how the so-called masses were sophisticated and had rich lives when compared to the neurotic, urban, white nouveaux riches. After that first book I went on to read all his other ones, their pages were intense and filled with Brazilian sensuality. That literature had the effect of making my attention gravitate towards what happened outside the surrealism of home, religion and of school. His writing drew my attention towards the huge celebration of life in the melting pot of races and cultures that is Brazil.

Through Jorge Amado I discovered Bahia at the heart of the fascinating country my parents had moved to. It was the Mississippi Delta of the Portuguese speaking world and, with the exception of Haiti, the most African place in the world outside the actual continent. Unlike most black people in the world, the Bahianos were proud of their origins and lived accordingly, not as a political statement, but just because this is how they had always lived. Along with its best writer, that state had provided the country with its most talented musicians: Dorival Caymmi, João Gilberto, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. The Samba was born there, as was Capoeira, the Brazilian dance-cum-martial art developed through the resistance of slaves to their destiny.

It was not only me who was fascinated with Bahia in the 1970s; the abundance of unexplored beaches and its Afro-Brazilian atmosphere transformed that part of Brazil into the ultimate destination for the nation’s hippies. There was something shining out of there that allowed people to connect with their country in a way that was more powerful and more genuine than the Californian style that the Zona Sul of Rio de Janeiro was adopting. Coincidentally, this was close to the time when the greatest Capoeira master of his days, mestre Camisa, a disciple of the great mestre Bimba, arrived from Salvador and popularized the sport in the Zona Sul. He started training a small group of capoeristas, Gato, Peixinho, Garrincha who would later become mestres themselves and who would form with him the grupo Senzala, now divided into several diferent groups, but that would come to dominate the Brazilian and the international Capoeira scene.

Back to chapter 01 next chapter

Photo Lis Farias

Posted in

Book and tagged

Bahia,

Bossa Nova,

Bossa Nova Guitar,

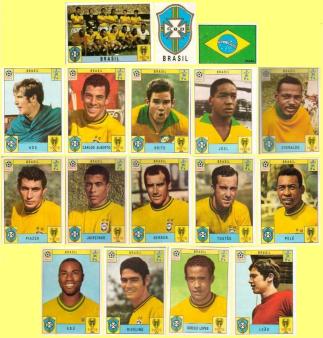

Brasil,

Brazil,

Capoeira,

Dorival Caymmi,

guitar,

Joao Gilberto,

Joao Saldanha,

Jorge Amado,

Rio de Janeiro,

Salvador