Lost Samba – Chapter 20 – A Brazilian in Chile

If my parents had ever found out about my adventure in the Maracanãzinho, they would have interned me in a rehab centre, or worse. In their innocence, they never saw the signs: red eyes, munchies, hours of practicing the same solo over and over again, and inexplicable mood changes. They considered all this as being just a mere teenager phase that they thought – or hoped – I would soon grow out of.

Kristof was my main partner in crime and, in their ignorance, my parents were thrilled with my friendship with the long-haired son and grandson of prominent psychoanalysts of German descent who, by a happy coincidence, were their next-door neighbours in the Teresópolis retreat. In fact, my parents were so delighted that they agreed that I could travel with him to Chile for the half-term vacation.

The length of the bus trip was crazy: seventy-two hours, the route taking us through the entire southern region of Brazil, then into Argentina and finally crossing the Andes to Chile. Nevertheless, I was excited: not only would I be visiting another country, but would also experience real snow and there was the prospect of skiing.

After a few hours in the bus, the light drizzle that had begun in São Paulo turned into a raging storm. At around nine in the evening, something fell onto the driver’s windscreen and crashed through the glass. Luckily, he was unhurt and never lost control of the bus. However, he had to continue driving for an hour in the cold rain, precariously protected from the elements by no more than passengers’ raincoats and blankets. We stopped in a small town to wait for a replacement bus and a dry driver. This seemed to take forever and, while the other passengers were caring for the cold and shocked driver, we noticed that a party was going on in a house nearby. We couldn’t resist and crashed it. When the new bus finally turned up, we were lucky that some people noticed that we were missing and managed to find us.

As dawn broke, we found the landscape now to be entirely different from what we had experienced just a few hours earlier. As we advanced south, the subtropical forests faded, and the bus continued across the vast expanses of the pampas grasslands. In that rainy, cold and miserable weather, the long, low walls to the sides of the highway, and the sparse vegetation separating the large green pastures, resembled the little I had seen of the British countryside. The population we came across in the bus stops was also different. In the late nineteenth century, after the Brazilians abolished slavery, the authorities encouraged Germans, Italians, Japanese and Poles to settle in southern Brazil, giving this part of the country something of a European look and feel. The food was more familiar and the portions were enormous.

As we sped through Argentina heading towards the Chilean border, the pampas gradually gave way to a more hilly landscape dotted with fruit farms. Brazil is so vast and diverse that it was strange to realize that we had reached another country by road. At the rest stops, they spoke Spanish, we had never seen most of the goods on the shelves and the cashiers recoiled at our requests that they accept Brazilian Cruzeiros as payment. The crops we saw from the highway were very European: peaches, grapes, cherries and other soft fruit that can only grow in temperate climates. From here, the dry Andean cordillera started to emerge on the horizon. We soon entered a desert-like region with snow-covered mountain peaks, which had amongst the lowest population densities in the world. The air was so pure that the mountains gave us the impression of being nearby hills, although we knew they were both colossal and still distant.

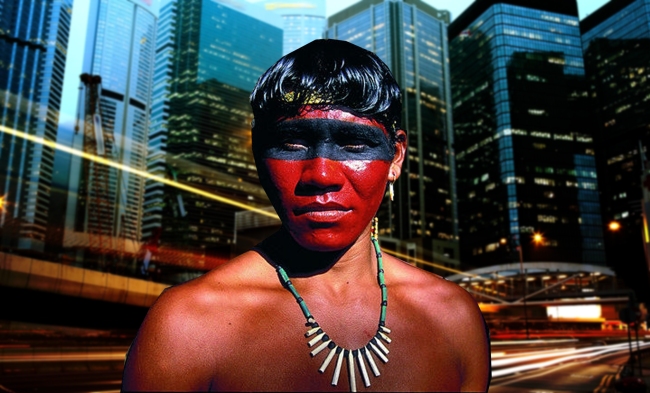

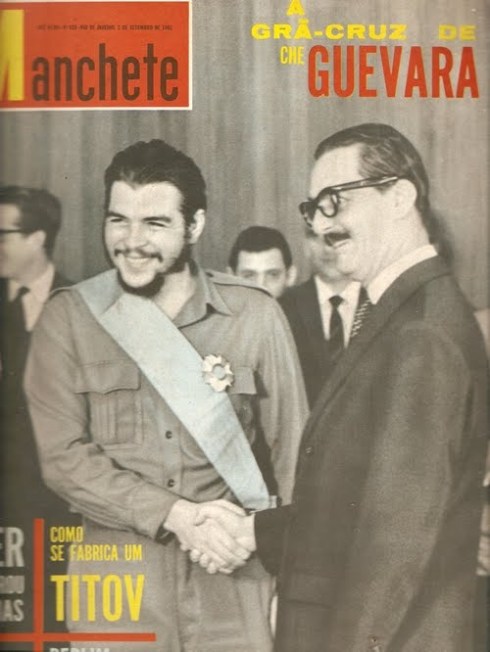

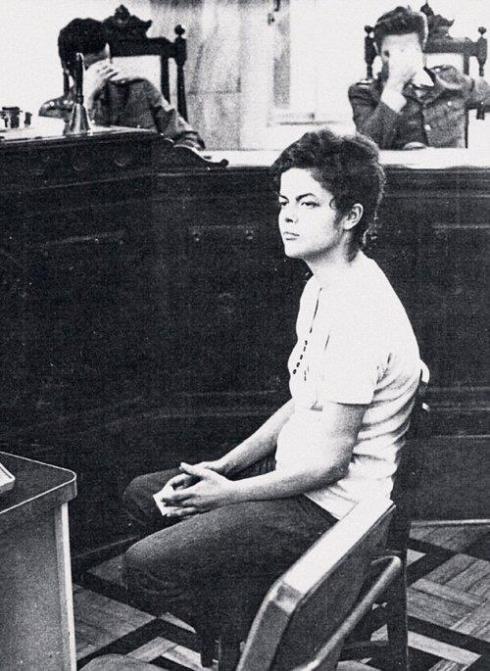

From 1973, a ruthless military dictatorship was ruling over Chile and, as we approached the border, the Brazilian passengers started voicing their opinions towards the regime. One girl, who happened to be in our year at school, took her repudiation too far: she went to the toilet and returned wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt. Madalena had the appearance of an Andean native, which, according to the Chileans on the bus, would make their military police, the carabineros, at the frontier even more furious with her statement.

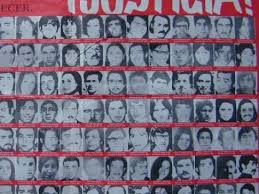

She ignored our appeals for her to change her T-shirt and as we approached the isolated frontier post, we grew nervous. It was covered in snow, surrounded by tall barbed wire and kept by armed military. When the bus stopped, a heavy-set carabinero with a characteristic thick black moustache climbed on board. Expressionless, he walked up and down the aisle, and then told us all to get off. It was very cold outside and as we were going in we noticed posters with pictures of dozens of wanted “terrorists” at the entrance of the bunker-like station. Inside we were met by soldiers armed with machine guns and holding fierce-looking dogs. To everyone’s relief, minutes before leaving the bus, Madalena had the good sense of putting on a jumper and removing the T-shirt adorned with the face of the bearded revolutionary. The officers did not ask many questions but examined our travel documents carefully and we were relieved to continue on our way.

As the journey neared its end, the cordillera opened up to the narrow plains leading to the Pacific. The landscape resembled the Scottish rugged countryside: rocky, with vast fields and sparse vegetation. Kristof’s mum was waiting for us at the Santiago bus station. She was happy as we got in the car and she drove us home chatting away with her son while being polite and welcoming to me. Her comfortable house was in Las Condes, a neighbourhood that resembled an all-American middle-class suburb, with quiet streets and spacious homes bordered by well-kept gardens.

Santiago was a calm and beautiful city, set in a valley surrounded by snow-covered mountains. It was fun too as Kristof knew all the wrong people there. The first friends he introduced me to recounted their recent experiences going to an anti-dictatorship rally in the city centre. These were serious demonstrations that often descended into violent confrontations between the protesters and the military police – exactly the wrong time and place to be in a car full of illegal smoke. They had a big Cheech and Chong – a duo who did comedy films in the 1970s about smoking weed – moment while looking for a place to park, and ended up finding themselves stuck in the middle of a battle with stones and tear gas canisters flying over the roof of their car

*

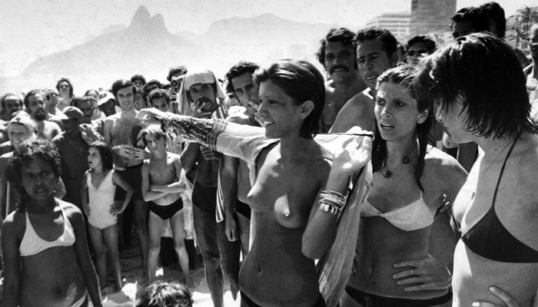

The only kind of revolutionary action that still existed in Brazil was like the one I witnessed following a victory of the Brazilian team in the 1978 World Cup. Then, the police did not want celebrations near Barril 1800, a bar in Ipanema where the bohemian left congregated. Even so, we gathered in front of the bar shouting our lungs out. In the midst of the samba, we suddenly saw a wall of policemen on the other side of the street marching slowly towards us. In an instant, we went from cheering for Brazil to booing the police and chanting anti-dictatorship slogans.

In response, the police charged. We ran, but because they did not take up the pursuit, we returned and hurled stones at them. There was a lot of running back and forth, with the skirmishing carrying on until the police let their dogs loose. We ran for our asses and scattered.

In Chile, the situation far more serious. The dictatorship was at its peak and did not flinch from displaying its brutality. Chile had been a sophisticated country with high levels of education and a democratic tradition. The country’s sin had been electing a socialist government and providing asylum to leftist exiles from other South American countries. To dismantle that democracy, the USA needed a hard-right force without any scruples. This it found in the person of “Generalissimo” Augusto Pinochet.

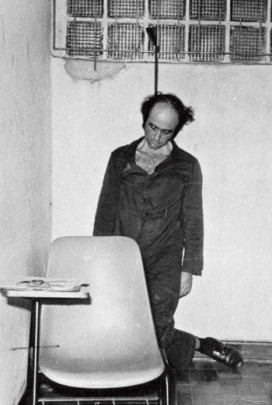

Some of the families I met had sons, fathers, and brothers who had recently “disappeared” – seized and in all likelihood killed by the military. There was a curfew, and being out after ten at night could lead to your arrest and the risk of a beating at one of the police holding stations. Beer consumption in the streets, especially by youngsters, was a serious offense. Of course, more than once, we were in the empty streets late at night, buzzing with adrenaline and clutching beer cans. The fun was to run behind parked cars and to lie on the pavement to hide from the police patrols that passed by every twenty or so minutes.

One morning, Kristof had to go to a police station to get some documents and I accompanied him. It was obvious that we were not the typical well behaved youths that the Pinochet regime expected young men to be. As soon as we entered the room we drew attention and the atmosphere became tense with menacing looks from the carabineros lined up at the door. When Kristof’s turn came, the officer took an immediate dislike to his long hair and started yelling that he had an effeminate hairstyle and that he was a pot smoking communist. That was a dangerous accusation being made by a senior Pinochet serviceman, but in the end, my Brazilian passport and Kristof’s German document did the trick of getting us out of the building intact. I will never forget another afternoon in Santiago when a man in his early thirties passed by us in a park, discretely handcuffed between two plain-clothed policemen with genuine terror in his eyes as he looked at us as if asking for help.

Because all the Latin Americans loved the Brazilians – well, with the exception of our Argentine, Paraguayan, and Bolivian neighbours – the Chileans received me well, even one of Kristof’s friends who had swastikas and other Nazi motifs covering the walls of his bedroom.

The highlight of the vacation was skiing in Farellones, one of Chile’s oldest winter-sports resorts. To get there, we took a rickety, old bus that barely managed to haul itself along the steep, winding curves of the cordillera. Although the view was magnificent, the road bordered unprotected precipices that didn’t seem to concern anyone else but me. Up at the ski slopes, I regretted only having brought knitted gloves: I kept on falling onto the powdered snow and by the end of the day, the ice that had solidified around my hands had almost frozen them. I was in pain, so while we were waiting for the bus to take us back to the warmth of Kristof’s house in Santiago, I went to a public toilet to try to bring my hands back to life with hot water. When I tried opening the door, I found that my hands had lost their grip. It must have been comical to see me trying to turn the handle in every possible way but with no success. The solution was to use the only hot liquid available: I went behind the cabin, managed to pull down my trousers and pee on my hands, hoping no one would see.

The next time we went to the slopes, I borrowed a pair of skiing gloves and from then on, the holiday was great. The weather was windless and sunny, and the slopes were empty and covered with a layer of fresh, powdery snow. The sun was so strong that we could take off our jackets and our shirts when we stopped to have lunch on the terrace of a restaurant in the middle of the slopes.

Kristof and I were enjoying ourselves so much in Farellones, that we decided to remain for a whole week. We managed to stay at a close to free student hostel. The other lodgers were a little older than us and seemed to be very reserved – indeed secretive. After they found out that we didn’t live in Chile and therefore that we were unlikely to be police spies, they opened up. In the evenings, behind the closed doors of their isolated rooms, sipping mulled wine, we had long conversations about politics and about escapes through the Andes from that very hostel. There, much more than in Brazil, leading an alternative lifestyle was a courageous statement.

*

The farewell party in Santiago was as wild as one could be under the Pinochet regime. Although it was winter, one of Kristof’s mates held it in his parents’ garden and rock and roll blasted out of the loudspeakers accompanied by a lot of booze. The only element that was missing were girls. We ended the night at the red light district of Santiago completely drunk and acting as complete idiots. However, the women were too rough for any one of us.

We awoke the following morning with bad hangovers, completely unfit to endure another seventy-two hour bus journey, this time to take us back to the prospect of the final preparations for the vestibular. However, life is full of surprises. As we made our way to our seats and stowed away our hand luggage, we noticed that the only other empty seats were the ones opposite ours. A few minutes later, as in a fantasy film, two attractive young Brazilian women entered the bus and took those free seats. As soon as we left the station, I started chatting with one of them and, soon after, Kristof swapped places with her.

An hour or so later, the bus stopped at a wine shop in the mountains. I did not have any more cash and found it strange when a fellow passenger told me to pretend I was going to buy something. Without thinking much about that odd request, I went to the cashier and asked how much the bottle in my hand was, pretending to be interested in its vintage, its provenance and tasting notes. When the bus pulled away, I found out what had been going on meanwhile: some guys were bragging that they had stolen lots of wine.

I cannot really say what I would have done had I known how they had used me. Anyhow, they had managed to lift a sizeable quantity of excellent wine – booze that we would have to drink before the following day when Brazilian customs officers would search the bus for smuggled goods. It was too late to convince almost the entire bus to return the bottles, not that such an idea had seriously crossed my mind. Instead, there was no option but to join in. Someone asked whom the guitar belonged to, and the party began.

It turned out that the guys who had “liberated” the wine were professional thieves who were going to São Paulo to steal clothes from shops and then sell them in Santiago. There was also a football player who had been away from Brazil for so long that he had forgotten how to speak Portuguese, and also some dudes from Florianópolis who had been skiing in Chile. We soon discovered that everyone in the bus had an amusing story to tell and was keen to make the most out of the three days that they were about to spend there. Together we all managed to make that bus become a big party room, or narrow corridor. The guitar playing went on through the night, with all the passengers singing and making up songs about the vehicle, the other passengers, the booze, the driver and the weed. The girl who I had started flirting with soon succumbed to my charms and we ended up having fun in the toilet at the back of the bus. This was to be my best bus journey ever.