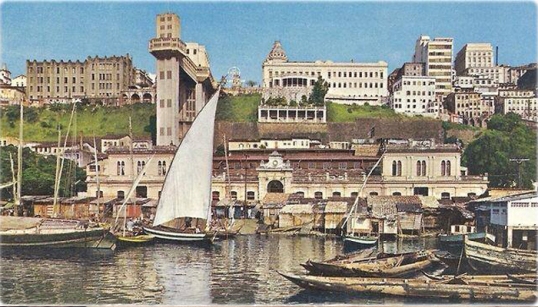

Photos of Rio

I have just come back from Rio de Janeiro and took these pictures. I hope you like them!

I have just come back from Rio de Janeiro and took these pictures. I hope you like them!

For those Brazilians afraid of what the “gringos” will say about them.

A little while ago I wrote about how we are trying to get our son to say ‘please’ when he asks for things. It seems to be more important than ever now as he often throws a tantrum at the first opportunity whenever he wants anything, but if we ask him to say please he will usually calm down.

It doesn’t mean that I am being polite when I say ‘please,’ it just means that I had it drilled into me at every opportunity when I was a child. Most Brazilians, though, don’t have this habit drilled into them and so don’t say ‘por favor’ and if they do then they are usually being very formal. So when they omit ‘please’ at the end of a request it doesn’t mean they are rude, it just means they seem rude to an English speaker.

When I wrote that post it got me…

View original post 888 more words

My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

My precocious and unusual career choice stirred things at home and, without any knowledge of the film business nor how to react to the unexpected decision, my parents did their best to respond. The wisest option would be to study cinema abroad, more specifically in the UK, but for that to happen, I would have to take the O-Levels. This was a difficult exam one took when one was around 16 in order to proceed to the next stage of the British educational system: the even harder A-Levels, the entrance exam for British universities.

There was no other place to go in Rio de Janeiro other than the same British School that had practically expelled me years ago. This was an expensive and risky choice as my class would be the first one in the school’s history to prepare for that exam and we would be the oldest pupils the school had ever taught. In addition, mirroring the downturn in the British economy, things had changed there; the disciplinarian headmaster had long gone and the current one, a greasy guy with thick glasses and the face of a drunk bulldog was very different. Apart from having a lot of severe nervous ticks and a posh accent that we made fun of, he did not have a clue about how to deal with pubescent teenagers.

Educationally it was a bad time to study at that school, but in terms of fun…With the exception of our Maths teacher, Mr. Bindley, a heavy ex-rugby player from Northern England, the rest of the staff was also unable to have any authority over our class. This allowed us to rule the school and to do all the wrong things available for boys between the ages of 14 and 16. We did scary stuff, like sticking our unsolicited hands into girls’ skirts, exploding the good students’ notebooks in the ventilator, flushing goldfish down the toilet and getting drunk during school hours.

Although the school taught the same curriculum as similar schools in Britain, neither I nor the American guys who I teamed up with, would ever take anything of value out of those classes. At the end of the year, I had to tell Dad he was wasting his hard-earned money. With all that craziness in the classroom, it would require a super-human effort to step above that nonsense and to succeed in an exam I was not even sure I wanted to take. The burden of that responsibility was too heavy; after all, I was only 15 and my parents had not raised me to face that kind of challenge and even if they had, changing my good life in Rio de Janeiro for one in a school in the UK that would put me “in line” was a grim prospect.

Parallel to the anguish of what to do about my education and me, Mum came up with the suggestion that I should learn the guitar. As a toddler I had been promising on the flute, and if I became good with the strings, my ability could help me open the doors of popularity. There was already an excellent hand-made guitar at home; Sarah’s Del Vecchio which she never touched. For once, motherly advice turned out to be spot on and, unable to take school seriously, popular or not, I dived deeply into the instrument and turned that carved wooden box into a lifelong friend.

The private teacher was slim and his pale greasy face was covered in pimples that blended badly with his African features. He looked and dressed like a nerd, but was impressive on the guitar. He had been a rocker, but had converted to Bossa Nova fundamentalism and this was what he taught. In the beginning, I wasn’t too happy: I wanted to play like Jimi Hendrix while he only taught me the pure João Gilberto style. His homework was painful, it took a lot of effort to get my fingers to hold down the strings in spider-like positions and do those jazz chords. It was a tough learning curve, but when fluency arrived and the left hand did its thing while the right hand tapped the samba, the sweetest music came streaming out. From that moment on, I had found not only a state of mind that brought me harmony but I also found something to love. However, as the guitar took a central role in my existence, the O-levels became ever more distant.

As we only had classical music records at home, my source to the songs and to the styles I wanted to learn was the library at IBEU (Instituto Brasil-Estados Unidos, the Brazil United States Institute), located near our former flat in Copacabana. Set up to demonstrate the US was Brazil’s friend and to ensure an American cultural presence in Rio de Janeiro, the Institute’s shelves had tons of vinyl long play records, LPs, of famous and obscure Brazilian artists whom I began to like and to learn. It also had a respectable collection of international and national rock and pop titles. As those LP’s piled onto the old record player in my room, the sudden access to such a variety of music made the world begin to seem a broader place.

The IBEU was not only about accessing new musical worlds; they also had books and, therefore, the library also helped to expand my literary horizons. I had started earlier with the entire collections of Asterix and Tintin and by now I had grown out of those and had discovered Jorge Amado. My first book was “Capitães de Areia” (“Sand Captains”) about street boys in Salvador, Bahia, which had blown me away. Its pages described the intense life and the difficulties street kids in Salvador encountered due to poverty, ignorance and racial prejudice, before “New Brazil” had stepped in.

Although the entire collection of his work was available in the shelves of the library of one of Uncle Sam’s hubs, Amado was a self-proclaimed communist as most other important intellectuals of his generation were. Similarly to the Cinema Novo’s film makers, his work showed how the so-called masses were sophisticated and had rich lives when compared to the neurotic, urban, white nouveaux riches. After that first book I went on to read all his other ones, their pages were intense and filled with Brazilian sensuality. That literature had the effect of making my attention gravitate towards what happened outside the surrealism of home, religion and of school. His writing drew my attention towards the huge celebration of life in the melting pot of races and cultures that is Brazil.

Through Jorge Amado I discovered Bahia at the heart of the fascinating country my parents had moved to. It was the Mississippi Delta of the Portuguese speaking world and, with the exception of Haiti, the most African place in the world outside the actual continent. Unlike most black people in the world, the Bahianos were proud of their origins and lived accordingly, not as a political statement, but just because this is how they had always lived. Along with its best writer, that state had provided the country with its most talented musicians: Dorival Caymmi, João Gilberto, Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. The Samba was born there, as was Capoeira, the Brazilian dance-cum-martial art developed through the resistance of slaves to their destiny.

It was not only me who was fascinated with Bahia in the 1970s; the abundance of unexplored beaches and its Afro-Brazilian atmosphere transformed that part of Brazil into the ultimate destination for the nation’s hippies. There was something shining out of there that allowed people to connect with their country in a way that was more powerful and more genuine than the Californian style that the Zona Sul of Rio de Janeiro was adopting. Coincidentally, this was close to the time when the greatest Capoeira master of his days, mestre Camisa, a disciple of the great mestre Bimba, arrived from Salvador and popularized the sport in the Zona Sul. He started training a small group of capoeristas, Gato, Peixinho, Garrincha who would later become mestres themselves and who would form with him the grupo Senzala, now divided into several diferent groups, but that would come to dominate the Brazilian and the international Capoeira scene.

When boys of my generation reached puberty, after undergoing the domestic audio-visual introduction, moved on to the age-old Brazilian tradition of being initiated in sex either by a maid or by a professional. From one moment to another, it seemed that everyone except for me and my immediate circle of friends had already done it. As none of us had hot and available domésticas, the only way out were the pros. Given our budgetary limitations, all fingers pointed in the same direction: the infamous Casa Rosa, or the Pink House.

Many fathers took their sons to the important event or at least they sponsored the excursion. This was certainly not to be my case. With Dad in his mid-1970s, sex was not on the cards and it wasn’t a subject of discussion, not even in passing conversation. As far as he was concerned, licentiousness was the preserve of maids and other promiscuous favelados. I never accepted this, but I couldn’t help but inherit something of the idea that sex was intrinsically dirty and that it should be hidden away from polite society. Nevertheless, I was dying to be initiated and saved up for months, scraping together whatever I could for the big day.

Finally we thought that the day had arrived. One Saturday afternoon, my friends and I arranged to meet after lunch, but at the very last moment our trusted guide chickened out. Not only were we all pissed off, but so too was his dad. A few weeks later, we set off alone to the Casa Rosa. We did not know how to get there but when the taxi driver heard “Rua Alice”, he knew exactly the purpose of our excursion. On our way, we discussed whether we should lie and say we were seventeen instead of telling our true age: fourteen. Some of us thought this would bring more respect and would keep us from being thrown out. I was in favour of telling the truth because the lie would make us look even more retarded.

The Casa Rosa was big and seemed to have a faded grandeur. As we approached the house, we noticed a police car parked immediately outside, causing one of the guys want to give up. As we got out of the taxi and entered the building, several policemen were on their way out and greeted us with a reassuring smile. Inside, we sat around a wooden table by the improvised dance floor and waited, the silence only broken by the afternoon samba show coming out of the black and white television under the staircase. Next to the flickering set, there was a counter with two price lists: one for the drinks and another one for the “programs”.

One-by-one, the girls came down for their matinée session. They looked nowhere close to the unobtainable beauties who watered mouths on the beaches of Ipanema and Copacabana but at least they were younger and better looking than our maids. The madam pointed to us and said:

”It’s time for the children to have milk.”

They selected us, not the other way around, and took us to their rooms. When the action was about to begin, one of the guys knocked his knee against the bed, and from his reaction, we knew it had hurt: we could hear Mauricio jumping around in pain through the thin wooden walls. Meanwhile, the rest of us slipped into a silent and nervous mood without knowing what to do.

My girl was prettier, whiter, thinner and younger than the others. As she took off her clothes and lay next to me, I remembered the porn films. She talked to me and calmed me down, and I began to explore her body. Her naked flesh felt warm, tender and good. The act was as quick as it was disappointing, but I could at least count it as my initiation as a Latin Lover. I was not the first one to appear downstairs, which was a relief. After everyone had paid, we went down the hill making fun of Mauricio’s sore knee and his wounded pride.

The elected president Jânio Quadros resembled Britain’s Neville Chamberlain in appearance and in political positioning but he shared Churchill’s reputed love for the bottle. The masses adored him, but the elite ridiculed his over the top mannerisms and sneered at his mediocre intelligence. This was a time of great political turmoil with a growing influence of working class organizations on Brazilian public life, which made the middle and upper classes feel threatened. In 1961, Quadros resigned hoping the country would unite to demand his reinstatement.

This never happened and his vice president, João Goulart, took over. Goulart had strong links to trade unions and to left wing state governors, such as Miguel Arraes in Pernambuco and Leonel Brizola in Rio Grande do Sul. In contrast to the United States, Goulart saw no problem in maintaining good relations with Fidel Castro’s Cuba and he went so far as to invite Che Guevara to give a speech to the Brazilian Congress.

The Cuban revolution was still very much in the air. Confronting the political and economic control that the United States had over the region, that uprising had shown Latin America new possibilities. As far as the political left was concerned, Cuba had demonstrated that the continent had the ability to stand up for itself, choosing social justice, independence and development over the subservient path envisaged by the so-called “free world”. Societies striving towards cooperation rather than on profit scared the hell out of the establishment, especially at the height of the Cold War. Washington did everything in its power to crush the Cuban example, imposing a trade blockade, helping exiles in an aborted invasion and attempting to assassinate its leaders. The only result of this policy was to push the Cubans closer to the Soviet Union, and this alliance made a socialist – a communist even – Latin America a dreaded, but very real, possibility.

As for Brazil, the United States was determined to keep the largest country in South America “free” and in 1964 they actively supported a military coup. There were troops and tanks in the streets of the main cities, but they found no organized resistance to challenge them. Although the military leaders stated their aim was to restore democracy in Brazil by getting rid of the communists, it would take two decades for the country to return to political normality. The new regime exiled President Goulart and his allies, withdrew the political rights of numerous public and media figures, and imprisoned key leftist activists.

Despite outrage amongst the intelligentsia and at first a general indifference within the working class, the military delighted the business community, Dad included. For them, Brazil desperately needed to modernize to achieve its full economic potential: the giant had to wake up. With the business friendly, anti-communist military in power and guidance from Uncle Sam, nothing could go wrong.

*

Not until 1968 did Brazil’s civil society begin to stand up in opposition to the government, mirroring events in Paris, Chicago and Prague. After the police shot and killed a student, 100,000 people, including many eminent artists and intellectuals, took to the streets of Rio in the largest anti-government demonstration that Brazil had ever experienced. Opposition spread so fast that even military-appointed congressmen started to speak out against the undemocratic rulers. The regime’s response was swift and brutal, overruling the constitution to issue the infamous AI-5 – Unconstitutional Act Number Five – suspending congress and handing full political authority to the president. Members of the opposition, protest leaders and journalists were imprisoned. Torture became commonplace and many leftist politicians, writers and artists fled into exile.

Some students went underground and joined urban guerrilla organisations, staging successful bank robberies and high-profile kidnappings. In 1969, after the seizure of the American ambassador in Rio and the planting of bombs in military quarters, the authorities stepped up the repression. People started to disappear, including the son of our family doctor. Embryonic nuclei of revolutionary militias took to the countryside seeking to emulate the Cuban revolution. In one case, in the early 1970s, the Brazilian army dispatched a division of around 10,000 soldiers to hunt down some twenty Maoist youths in the remote Araguaia jungle region. The army executed most of the captured militants.

These were dark times and the authorities censured everything; books, plays, films, songs. They also kept a tight grip on the content of all newspapers and of all radio and television stations. Nevertheless, although the violent suppression of the Araguaia insurgency went unreported, people sensed the tension and the militants acquired a legendary status. There were all sorts of crazy theories about the reach of the guerrillas’ power. Like with anything else in life, when myth takes over problems emerge. In this case, both the militants and their suppressors overestimated what minute groups of extremists could possibly achieve in such a vast and complex country. Together, the opposing sides sent the country into a steady political decline. There was fear and mistrust everywhere, and sometimes my pre-adolescent friends and I would interrupt voicing our political fantasies when we saw someone suspicious around. At night in bed, listening to underground rock ‘n’ roll music and feeling oppressed by my parents; I transformed into a secret revolutionary, dreaming about taking up arms to fight for liberty and equality.

*

The brew of repression, rebellion and revolution on one side and the collapse of traditions, the new technologies, free sex and forbidden drugs on the other, affected everyone in one way or another, and resulted in a polarized society. A young person had to choose between being an agent of change or a supporter of the regime.

However, with the impossibility of political solutions, counterculture emerged as a tolerated middle ground. The subversive germ was kept alive in non-mainstream artistic expressions generating the famous slogan of “be a marginal, be a hero!” These anti-establishment devotees also wanted to change the world, but they did not belong to any left-wing organization aiming at regime change. This allowed them to voice the spirit of change and, because the system was able to dismiss their artistic creations as mere entertainment, record companies and other entrepreneurs were free to exploit these expressions as a lucrative, rich kid’s market. Although neither side liked each other, there was an explosion of talent backed by solid marketing strategies in what was one of Brazil’s most creative cultural periods.

On the other hand, if censorship had managed to mute local expressions it could not interfere with Brazil’s educated youth having access to foreign voices at a time when anti-establishment culture was at its peak abroad. Any Brazilian who had a dictionary around or who knew English, could easily connect to what was going on in the minds of their counterparts abroad. The loudest voice in counter culture was music, more specifically in Rock ‘n’ roll that still had plenty of revolutionary influence in it.

What may be hard to understand in today’s cynical world is that everyone – even the members of the greatest bands – believed in the changes they defended. Fame and fortune were not the only motors that drove the great rockers at their peak, they genuinely saw their creative outputs as being part of a wider movement to overthrow the political and social status quo. The technological edge of their music helped deepen its rupture with the past, and was celebrated with ecstatic solos on their distorted guitars, which gave a sound and even a spiritual edge to the dream.

This was my musical upbringing. I was eight when the Beatles split up; Led Zeppelin released “Stairway to Heaven” when I was nine; the Rolling Stones launched “Exile on Main Street” when I was ten; and Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of The Moon” was released when I was eleven. For someone from a traditional Jewish background living under a military dicatorship these were ground-breaking and mind-blowing cultural torpedoes and their energy guided my generation throughout its formative years. Although the outcome of most these bands were commercial triumphs, they were much more than this; their music separated the new from the old. By listening to them, and by adopting their attitude, young people suddenly became closer to each other, sometimes closer to “subversive” strangers than to their own family.

We, from the youngest generations, received these messages in our remote bedroom outposts – we had to resist the “squares” and fight to be ourselves, to create our own identities, and subvert the plans that the system had in store for us and for the future. The military noticed the agitation and knew that there was something uncontrollable in the air, but they could not put their finger on it, let alone halt it. They could imprison a hippy for smoking weed, but not for his thoughts.

This radical, libertarian, perhaps distorted and somewhat naive struggle consuming the youth would have more complicated consequences as it sank deeper into the social fabric. The consumption of drugs exploded in the favelas and crime became more frequent and more daring. In fact, the Brazilian organized underworld was born around this time, when in the 1970s, political detainees were confined together with some of the country’s most dangerous criminals in the high security prison of Ilha Grande, to the south of Rio. The militants viewed their cellmates’ fate as a consequence of a flawed economic system, and to move the revolution forward they sought to convert the so-called “common criminals” to their radical views. While it is doubtful that this campaign of politicisation was at all successful, the criminals did take on board the importance of group solidarity and of structure. With this in mind, they began a syndicate that operated outside the penitentiary system but that was controlled from inside the prison walls. They put in practice the techniques the militants had taught them and became competent bank robbers and kidnappers. This was the birth of the infamous Comando Vermelho (the Red Command) that would become Rio’s most powerful underworld organization, controlling most of the city’s drugs and arms trafficking.

The Clube de Regatas do Flamengo was one of several of upper middle class clubs clustered next to some of Rio’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The Flamengo club, home to the world-famous football team of the same name, was on the shores of the filthy waters of Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas (Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon), near our own Clube Paissandu as well as near to the Clube dos Caiçaras, the Clube Monte Líbano, the Associação Atlética Banco do Brasil, the Clube Piraquê, the Clube Militar, the Jockey Club and the Equestrian Club, or, as it was usually called, the Hípica.The Flamengo’s grounds were the largest of all the clubs and it was the easiest to join. Perhaps because of its size, the Flamengo was the only one to have proper sports facilities including an Olympic-sized pool, where some of Brazil’s top swimmers practiced, and where I took lessons three times a week.

After the swimming classes, I would walk to the Paissandu down the block. Despite being so close, everyone considered the walk dangerous as although this was a major route for cars, there were no shops, houses, offices, or street life, only tall concrete walls protecting the clubs. Because of this, the area was a fertile ground for assaltos, or muggings. One afternoon three favelado boys approached me, asked what I had in my bag, threw me to the ground and then ran off with my belongings. There was nothing of value – just a wet towel and my trunks – but the feeling of impotence for not being strong or courageous enough to react was traumatic. I was only twelve and when I arrived at the club house in tears, Mum’s British instinct set in and we immediately went to the local police delegacia to file a complaint. The delegacia was across the street from the Paissandu Club. The bored receptionist took us upstairs to talk to the delegado who did not even bother to move from behind his heavy metal desk. The fat, dark, moustachioed commander barely glanced at us through his sun glasses, tossing towards us some mug shots of dangerous criminals to see if I could recognize any.

The station was a yellow bunker-like construction with thick bars on its windows and had all sorts of police cars parked around it and had the insignia of Rio de Janeiro’s military police plastered over the door to make everyone take notice of the menacing importance of the building. The Fourteenth Delegacia de Polícia faced the Cruzada São Sebastião, a narrow alley that hosted the only social housing in the neighbourhood. This was by far the most dangerous place in the otherwise exclusive Ipanema and Leblon districts, somewhere we had always be warned was a complete no-go area. In fact, the Cruzada was very much like a refugee camp, its residents being the remnants of Praia do Pinto favela that until the 1960s had existed in the midst of all those exclusive clubs. Shortly after the 1964 coup, the military authorities backed its burning down after several “peaceful” attempts to remove the inhabitants. The land was conveniently freed up for friendly building contractors, and the families who then moved in were mostly of the military’s middle ranks.

The people lived on one side of the Cruzada São Sebastião in prison-like rows of eight-storey buildings. On the other side of the alley there was a tall wall, topped by a fence covered in barbed wire, which separated that silently angry enclave from our five-a-side football field. We often played at the same time as the boys on the other side of the wall. If our balls flew over, they would never come back. The same was true for their balls but, as they were better players, few landed on our side. There were occasional exchanges of rude words and stones, and sometimes more daring kids climbed up to threaten us but, in so doing, they then became easy targets for ball kicks.

Boys like those from across the alley and like my muggers worked in our club as tennis ball boys, their parents sometimes being part of the club’s under paid staff. Without exception those moleques were miles tougher and fitter than even the toughest and the fittest of us. Occasionally, we would play against them but we might as well have sat back and learned something from their genuine Brazilian footballing magic.

We feared them but, at the same time, we also secretly respected them. The truth is that every carioca male was a bit jealous of the archetypal black man, admired for being good at football, fighting and samba idealized as being supremely virile and with tons of sexy women running after him. The only desirable feature that they lacked was, of course, our white skin.

The people who we classified as favelados were the great proportion of Rio’s population, but they only emerged into our field of vision and respect either as football stars, as artists or, for some of us, as drug dealers. Otherwise, as far as we were concerned dark and poor people were servants and maids in our homes, clubs, schools and office buildings. Outside work, they were carnival dancers, beggars and muggers, people waiting to be put in prison and deserving their fate for being lazy, dishonest and libidinous. Ultimately, with the backing of the middle and upper classes, Rio’s undemocratic administration was working hard to keep the masses as far from us as possible. For them, people who had committed the crime of being born with dark skin and poor were to be no more than extras in our closeted existence, similar to how South Africa’s non-white population lived under apartheid.

In our homes, the link between the rich and poor world was embodied in our maids. Those female servants, and the attitudes to them, were remnants of the days of slavery, which in Brazil only ended in 1888 – not even seventy-five years before I was born. Every flat or house built for the lower middle class upwards had a servants’ quarters, and we all had at least one maid at home to clean, do the laundry and cook. They would labour all week doing long hours, and sleep in stuffy, windowless rooms with the sole comforts being a crucifix on the wall and a cheap radio set on top of a small cupboard. Outside their door, ironing boards, brooms and dirty clothes waited for them. The contrast with the rest of the comfortable homes where white Brazilian middle class families enjoyed their tropical paradise was staggering. This almost unnoticed element of the social gap was a constant in daily life no matter the head of the family’s profession, religious belief or political views. Leftists were no exception; their political fantasies did not inconveniently interfere with their domestic comfort. They viewed “the proletariat” as “noble savages” who they liked to imagine lived in a permanent samba party and were inherently good, just as all exploited members of the underclass surely were. But somehow the maids were just too real to be idealised, although – depending on their disposition and looks – plenty of patronizing chatter went on, as well as occasional flirtation and sexual contact.

When I was little, one of the many domesticas who passed through our lives risked her job by secretly bringing her son with her to live in the flat in weekdays. As the rigid code of conduct was concerned, this was beyond the pale. Naturally I knew nothing about such rules and I was the only one at home aware of my hidden friend who followed me everywhere but who hid behind curtains when my mum was at home. One day Mum discovered what had been going on. There was no question of tolerance: Mum fired the maid on the spot. This harsh attitude was in line with the ethics of that time and place, and it went without saying that all our neighbours and friends supported her decision.

In contrast, our last maid, Dona Isabel, stayed with us for over fifteen years. She was a Brazilian version of Mrs Two Shoes, the Tom and Jerry cartoon maid – she was pitch black, short and stocky, and had a gigantic backside above her thick and bent legs. It was common in Brazilian homes for emotional ties with the maid to develop, and certainly this was the case with Dona Isabel: my sister Sarah and I regarded her almost as family. Even so, the general acceptance of the status quo never allowed us to imagine what was passing through Dona Isabel’s mind. We will never know. All we really knew about her background was that she had grown up on a farm in the state of Minas Gerais and had a very typical accent from there, and that she found comfort in Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion. Dona Isabel was barely literate but really smart and she managed to teach herself to understand English .